From pv magazine 09/2021

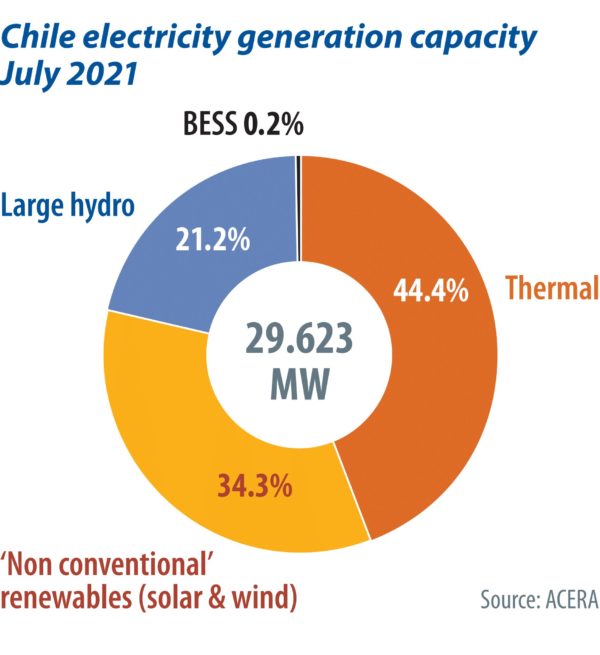

Chile’s constitution is undergoing reform, and the government is already on its way out. There has also been an extreme and extended drought that has been punishing the country for more than a decade and stressing the energy grid. Chile’s electricity network is normally 30% to 40% reliant on hydropower generation, but these days it can only produce close to 20% this way.

The first signs of alarm emerged with the Chilean protests in October 2019. Shortly thereafter came the pandemic, although Chile has been affected to a far lesser degree than many of its neighbors. Carlos Cabrera, president of Chilean Solar Energy Association ACESOL, suggests that things are already going back to “normal” in terms of demand for new installations. However, as Chile’s grids become more congested, particularly in the northern regions that host the most solar PV capacity, this may not be the most important variable.

“Putting together all the technologies, we have an installed capacity of nearly 28 GW for a maximum demand of more than 11 GW. In other words, we have nearly three times what we consume,” says Ramón Galaz, executive director of Chilean consultancy Valgesta. “This will need to be adjusted along with the decarbonization process, which needs to be accompanied by an excellent transmission system to the areas of consumption, and that is where we are falling behind. It is the most important variable,” he adds, agreeing with Cabrera, who points out that “the distributors and transmitters are being overwhelmed.”

Storage and transmission

Chile is a global leader with an aggressive decarbonization program that targets the complete elimination of carbon emissions by 2040. But some are even thinking of accelerating it. “Our honorable deputies intend to accelerate the plan and are promoting a law to eliminate all coal generation by 2025. In terms of investments, 2025 is right around the corner,” points out Cabrera, who is calling for a “more cautious” decarbonization scenario that aims for 2030.

Galaz shares this commitment to responsibility. “Coal represents 18% of Chile’s energy supply and an accelerated process can jeopardize the decarbonization process,” he says.

Chile had to recommission one of the decommissioned fossil fuel generators at the beginning of August due to the severity of the drought. “This sends an incorrect and confusing message,” says Galaz, who believes that 2030 and even 2035 are more reasonable dates to target. “We must ensure transmission infrastructure to relieve the system bottleneck, in order to make it feasible.”

For his part, the representative of ACESOL notes that Chile has 6 GW of renewable energy projects under construction, a number that he deems “stratospheric” for a 24 GW energy grid. He notes in reference to storage, transmission, and the lack of PPAs that “25% of the grid is under construction, but there are a lot of problems with putting it into service.”

Both experts agree that energy storage is a key element for decarbonization, although the road ahead seems difficult. “Excuse the paradox, but to prevent the lines from being overburdened, we would need to receive solar energy at night,” says Cabrera, unafraid of being self critical. “At the national level, regulatory signals regarding storage have been unclear and difficult to explain to investors.”

Modernizing DG

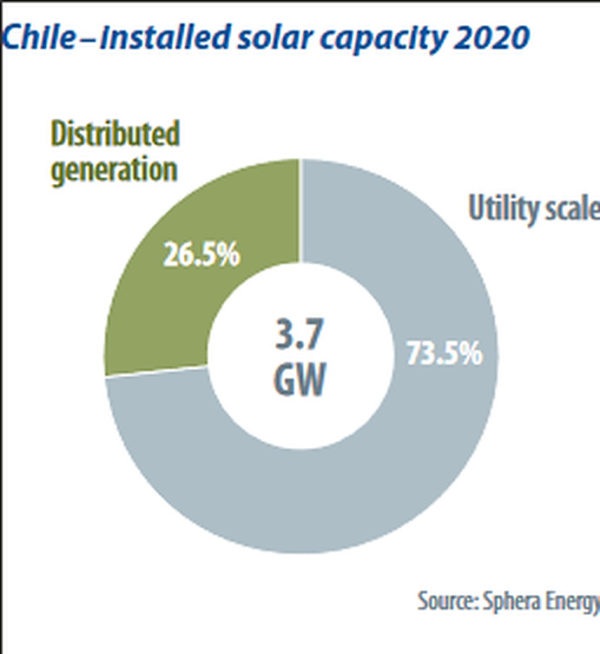

What is known as net metering in Chile – self-consumption projects that are less than 300 kW – represents 90 MW of current installed capacity, according to Cabrera. “The distributed-generation sector is far exceeding expectations. This industry has exceeded the gigawatt mark, and if today we have close to 4 GW from solar alone, 1 GW comes from distributed-generation projects, a figure that we deem spectacular. [And] 25% of all of Chile’s solar energy is distributed,” he says.

However, the DG segment is held back by the lack of a national strategy that allows for quantification of the contributions that small and medium-scale projects can make toward the carbon-neutrality goals that Chile is pursuing. In that regard, the government is still relying on larger-scale projects such as Kimal-Lo Aguirre – a 1,500-km, high-voltage interconnection cable that will connect a substation in the far north with one further south to relieve congestion – with less emphasis and promotion of smaller-scale energy projects.

In 1982, Chile was one of the first countries to privatize its energy sector, tackle deregulation, and separate generation, transmission, and distribution. Cabrera remembers that over the past 40 years, there have been modifications to generation and transmission, laws were passed, regulations were created. But the distribution industry has remained virtually untouched. “They have the same rules and logic that they did 40 years ago,” he points out. “The distribution industry is crying for modernization.”

The government announced a major reform project for the distribution system that consisted of three bills to modernize and perfect the sale of energy on the distribution side, improve standards for distribution networks, and lastly, a bill to incentivize and develop distributed energy infrastructure. However, the bill to improve energy sales is still bogged down in discussion in Congress and has not progressed. It now appears highly unlikely that the government will manage to progress with the other two bills.

Many projects, few PPAs

Chile has begun a call for tenders for 2,310 GWh/year, for which results had not been published at the time of writing. However, Cabrera believes that there is still too little energy capacity on offer, and too many providers.

“We are in a situation where we have many environmentally approved projects ready to be implemented, but they lack the PPA,” he explains. “The energy business is a combination of price and quantity; how much energy is produced, but at what price. In the north, there is so much solar energy to inject, and without transmission, there can be hours during the day where the marginal cost is zero. And this threat is always present.”

Exporters with no connection

The Atacama Desert is full of infrastructure; solar installations, desalination plants, mining, and much else besides. There is no citizen resistance there. There is practically unlimited potential for generating energy in what is the planet’s sunniest area, and Chile could even better take advantage of this with more interconnections to its neighbors. “It is feasible, recommended, and convenient,” Galaz categorically states. “Chile has a tremendous opportunity to move toward interconnection. It will not be able to absorb its production with its internal demand alone.”

Cabrera, however, takes a less optimistic look at this dream.

“The problem is: How do we send all this energy to the consumption centers? The international dream is reasonable and competitive in theory, but experience shows that it is very difficult to come to an agreement with neighboring countries.”

Hydrogen, a love-hate story

At the beginning of the legislative term, the government opted to become a major exporter of hydrogen at up to $30 billion a year by 2050 – the same amount that the country earns from its copper exports. Nowadays, enthusiasm appears to be waning.

Popular content

Cabrera describes green hydrogen as a love-hate story. “We believe that it is the fuel of the future, but we should worry about other things from now until 2030 and after 2050,” he explains. “Our geographic location is not the best, and transportation costs are very important. The Australians, along with the Germans, are strong competitors. It means that the renewable energy must be very affordable.”

Galaz adds the cost of the technology to the list of obstacles in the way of hydrogen. “Electrolyzers are expensive and have highly flammable chemical characteristics that require very high-quality standards. It is difficult to forecast the actual potential,” he indicates.

Chile will have a new president in December. “We have lost a certain sense of regulatory stability. The next government will have to work to dispel this doubt. We need judicial and regulatory certainty that sends the right messages to investors,” points out Ramón Galaz, who, despite being very critical of the errors, wishes to send a message of reassurance.

“There are tons of pending issues that we need to work out,” stresses Cabrera. “Investors are ‘quietly worried’ about what will happen in Chile over the next five, 10 years. However, there is confidence in the long-term policies that the Chilean energy industry has advanced over the past few decades.” All that’s left is to await the election results.

| Technology | Under construction | Approved | In qualification |

| Battery storage | 113 | – | 42 |

| Biogas | – | 14 | – |

| Biomass | 166 | 165 | 352 |

| Wind | 926 | 4,316 | 6,511 |

| Geothermal | – | 70 | – |

| Pumped hydro | – | 300 | – |

| Small hydro (run of river) | 57 | 278 | 58 |

| Solar PV | 3,359 | 17,441 | 11,178 |

| Solar Thermal | – | 2,192 | 840 |

| Total | 4,621 | 24,777 | 18,980 |

Modernizing DG

What is known as net metering in Chile – self-consumption projects that are less than 300 kW – represents 900 MW of current installed capacity, according to Cabrera. “The distributed-generation sector is far exceeding expectations. This industry has exceeded the gigawatt mark, and if today we have close to 4 GW from solar alone, 1 GW comes from distributed-generation projects, a figure that we deem spectacular. [And] 25% of all of Chile’s solar energy is distributed,” he says.

However, the DG segment is held back by the lack of a national strategy that allows for quantification of the contributions that small and medium-scale projects can make toward the carbon-neutrality goals that Chile is pursuing. In that regard, the government is still relying on larger-scale projects such as Kimal-Lo Aguirre – a 1,500-km, high-voltage interconnection cable that will connect a substation in the far north with one further south to relieve congestion – with less emphasis and promotion of smaller-scale energy projects.

In 1982, Chile was one of the first countries to privatize its energy sector, tackle deregulation, and separate generation, transmission, and distribution. Cabrera remembers that over the past 40 years, there have been modifications to generation and transmission, laws were passed, regulations were created. But the distribution industry has remained virtually untouched. “They have the same rules and logic that they did 40 years ago,” he points out. “The distribution industry is crying for modernization.”

The government announced a major reform project for the distribution system that consisted of three bills to modernize and perfect the sale of energy on the distribution side, improve standards for distribution networks, and lastly, a bill to incentivize and develop distributed energy infrastructure. However, the bill to improve energy sales is still bogged down in discussion in Congress and has not progressed. It now appears highly unlikely that the government will manage to progress with the other two bills.

Many projects, few PPAs

Chile has begun a call for tenders for 2,310 GWh/year, for which results had not been published at the time of writing. However, Cabrera believes that there is still too little energy capacity on offer, and too many providers.

“We are in a situation where we have many environmentally approved projects ready to be implemented, but they lack the PPA,” he explains. “The energy business is a combination of price and quantity; how much energy is produced, but at what price. In the north, there is so much solar energy to inject, and without transmission, there can be hours during the day where the marginal cost is zero. And this threat is always present.”

Exporters with no connection

The Atacama Desert is full of infrastructure; solar installations, desalination plants, mining, and much else besides. There is no citizen resistance there. There is practically unlimited potential for generating energy in what is the planet’s sunniest area, and Chile could even better take advantage of this with more interconnections to its neighbors. “It is feasible, recommended, and convenient,” Galaz categorically states. “Chile has a tremendous opportunity to move toward interconnection. It will not be able to absorb its production with its internal demand alone.”

Cabrera, however, takes a less optimistic look at this dream.

“The problem is: How do we send all this energy to the consumption centers? The international dream is reasonable and competitive in theory, but experience shows that it is very difficult to come to an agreement with neighboring countries.”

Hydrogen, a love-hate story

At the beginning of the legislative term, the government opted to become a major exporter of hydrogen at up to $30 billion a year by 2050 – the same amount that the country earns from its copper exports. Nowadays, enthusiasm appears to be waning.

Cabrera describes green hydrogen as a love-hate story. “We believe that it is the fuel of the future, but we should worry about other things from now until 2030 and after 2050,” he explains. “Our geographic location is not the best, and transportation costs are very important. The Australians, along with the Germans, are strong competitors. It means that the renewable energy must be very affordable.”

Galaz adds the cost of the technology to the list of obstacles in the way of hydrogen. “Electrolyzers are expensive and have highly flammable chemical characteristics that require very high-quality standards. It is difficult to forecast the actual potential,” he indicates.

Chile will have a new president in December. “We have lost a certain sense of regulatory stability. The next government will have to work to dispel this doubt. We need judicial and regulatory certainty that sends the right messages to investors,” points out Ramón Galaz, who, despite being very critical of the errors, wishes to send a message of reassurance.

“There are tons of pending issues that we need to work out,” stresses Cabrera. “Investors are ‘quietly worried’ about what will happen in Chile over the next five, 10 years. However, there is confidence in the long-term policies that the Chilean energy industry has advanced over the past few decades.” All that’s left is to await the election results.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

How was it possible to write this article without mentioning, even once, “lithium” and only once “copper”?