From pv magazine USA

Working with Evergy, a utility serving customers in Kansas and Missouri, the Kansas Geological Survey is studying the possibility of storing excess energy generated by coal-fired power plants in underground salt caverns for future use.

“Excess electricity can be used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen gas,” said Franek Hasiuk, KGS geologist and principal investigator for the project. “The hydrogen can then be stored in salt caverns for later use, either by burning it with natural gas in the power plant, adding it into pipeline natural gas for burning in home furnaces and stoves, supplying it to another business for use in chemical processes like fertilizer production, or using it to power vehicles.”

As electrical grid operators increasingly buy power first from wind, solar and nuclear operations and turn to natural gas and coal plants only when needed, there’s a growing need for storage of energy for future use.

“Hydrogen storage could allow Evergy to store large amounts of energy to deal with the problem of intermittent power production from renewables – no solar when it’s night, no wind power when it’s not windy,” Hasiuk said.

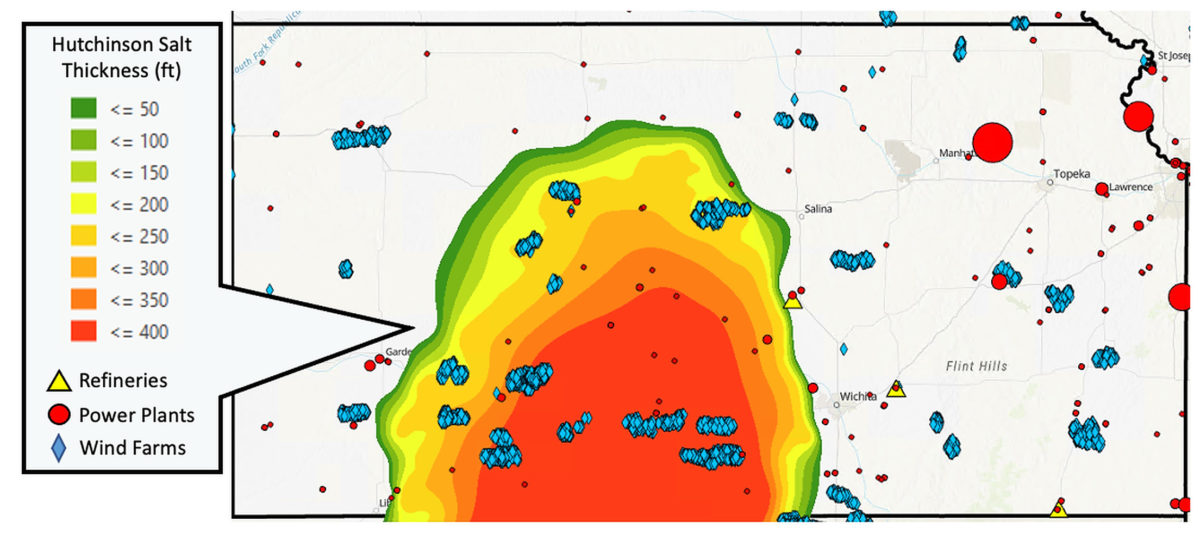

Extensive salt beds lie under the surface in Kansas. The Hutchinson Salt Member, deposited during the Permian Period, covers about 37,000 square miles in the subsurface in central and south-central Kansas and reaches a maximum thickness of more than 500 feet. Thick salt layers also occur in western and southwestern Kansas.

Popular content

Salt has been mined in Kansas since the late 1800s. Caverns in the salt beds are used for storing natural gas, natural gas liquids and other hydrocarbons.

The study, supported by a $200,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, will study the economic risks and benefits of storing hydrogen in these underground salt caverns.

“Right now, it’s unclear whether undertaking a project like this is feasible for energy companies,” Hasiuk said. “Our study will help reduce the uncertainties related to hydrogen storage. At the end of the study, we may find out the costs of underground storage are as risky as or more risky than thought, but we should certainly be more confident about just how risky it is.”

If the one-year project successfully demonstrates the viability of hydrogen storage, the partners will move to a second phase consisting of more advanced engineering and design of a storage system.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.