Although they have garnered much attention over the past decade, the commercial proliferation of organic polymer solar cells (PSCs) has been halted by expensive raw materials, longevity issues and lower power conversion efficiency compared to inorganic solar cells. However, their light weight, transparency, flexibility and roll-to-roll production capability suggest they may find potential niche market opportunities.

While this emerging technology is unlikely to replace traditional inorganic solar cells, a new research paper titled, Polymer solar cells: P3HT:PCBM and beyond points to a number of additional applications of PSCs, reviewing the latest advances and remaining challenges in the field.

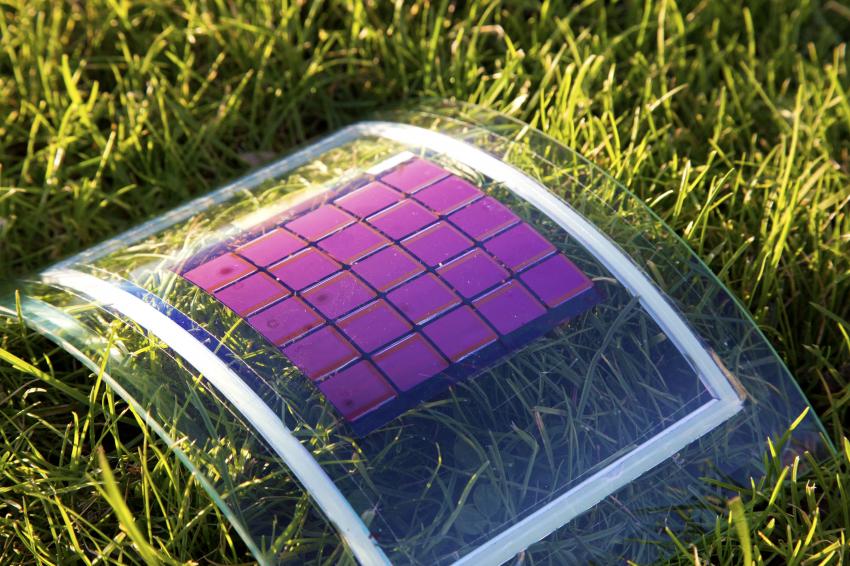

“PSCs have this ability to be flexible, because they basically are plastics, so you can put them on backpacks, jackets and even coffee creamer — a whole range of things where it's at the point of use,” said Paul Berger of Ohio State University, one of the authors of the report published in Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy. “It's a disruptive business model.”

Relying on organic polymers to absorb light and convert it into electricity, PSCs can bypass high-voltage transmission lines and provide electricity to point-of-use devices that would otherwise require toxic batteries.

For example, PSCs could power freshness sensors on food packaging simply using the overhead lights in grocery stores. Furthermore, they could go beyond store inventory control, and tie into a “smart kitchen” to reduce food waste and automate grocery lists.

The polymers can be dissolved in solvents and printed onto a flexible backing using affordable roll-to-roll production, which makes this technology especially attractive.

Popular content

“This printing press is not unlike the one for printing your Sunday newspaper, but instead of three primary colors and black, you're printing the four or five different layers needed for the solar cell, diodes and transistors,” Berger explains.

Long rolls of solar cells also allow for other innovative applications, such as wrapping vehicles or covering building facades and windows. However, according to Berger, certain expensive PSC raw materials, namely indium tin oxide and fullerenes, which have proved challenging to replace, may limit near-term affordability.

Longevity is another issue plaguing the PSC technology, because the polymers and reactive metal cathodes oxidize when exposed to water and oxygen. The PSCs can be encapsulated and thus protected from the quick degradation, but while this process can be very effective on glass, it is more challenging on flexible surfaces.

In the lab, PSC efficiency reaches about 13%, which is far below the 20% efficiency of commercial solar panels. PSCs that use P3HT:PCBM polymers, introduced in 2002, yield about 3.5% efficiency. However, recent advances in chemistry, geometry, and the development of tandem solar cells that stack multiple layers together have made this greater efficiency possible.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.