The energy sector is currently undergoing the greatest revolution since the Coal Age gave way to the Oil Age. New technologies are radically transforming the economics of delivering power. Over the past decade, the cost of delivering power to people living off-grid through standalone solar and storage mini grids has decreased by up to 85%.

The World Bank believes mini grids will be the cheapest way to bring power to half a billion people, most of whom live in rural communities and would be considered low-income on any global scale. But although mini grids are already cheaper than the main grid in many areas, they are still too expensive to profitably connect these potential customers.

There is an opportunity for a new revolution in energy access. As governments consider ways to rebuild the global economy, investing in mini grids is critical to driving equitable economic growth and a climate positive future. To achieve this seismic shift, we need to unleash innovation.

Private mini grid companies are working to incrementally innovate the business model. However, it’s not happening fast enough. To speed up innovation and unlock revolutionary change, the Rockefeller Foundation seeded the Mini-Grid Innovation Lab.

A new approach to innovation

The Mini-Grid Innovation Lab is pioneering a new approach to innovation in energy access. Launched in 2018, the Lab identifies the most promising innovations by field testing prototype innovations in an iterative process and evaluating which have the greatest impact on the business model. The Lab is funded with public money and donor funds, and makes its findings public, sharing innovations directly with companies and governments to spread the knowledge.

The Lab consists of 25 private mini grid companies, working in collaboration together. It accelerates the speed of innovation by working through these 25 private actors, combining the strengths of public and private sector innovation.

Every quarter, the Lab convenes these 25 private mini grid companies to identify and design innovations to test within their own businesses and among their own customers. It then funds these private sector companies to test the innovations, on the condition they share the resulting data with the lab to distribute with the entire private sector.

The Lab aggregates the data across all companies and analyses it to determine the impact on the business model. It makes its findings publicly available, for free, to the entire sector, and continually repeats this process of idea gathering, testing, and sharing to rapidly accelerate sector innovation.

Private sector and public sector approaches to innovation

In a simple model, innovation can emerge in two ways:

- Private sector competition: Private actors, with strong incentives to innovate, compete in the marketplace. Take the smart phone as an example. Apple and Samsung compete through every smart phone release to deliver a better product.

- Public sector sponsorship: Public actors fund long-term research with the goal of creating public goods to be utilized by all players. In The Entrepreneurial State, the economist Mariana Mazzucato observes the origins of the key 12 technologies that made the iPhone possible – from solid state hard drives, to liquid crystal displays, to GPS, to Fast Fourier Transform Algorithm – can all be traced back to U.S. and U.K. government-funded research.

Each model involves trade-offs.

- The strength of private sector innovation is speed and relevant knowledge of the problem. Its weakness is information sharing.

Private sector companies are often the best engines of short-term innovation, because the incentive to survive is highly motivating. These companies are also the best judge of the most relevant solutions given they’re closest to the problems. However, we can’t rely on private companies to scale innovation to other companies in the sector. It’s not in their market interest to do so. In fact, it’s in their interest to stop the spread of innovation.

Apple’s seven-year pursuit of Samsung for patent violations was only settled last year for several hundred million dollars. Every smart phone is slightly more expensive and slightly lower quality than it could be, because each private sector actor is jealously guarding its competitive advantage.

An SSIR article last year raised this issue with private sector innovation in Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) solar, noting “Mutual awareness is low, and meaningful coordination is even more uncommon. This applies to collaboration…between companies and organizations working within the same sector.”

- The strength of public sector innovation is information sharing and patient funding. Its weakness is speed in bringing innovations to market.

Public sector innovation is, by definition, public. Unlike their private counterparts, public actors make their innovations widely available – they share all information for the market to act on. Public actors can also be more patient and direct large amounts of risk capital towards innovation without a return expectation.

But public actors are typically further from the problem and are also inherently less incentivized to drive toward a ‘product’ or solution that will reach the hands of a customer in need. None of the government agencies working on the technologies behind the iPhone integrated them into a commercial smartphone. Public innovation is shared but is slow and disconnected from end users’ real challenges.

Popular content

The Lab's combined approach to innovation in action

The traditional paradigm of innovation presents a choice. Fast but proprietary and therefore siloed. Or, shared but slow and isolated from the end-user. The lab is pioneering a new model that captures the best of both models. It provides donor funding to private sector actors to test agreed innovations on the condition that they share the results back with all their competitors.

Through this approach, the Lab combines the strengths of private sector innovation – speed and relevant knowledge of the problem – and public sector innovation – patient funding and open dissemination of knowledge. To make this real, it’s helpful to consider an example.

Grain milling is one of the most important productive uses of energy for people living off-grid in rural Africa. Maize is the most commonly produced cereal in sub-Saharan Africa, and grain millers use that maize to produce flour, a key ingredient in staple foods for rural communities.

Powering grain mills with solar mini grids would transform the off-grid energy sector, delivering clean, reliable, 24/7 power to rural businesses. However, diesel mills dominate the rural off-grid market, because no solar-powered electric mill exists that can match them on both cost and performance.

To solve this, the Lab brought together a coalition of private sector and public sector partners to iterate on the off-grid electric mill until it could match its diesel rival. It ran the following process:

- The Lab's community of developers agreed this was an innovation worth prototyping.

- The Lab then funded PowerGen, a private mini grid company operating in East and West Africa to procure electric mills from China based on best-in-class mill specifications developed by Factor[e] Ventures, an early stage investor in East Africa and India supported by private and public funding.

- When the mills arrived in East Africa, PowerGen additionally enlisted the expertise of Agsol, a private sector off-grid appliance manufacturer based in Nairobi, and SIDO, a Tanzanian government agency focused on promoting SMEs, to customize the mills to the local market. Together, they increased throughput by 50% by installing larger pulleys, improved efficiency by adding a switch to run the mill’s rice huller and maize grinder separately and replaced the sieves to produce the finer flour that customers want. The resulting mills are four times more efficient than diesel.

- PowerGen shared these results back with the Lab. The Lab then shared these findings with, and made the mills available to, all other developers in the community.

- All developers are, therefore, now able to adopt this innovation created by donor funding.

The Lab is now applying this innovation approach to other promising tools to drive down capital expenditure costs and drive-up revenues. It is conducting field trials deploying smart inverters, reducing electricity tariffs, bulk procuring hardware, and bundling internet with power across Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, and Zambia.

The Lab is also partnering with advocacy experts, technology companies, financiers, and on-the-ground implementing partners to scale those innovations proven successful. With Rockefeller’s support, it will share its findings with key governments, donors, and investors needed to accelerate this scale.

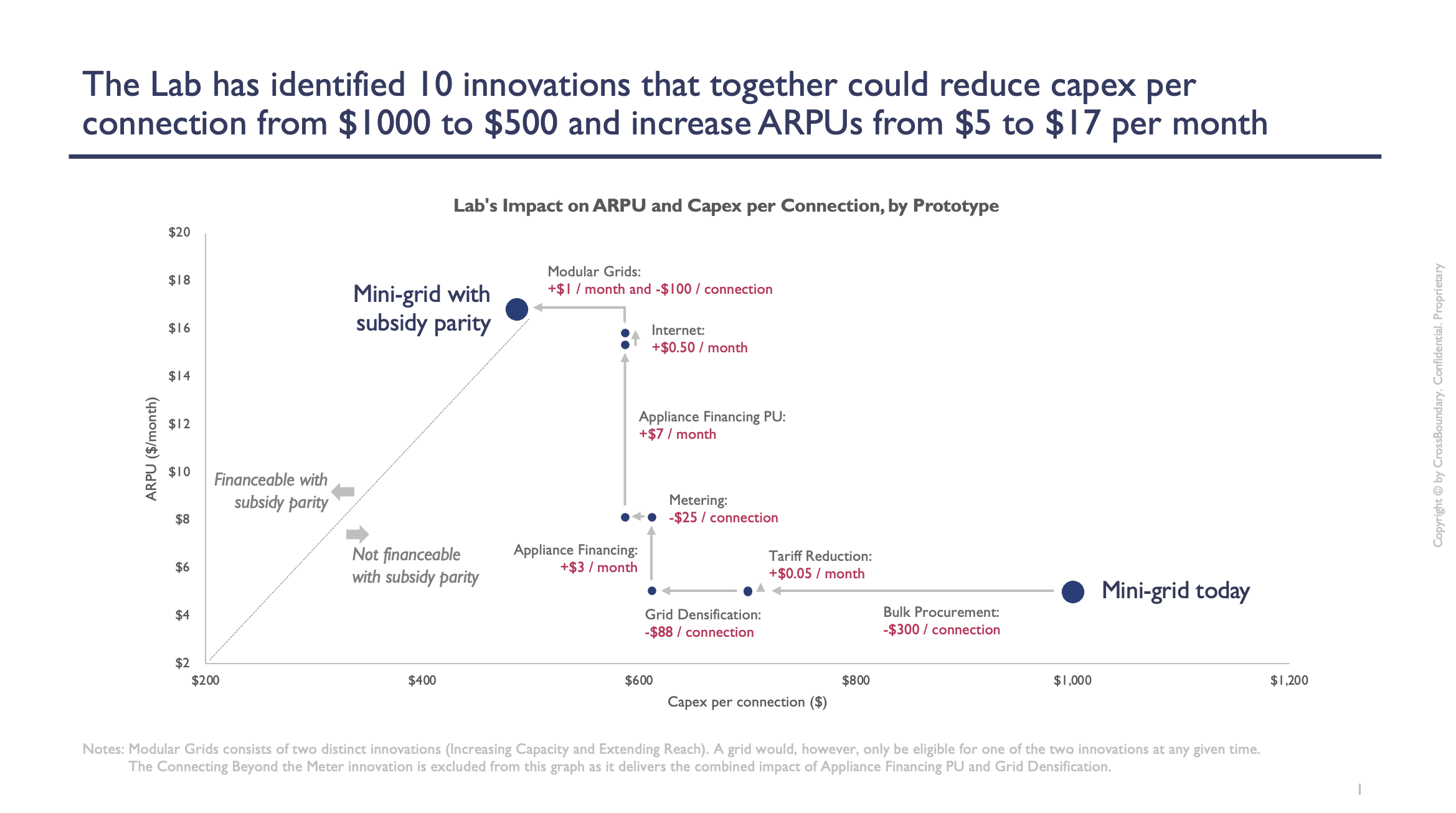

The Lab is field testing 10 innovations that together could make mini grids commercially viable by reducing capex per connection from US$1,000 to $500 and increasing average revenue per user (ARPU) from $5 to $17 per month

The Lab is field testing 10 innovations that together could make mini grids commercially viable by reducing capex per connection from US$1,000 to $500 and increasing average revenue per user (ARPU) from $5 to $17 per month

If these trials are successfully scaled, this new approach will have dramatically accelerated progress towards universal electrification in Africa. It will have sparked a new revolution in energy access, giving poor, rural communities across the continent access to affordable and reliable power for the first time.

Looking beyond energy access

We believe the Lab represents an interesting new model of innovation that combines the strengths of both private and public sector innovation. This approach could have a similar impact in other sectors where advancing public good requires private sector innovation.

Donors could support innovation Labs in smallholder farming, microfinance, and transport. Combining the speed and relevance of private sector innovation with the broad dissemination and funding of public sector innovation offers a way to ‘innovate on innovation’.

About the authors

Erika Lovin leads the Lab and is an associate principal at CrossBoundary, Gabriel Davies is the head of CrossBoundary Energy Access, Matt Tilleard is the co-founder and managing partner at CrossBoundary, and Suman Sureshbabu is a director of the Power & Climate Initiative at The Rockefeller Foundation.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.