Transport accounts for around one-fifth of global CO2 emissions and is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. That primarily comes from burning fossil fuel for cars and trucks on the road, accounting for around 75% of those emissions. The problem is many fold, but combustion engine vehicles (ICEs) range between just 20% to 35% efficiency – somewhat higher in diesel engines. A typical passenger vehicle emits about 4.6 metric tons of CO2 per year, and some 284 million vehicles were registered in the United States in 2021.

E-mobility: On a greener road to transportation

Urban transportation is key to modern civilization. But it has come at a cost, contributing to a dangerous carbon footprint, high levels of smog, a growing inequality gap, and the destruction of some of our most fragile environments. Thus, in the first quarter of this year, pv magazine’s UP Initiative will focus on the rise of e-mobility and how it can complement the renewable energy transition. Read our coverage here.

Urban transportation is key to modern civilization. But it has come at a cost, contributing to a dangerous carbon footprint, high levels of smog, a growing inequality gap, and the destruction of some of our most fragile environments. Thus, in the first quarter of this year, pv magazine’s UP Initiative will focus on the rise of e-mobility and how it can complement the renewable energy transition. Read our coverage here.One of the reasons for the certain ascendency of electric vehicles is efficiency, not just emissions, or the ability to charge from clean energy. Gautham Ram, assistant professor at TU Delft, said that due to the improvements from electric drivetrains, EVs provide “three to five times improved efficiency” before any maintenance considerations.

“The efficiency, the fact that you get your braking energy back, along with less engine maintenance, brake pads lasting far longer, no oil changes required … it means maintenance costs are going down further.”

Where are the EVs?

A look at the numbers for energy efficiency improvements alone would suggest EV uptake should be swift, and of obvious benefit to health, the environment, and the economy at large, to say the least. What’s taking so long?

Christina Bu, the secretary general of the Norwegian EV Association, points out that the rise of EVs has been remarkably swift, with the pace of technology improvements just as remarkable.

“Remember, Tesla was launched in 2003 but its first car was 2009. The Tesla Model S was in 2012. It’s still not even 10 years ago,” continued Bu. “If you think about that development, it’s now going to go even faster, going forward … you can’t really even picture what’s happening. We’re seeing much more disruption in this industry.”

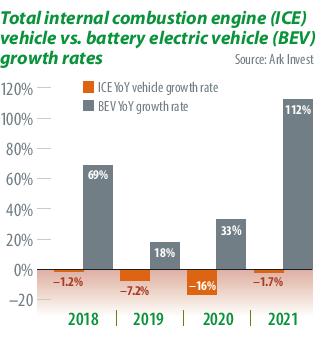

Automakers have now largely shifted toward electric vehicle development. Some 100 new vehicles will be released in the next five years that have a plug – possibly the biggest once-off explosion in a new automotive format. EVs look set to follow the astonishing and rapid growth in solar.

The last month alone saw Lamborghini and Bentley announce new plans to go electric, joining the likes of Audi, BMW, Cadillac, Ferrari, Ford, GM, Hyundai, Mercedes Benz, Tesla, Toyota, and VW, in production, or planning, from innovative small cars to trucks to campers. Startups are also involved, especially in the United States, China, and Europe.

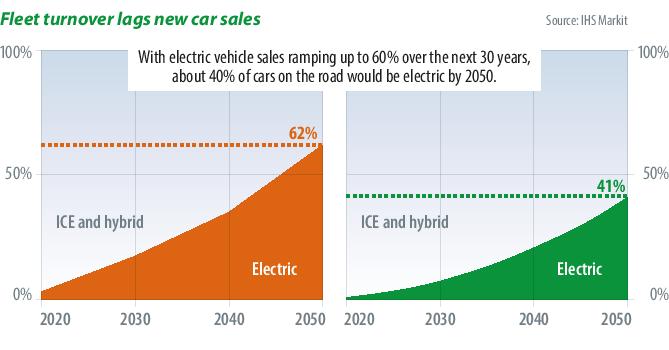

Yet, in the United States, despite green shoots, IHS Markit analysis suggests EVs may only make up one-quarter of new passenger car sales by 2035. In contrast, IHS Markit forecasts the EU could see EV sales reach 50% as soon as 2030.

By 2035, the IHS forecast concludes that just 13% of vehicles on the road in the United States will be electric. The data behind this is that cars are long-lived assets and the renewal cycle slow: the average light-duty vehicle in the country today is 12 years old, up from 9.6 years in 2002.

Even in 2050, IHS projects that the majority of vehicles on US roads will still be fueled by gasoline. Bu disputes this forecast, saying that it doesn’t even approach the likely rate of change – with analysts forced into conservative viewpoints.

“This is just ridiculous,” said Bu. “In Norway, we moved from a full electric market share of 3% in 2012, and in 2022 I expect we’re going to end up at about 80%. We ended up at 64.5% in 2021, fully electric.

“We’re seeing Germany and the UK spend less time moving from 2% to 10% market share than what Norway did. That’s because the technology has developed a lot since. It’s just moving faster and faster in all markets.”

As Bu was careful to point out, Norway’s high sales numbers aren’t because “a bunch of energy efficiency gurus” went about buying the best car for the earth. It’s because of government policies, which included incentives for EV purchases over ICEs.

Those included an exemption on 25% VAT, no purchase/import taxes, no annual road tax, and reduced tolls, all to drive uptake. Some, on passenger vehicles, are being slowly wound back, while commercial vehicle incentives remain.

Norway’s fast lane

Johan Vasara, state secretary of the Ministry of Transport in Norway, told pv magazine that the country started with ambitious political goals for greener transportation. It then implemented practical economic measures to give a “necessary push,” with the market picking up from the momentum later.

“It’s a mix of things. It’s of course, a mix of both ambitious political goals, and the market, which eventually took over to keep the snowball running,” he said. “Norway has the world’s fastest transition to zero emissions in road transport, and for 2021 our numbers show new cars sold now reaching 63.4% of cars that are fully electric [and 21.3% PHEV].”

The ambitions continue, confirms Vasara.

“And we now have further goals. By 2025, our aim is to have all new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles sold by then to be zero emission vehicles. All new urban buses, sold by 2025, must be electric or use biogas,” he said.

“And by 2030, all new heavy-duty vehicles, and 75% of long-distance coaches and 50% of new trucks, should be zero emission vehicles. Especially when it comes to heavy duty vehicles, the technology isn’t yet there. But by setting ambitious goals on a national level, you’re pushing producers, too.”

Vasara was previously the mayor of Kautokeino in Finnmark, a vast area in the far north. It’s Norway’s largest municipality, bigger than the entirety of Denmark, but with just 75,000 inhabitants. Even in this region, said Vasara, there is a growing interest for EVs.

“I have a background as a mayor in the largest municipality in Norway: vast tundra areas and long roads, with, basically, no people living there. Even there, we see a growing interest for electric vehicles – 90% of the transportation people make is happening between your home and your school, kindergarten, and places you manage by charging your car at home. More and more people are realizing that.”

That said, while Norway’s market is firmly established through government policies, it’s not the case in all countries, even where EV uptake is being encouraged.

Alex Barredo, a tech analyst based in Spain, said that despite the potential of sunshine, solar, and EVs, Spain is languishing in comparison.

“Among European countries, Spain has one of the lowest levels of EV adoption. The share of the car market is still under 2.7% in 2021, way behind Western Europe’s 11.2%,” said Barredo. “Political support is there, and incentives are not far from those in other EU countries, but the final sum is a bit of a bureaucratic nightmare to get after a citizen buys the car.”

Ties with solar and other renewables are also there, but mostly with “green-only” electricity supply contracts that pledge to buy the total of energy supplied from renewables. Barredo lamented a very Spanish issue: urban environments, with limited parking garages.

“Infrastructure is the Achilles heel of EVs, and even more so in Spain, which is the European country with the higher share of families living in flats – 66%, versus 16% for the UK and 23% in the EU. This means cheap charging at night while the car is in the garage, which is the best proposition for EVs, is out of the question for most families in Spain.”

Beyond engine swaps

David Tyfield, professor of sustainable transitions and political economy at Lancaster University, pointed out that the shift to an EV is more than just a change in engine. And in urban environments, like in Spain, it will have far-reaching implications.

“I think that we underestimate how big the difference will be, how the EV will change cities and lives. Not just being the dominant number of actual new car sales but dominating the vehicles on the road. Not just private vehicles, but across the board: freight, public transport, light vans,” said Tyfield. “The problem for our understanding, is that people really believe that the electric vehicle is just the existing car system with a changed engine.”

In contrast to this understanding, Tyfield argues that it was geopolitical aspects that informed the growth of the ICE car. The cars America built in the 1950s, the mythology of the open road, and freedom of a vehicle, cemented automobile production as a globalized industry based on the ICE.

“The internal combustion engine car became the mass produced, most consumed article of the post-war boom. The established EV system will be, I think, very different to the internal combustion engine mobility system, and part of a much bigger transformation of mobility in cities. And we remain on the baby slopes still, and nobody knows what the mountain holds in store for us,” said Tyfield.

“We must brace for major shocks still ahead in the route to mainstream decarbonization of transport … including [to] private ownership.”

One element to this profound transformation is vehicle-to-grid technology, increasingly a feature of newer EVs. The path to universal standards to create a grid asset from bi-directional energy flows is still under development, though.

EVs mean solar

Direct applications for solar in relation to EVs apply at different scales. At one level, Bu said that EV ownership is driving solar take-up.

“The interest in solar panels is really going up and especially last year. The crisis in prices on electricity in Europe happened in Norway, which has really never happened to this level before, because we have had an abundance of electricity. And right now, it’s the companies installing solar panels that are struggling,” said Bu. “There’s so much demand, they can’t really deliver enough.”

“We run a survey question [in an annual report] asking whether people get more interested in energy efficiency and so on after getting an EV, and the majority say yes. Our members get an EV and they go on, get solar panels, they start looking at everything to make homes as efficient as possible when it comes to energy use.”

At the other end of the discussion is the large scale, where PV suppliers and participants are starting to think about the future.

One example is Enphase Energy, which acquired EV charging market supplier ClipperCreek late last year, and it is unlikely to be the last tie-up between operators.

Frank Gordon, head of policy at the Association for Renewable Energy and Clean Technology (REA), told pv magazine that in the UK, solar farm developers looking for loads may need to think creatively for future offtakers, such as charging stations.

“We have seen the news that the UK may have as much as a 35GW subsidy-free solar farm pipeline, so this section of the market is developing well,” said Gordon. “Developers may now have challenges in terms of finding offtakers if the market starts to become saturated and there is no new government support via extra Pot 1 contracts for difference (CfD) auctions. The current UK CfD auction is underway but there are no further dates for the next ones.

“The integration of solar PV and EV charging stations, both large-scale and on-site, may represent an increasingly useful route to market for solar developers. There is room for growth in areas such as solar car park canopies with integrated EV charging.

“We would like to see eased grid connection conditions, more CfD auctions, and a favorable distribution network operator (DNO) price control settlement to unlock barriers on the regional grids in order to help enable this, underpinned by deep and transparent national flexibility markets for energy storage.”

Vehicle-integrated PV

In January of this year, in a concept car launch, Mercedes-Benz added 117 solar cells to the rooftop of its Concept Vision EQXX car. Working with Fraunhofer ISE, the company stated the vehicle-integrated PV (VIPV) system could add 25 km of range each day.

A Fraunhofer ISE study in September last year focused on commercial vehicles including electric vans and trucks, found the fastest payback period of 3.4 years came for rural VIPV delivery trucks. The study suggests VIPV will become more viable over time, with mass production of VIPV components lowering costs, and the continual improvements in PV efficiency.

Gautham Ram was more cautious on VIPV for passenger vehicles, suggesting that additional rooftop PV would be more effective.

“I expect some or many EVs to adopt this idea, especially if the economics of it become more attractive. How much solar we can add to the car depends on if you add to the existing roof or design the vehicle bottom up to maximize the PV area [like Dutch startup Lightyear],” said Ram.

“[But for passenger vehicles] I am not sure of the payback period. VIPV will cost much more than rooftop PV. The yield is much lower owing to non-optimal orientation of the car roof and shading from the environment … a larger rooftop system at the office or home might give yield through better orientation, and be cheaper overall.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.