CRE4 was expected to be a turning point for the French solar industry by giving developers medium-term visibility on the periodicity and volumes called through tenders and by initiating a shift towards a market oriented business model, through the feed-in premium mechanism (known in France as “Complément de Rémunération”).

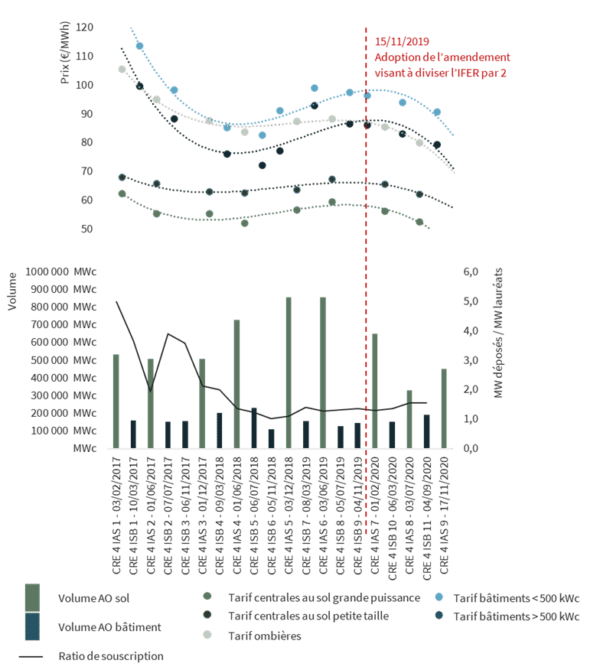

Looking back over the past four years, a significant drop in tariffs has been observed. Large-scale ground-mounted projects went from €62.5/MWh in March 2017 to €53.4/MWh in February 2021, i.e., an around 15% drop over four years, or 3.9% per year (and notably -5.1%/year for the “large rooftops” category).

Despite the general tendency, tariffs for all categories followed a sinusoidal curve: an initial drop, due to very large candidate volumes and increased competition because developers accumulated large pipelines of projects in anticipation of the CRE4 launch. This was followed by an increase when project pipelines dried up somewhat (some tender sessions were undersubscribed compared to the initial target volumes, particularly for rooftops).

This increase was seen by some as a return to reason following the first period of decline which caused some concerns about the winners’ ability to finance and build the projects. A second period was then observed towards the latter years of CRE4, for which the announcement of the IFER reduction for commissioned projects after January 1, 2021, seems to be the main explanation.

CRE4 has, thus, confirmed the ability of solar energy to provide competitive energy, especially from large-scale ground-mounted plants. Price competitiveness of projects in CRE4 can be appreciated by comparing them to the Hinkley Point remuneration set at GBP 92.50/MWh, or to the wholesale price of electricity observed on the French market in 2020, which is around €42/MWh on average.

A framework for trust and investment

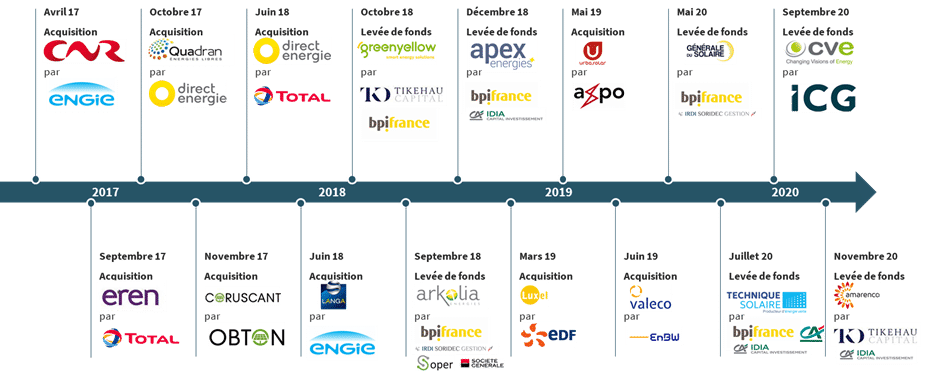

The CRE4 program was marked by a strong wave of consolidation led by energy companies and utility majors – both French and foreign – which played a crucial role in the dynamics described above. Foreign entrants will no doubt have been attracted by a French renewables market that has now reached a significant size in the broader context where renewables are increasingly difficult to ignore.

On the other hand, the visibility over future volumes has allowed many developers to implement their development strategy over the medium- to long-term and to engage in significant investment and growth dynamics by carrying out capital increases.

These transactions have mainly been subscribed to by institutional investors or specialized investment funds, which were previously attracted by direct investments in infrastructure assets but are now looking for higher returns, by investing in developers/producers to move up the value chain and thus to improve their yield prospects.

Finally, throughout these tenders, new French and foreign developers have appeared after deciding to enter the market, no doubt attracted by the stable prospects of the support framework. The French market now seems to be more structured and undoubtedly better able to achieve the objectives of the PPE.

CRE4 also provided the opportunity to increase capital deployment into the green economy. Some asset managers created dedicated investment vehicles to address the energy transition market, and those that were already there raised even larger funds that can address more complex markets.

In addition to the consolidation process described above, Finergreen witnessed numerous transactions involving the partial sale of operational portfolios that had reached a critical size, to financial players looking for a stable and secure investment return over the long term. Examples include Caisse des Dépôts' investment in the Tenergie vehicle in 2020, or Predica's investment in the Engie or Total Quadran vehicles in 2021.

The banks, for their part, have played a major role in accelerating the development of the sector by financing projects on increasingly attractive terms. The challenge of integrating solar energy into a market economy via the Complément de Rémunération has finally (and rightly) been resolved without real complexity, giving utilities the opportunity to play the role of aggregators without any impact on bank financing conditions.

These conditions were even significantly improved during this period, with the structuring of financing tenors longer than the duration of the feed-in tariff/premium. This period saw players become increasingly financially sophisticated. The use of various debt products to finance their growth (senior project financing, junior debt, revolving credit, the emergence of Green Bonds, etc.) has enabled developers to innovate and constantly find ways to improve their competitiveness.

The robustness of the sector during a crisis such as Covid-19 is only likely to attract even more capital, and the stock market performance of the French listed players seems to testify to the confidence and interest of investors in the green economy that is increasingly favored by the institutional and political spheres.

Popular content

A transition to market models is underway

The integration of renewable electricity into a market economy was one of the objectives of CRE4. From this point of view, the Complément de Rémunération mechanism will have responded positively to the challenges it faced. However, the transition has only just begun and much remains to be done.

Today, through the CRE's tenders, players have a robust and proven business model that is bankable. As long as these tenders offer sufficient market depth – both in terms of volumes and constraints – the interest in turning to private PPA-type solutions will probably remain limited.

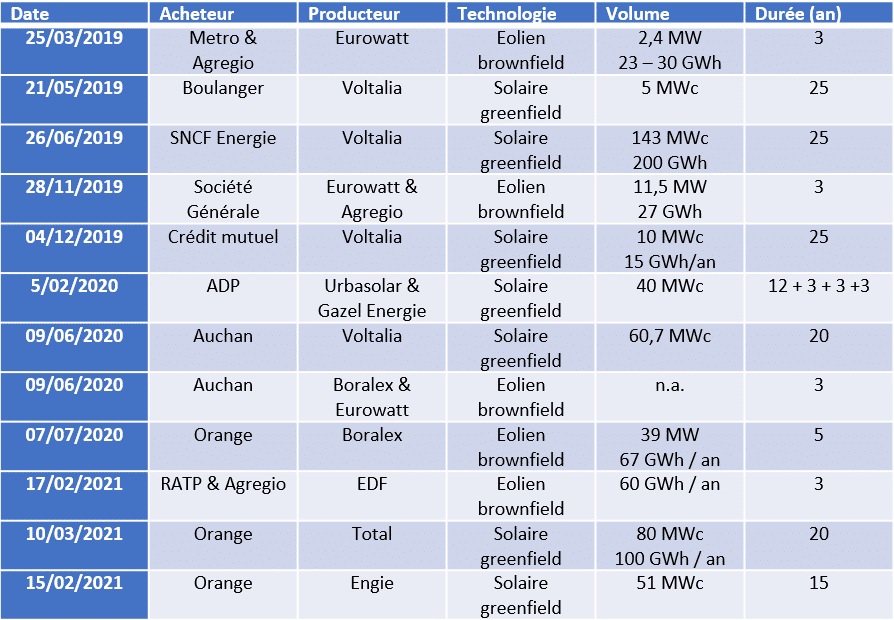

These projects require a more complex structuring and, therefore, more constrained financing (ad-hoc terms and conditions of the negotiated PPA, credit quality of the counter-party, direct exposure to the underlying electricity price, etc.) even though a few symbolic transactions have been carried out in recent months, often justified by (i) the desire to secure a purchase price over a short period of time for assets coming out of the feed in tariff (known as Obligation d’Achat), or (ii) by long-term visions of developing assets not eligible for the tenders while carrying out important CSR communication operations.

While it is likely that participating in the PPE2/CRE5 sessions and obtaining a secured feed-in premium will continue to be a preferred solution for solar PV project developers over the next few years, it is nonetheless clear that an ever-increasing shift towards private PPAs should be anticipated, for several reasons:

- The perspectives of increasing electricity prices, coupled with a strong desire to carry out “green” operations, are leading corporates with a significant electricity bill to investigate ways to optimize their supply, with solar energy being a competitive energy which also enables them to achieve their CSR objectives and to communicate around it;

- Developers will look to set their long-term strategy, beyond just the future CRE5 program, and must anticipate the future market shift to develop the skills internally or to integrate external human resources to best succeed during this transition in the coming years; and

- It is very likely that the constraints linked to the tenders – mainly typology of land, origin of the panels – will be renewed in CRE5 and that project developers will identify a significant growth opportunity in private PPAs, which should enable them to get more MWs out of the door quickly with fewer development and calendar constraints (no tenders to prepare).

All these positive factors in the development of the private PPA market remain, however, subject to the obvious question of the financial feasibility (and therefore ultimate profitability) of PPA projects.

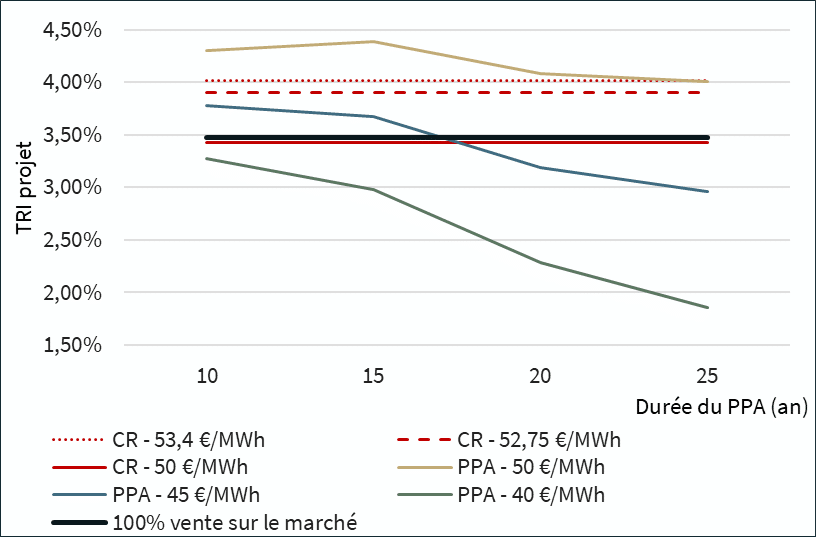

Assuming that a PPA project will save on CAPEX (mainly due to cheaper PV panels) and on OPEX (less competition on land and rents), we observe for a single 50 MW plant the following project IRRs (i.e., before financing) based on a 30-year operating life and a solar captured central merchant curve:

(Notes: CR = remuneration supplement; 53.4 €/MWh corresponds to the average tariff obtained during the last call for tenders, 52.75 €/MWh on average over the previous round; PPA prices are not indexed to inflation)

Based on these assumptions, it is interesting to observe:

- That the project IRR obtained through a €45/MWh PPA signed over a 16-17 year period is similar to the one obtained via a feed-in premium of €50/MWh over 20 years.

- Based on current electricity price projections, the project IRR of a power plant selling its electricity on the spot market is similar to the one obtained via a CfD of €50/MWh over 20 years.

- In view of the upward trend in electricity prices, it now seems more strategic to sign PPAs with a duration of approximately 15 years, to benefit from high spot prices in 15 years and more.

We can therefore see that a PPA at €45/MWh, which can be considered in the money when looking at the average electricity prices over 2020 at €42/MWh (with an upward trend), has an intrinsic profitability roughly equivalent to current feed-in premium projects. It is therefore crucial to improve the solutions and vision of long-term financing for PPA projects, as the issue of financing seems to be the last barrier for the accelerated development of PPA projects.

The rest of the story is, thus, partly up to the financiers, who will have to innovate and provide new financing approaches that are more flexible or accommodate better the uncertainty associated with these new models. Even greater attention will have to be paid to the underlying electricity market because it is not only a counter-party risk that will have to be controlled, but also ,and above all, a risk linked to the fundamentals of the market. As a counter-party defaults, financiers will have to ensure that there is a solid market outlet over the duration of the financing period and a sufficient pool of potential off-takers who will be interested in re-contracting with the producer.

Finally, more uncertainty implies more risk but also more profitability. Developer-producers will have to consider less optimized financing structures in their investment decisions and probably commit more equity (it could mean considering later refinancing scenarios and renewing PPAs at higher values) to justify attractive target returns. This could also have the medium-term effect of increasing the profitability of developers and “winning” projects, breathing new life into a sector with historically low returns.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.