Earlier this month, India’s Directorate General of Trade Remedies (DGTR) recommended imposing a safeguard duty on imports of “solar cells whether or not assembled in modules or panels” from China and Malaysia, among other developed countries, over a two-year period, starting at 25% in year one. A duty of 20% will be imposed in the first six months in year two, and 15% for the rest of the year.

This recommendation needs to be reviewed by a committee formed by the Department of Energy and Ministry of Commerce and Industry, where a decision will be made on whether to implement, or adjust, this recommendation. Once the decision has been taken, it will be sent to the Ministry of Finance for approval.

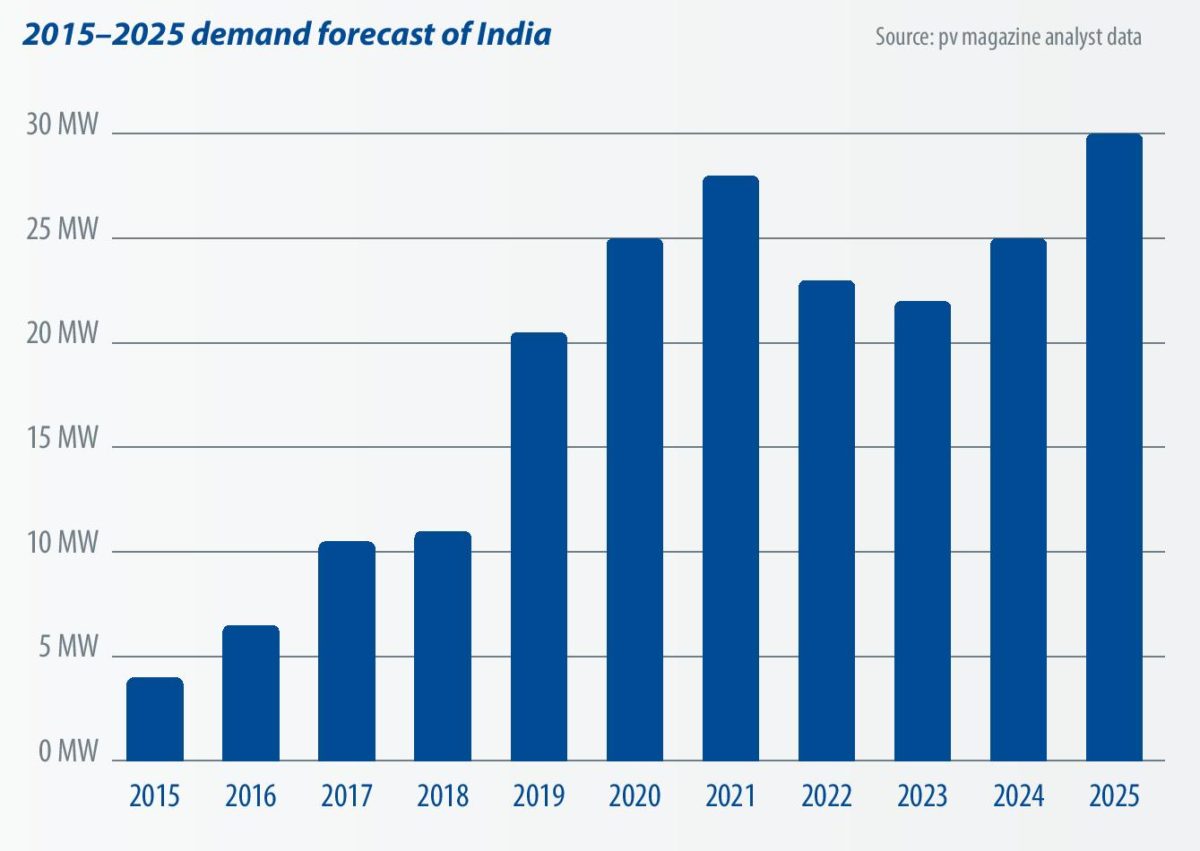

India still aims to achieve a PV installation capacity of 100 GW by 2022, and this has sparked arguments from Indian manufacturers and PV project developers on whether to impose the duty, because the domestic PV demand is currently undersupplied.

Imbalance

Image: pv magazine

Last year, India’s PV installations amounted to between 10 and 11 GW, and this year’s number was originally expected to increase. However, with numerous trade war investigations taking place since last year, India’s module demand in 2018 may decrease to as low as 9-11 GW. Looking at module suppliers, China has been the country’s largest module supplier, shipping over 9 GW of modules to India in 2017 – or around 90% of India’s module imports.

However, so far this year, China’s module export to India has largely decreased, due to concerns about the trade war. Even during the typical high season of India in Q1, China only shipped 2.4 GW of modules and 0.4 GW of cells. In addition, the slow progress of India’s projects has resulted in just 3.1 GW of modules shipped to India between this January and May. This is a 33% decrease, compared to the same period in 2017, and is fast becoming one of the major factors for causing an imbalance in the 2018 PV market.

India currently has a module capacity of over 6 GW, mainly contributed by Adani, Vikram Solar, and Warree. For cells, India holds 2.5 GW, mainly contributed by Adani, Jupiter, and TATA.

Slow progress

The slow progress of projects this year, and decreasing imported module prices, have stopped local cell makers from adding new capacity. Longi is planning to build 1 GW of cell and module capacity, respectively, in India, but the DGTR recommendation also includes the rule that “other developing countries cannot import modules accounting for over 3%, and cells accounting for 9%, of India’s total imports. ”

Countries surpassing these limits will be excluded from the list of exempted countries. This will limit the help from Vietnam and Thailand, which combine to deliver nearly 10 GW of cell capacity. Generally speaking, the goal of meeting the 10 GW annual demand for modules appears unachievable, without China and Malaysia’s PV cells and modules.

On another note, India’s advantage in cost and price will still not be clear, even with a 25% safeguard duty imposed on China, Malaysia, and other developed countries’ cells and modules.

Economies of scale

Popular content

Looking at India and China's overall module costs, most Indian module makers’ production capacities do not have economies of scale that the Chinese makers do. Also the yield rates and the conversion efficiencies of Indian manufactured cells and modules are all slightly lower than current Chinese products. Therefore, India's production costs are not low enough, compared to the Chinese.

For China, with the extreme oversupply situation caused by this year’s new policies, the country’s entire supply chain has witnessed another dramatic price drop. Not only did polysilicon plummet to CNY 80 (US$10.3)/kg for multi-Si wafer use, and CNY 93 ($12)/kg for mono-Si wafer use, but mono-Si and multi-Si wafer prices went down as well.

Because Indian manufacturers all purchase wafers and cells, the difference in production costs between Indian and Chinese modules happens at both the cell and module production level.

Following the 31/5 notification, China’s module assembly costs have decreased to just $0.1-0.11/W, pulling the overall cost of top-tier vertically integrated manufacturers’ conventional multi-Si modules down to $0.23-0.24/W.

Unclear

After the recommended 25% duty, China’s module costs will still be lower than India’s. As a result, whether the safeguard duty can protect Indian manufacturers or not, is not clear. However, it will negatively impact India‘s PV project develoment, such as raising the construction costs of PV power plants, or reducing the efficency of modules.

Looking at July, with undecided duties on cells and modules, and the spot price currently in decline, Chinese module makers and Indian PV project developers have not shown signs of hoarding.

For 2019, China’s demand is likely to stay as low as this year, and it will have difficulties bouncing back. Therefore, the global market demand will need India’s growth, in order to once again exceed 100 GW.

Furthermore, the question of whether India’s trade war will be rolled out is the question concerning manufacturers from across the globe. Should the safeguard recommendation become a reality, manufacturers planning to establish production lines in India will speed up their progress; also, the higher costs of PV projects will affect the Indian government’s planned installation volume.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.