Cambodia's Great Lake, the Tonle Sap and Vietnam's Mekong Delta are suffering harmful impacts from the suppression of the Mekong River's annual flood pulse – a consequence of the operation of hydroelectric dams far upstream in Yunnan, China, and on tributaries of the Mekong in Laos and Vietnam. Many more dams are planned. If they are built, Cambodia will see the end of the reverse flow that supports the enormously fecund flood pulse at the Tonle Sap. Subsequently, in the dry season, Vietnam will be starved of the fresh water that supports its delta ecosystem and food security.

This brief proposes an alternative approach: A floating solar power system on the Tonle Sap, built on a scale that will satisfy Cambodia's power needs at lower cost.

Can the sun on the Great Lake Project save the Mekong and Vietnam?

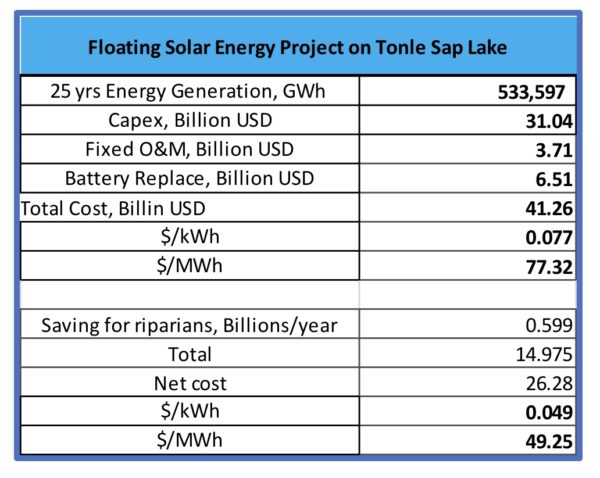

The answer is ‘yes!' and the feasibility analysis in this report seeks to prove that a 25-year program for a 28 GW floating solar project with 4-hours battery storage will meet Cambodia's projected energy needs to 2045 at the cost of US$31 billion.

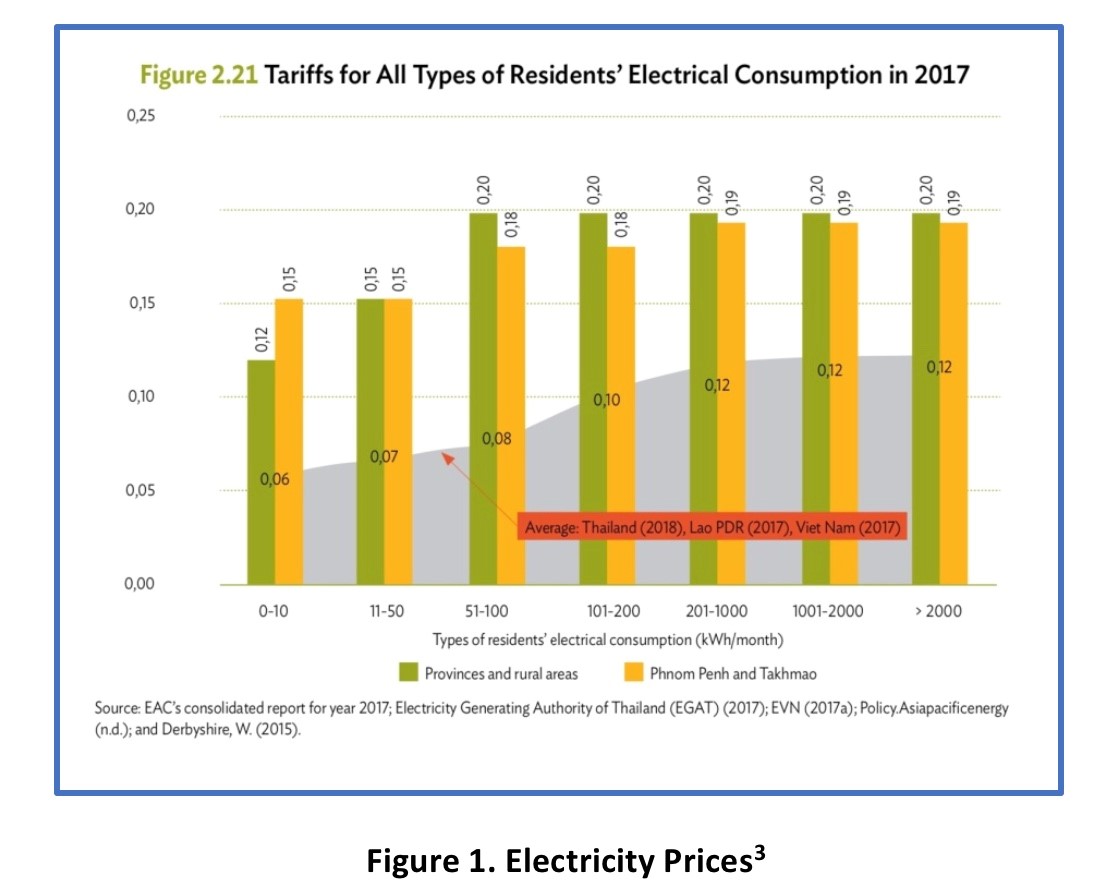

The high cost of electricity in Cambodia

Cambodia is the least developed and most energy-thirsty country in Southeast Asia. The price of electricity in Cambodia is the highest[1] in the region, ranging from $0.15 to $0.18 per kWh. In some rural areas, the price reaches $0.50 to $1.00 per kWh.[2] By comparison, the price in Thailand ranges from $0.105 to $0.143 per kWh, and in Vietnam from $0.072 to $0.126 per kWh.

Hydroelectricity in Cambodia is not cheap

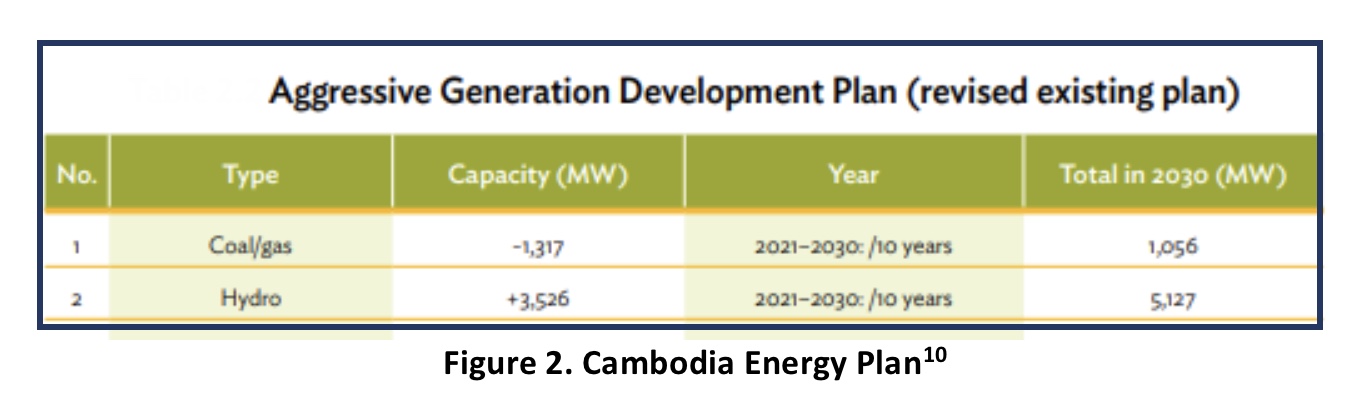

Cambodia’s 2030 energy plan includes several new coal and gas fired power plants plus two giant hydroelectric projects—the run-of-river Stung Treng[3] (980 MW) and Sambor[4] (2,600 MW) power plants on the Mekong mainstream. These two hydroelectric projects face strong objection both from local communities and from Vietnam.

The International Rivers organization reports that: “The Sambor Dam would be a tragic and costly mistake for Cambodia. Cambodia’s fisheries safeguard the food security of millions of subsistence fishers and contribute over 15% to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).”[5]

The Natural Heritage Institute (“NHI”), a U.S.-based international research organization, studied the Sambor Dam project and recommended the Cambodian Government defer any commitment to Sambor Dam and, instead, pursue better alternatives. The NHI reports:

- Out of a total sustainable fisheries yield in Vietnam and Cambodia of 1.2 million tonnes/year, 38% of all fish are migratory — 70% of these would be affected because they have their spawning grounds above Sambor, and these will suffer a 100% reduction (because mitigation is not feasible). At a net value to fishermen of USD 1.50/kg, this represents a loss of USD 479 million/year.

- On the basis of productivity differences of paddy fields in An Giang province, between fields that receive 2.5cm/year sediment deposition or none, a total value of the sediment load at Sambor of USD 120 million/year is estimated. At a trapping efficiency of 62%, the Sambor reservoir would reduce this value by USD 74 million/year.

The two hydropower projects together will hold back in their reservoirs 3.8 km3 water and permanently inundate 831 km2 of land. The Sambor and Stung Treng dams will inflict costly damage on the livelihoods of the surrounding population and offer them no compensation. What they produce for the people instead is expensive electricity with harmful effects.

It appears the N.H.I report may have turned Cambodia definitely away from hydropower. Cambodia has signed a 30-year Power Purchase Agreement[6] at $0.077/kWh[7] with Sekong Power and Mineral Company Limited and Xekong Thermal Power Company Ltd from Laos for electricity from coal, a project which will take at least four years to construct.

What does this study offer Cambodia?

In July, 2019, the Director General of Electricité Du Cambodge (“EDC”) said that he does not wish to see the Sambor and Stung Treng hydroelectric projects as part of Cambodia's future energy development plan.[8] He did not mention an alternative that will meet the country's power needs. But Cambodia desperately needs an alternate energy source, and this situation prompts the author of this paper to explore the technical and economic feasibility of a floating solar power generation system (FSS) on the Tonle Sap Lake and propose it as an alternative to the hydroelectric projects and perhaps also some of the coal and gas plants in the current Cambodia energy plan (summarized in Figure 2 below).

Why choose the Tonle Sap “The Great Lake” for the floating solar system?

The Great Lake, also known as the Tonle Sap, offers overwhelming advantages for a floating solar energy plant. These include:

- The Great Lake is a huge, centrally located public surface near to Cambodia's capital, Phnom Penh, where 90% or electric demand is concentrated.

- The Great Lake receives the highest level of solar irradiance in the Mekong River Basin[9].

- Floating solar arrays produce 11%[10] to 16% more energy[11] than arrays sited on land.

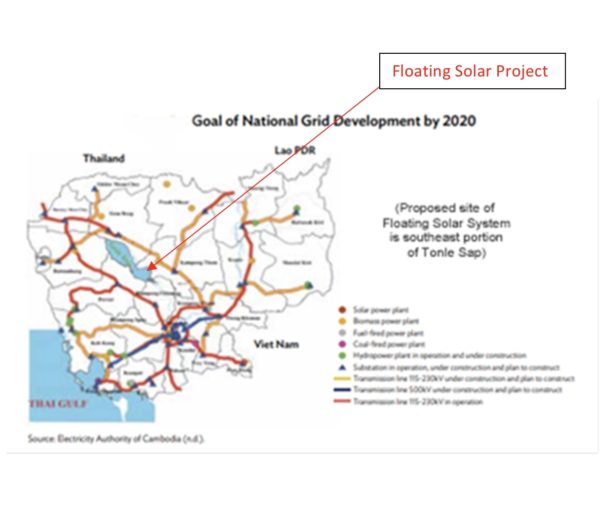

- Proximity to existing 230 kV national grids means that connection costs will be relatively low (see Figure 3).

Description of the floating solar plant (FSS)

Description of the floating solar plant (FSS)

Table 1: LCOE for this project is 7.73 cents/kWh and 4.93 cents/kWh if avoided loss is credited.

- This proposed FSS is to be constructed in phases over 25 years on the Great Lake. The total capacity is 28.5 GW, with 88 GWh storage, generating 508 tWh in 25 years.

- The entire project would cover a direct area of 330 km2, gross area of up to 400 km2, which is 15% of the Great Lake’s dry season surface and about 2.4% of its wet season surface. At this relatively small percentage of the Great Lake’s total area, the impact of the project on aquatic life would be insignificant. It may even benefit the Great Lake by lessening algae growth and reducing the loss of oxygen.

- The FSS requires 400 km2 of open water surface area but helps save 831 km2 of permanent land loss to the Sambor and Stung Treng reservoirs (if constructed). The FSS would preserve $15 billion in the inland fisheries economy (as avoided loss to them).

- The LCOE of 7.73 US cents/kWh is slightly more than 7.7 US cents/kWh Cambodia would pay for electricity generated at Laos’ Xekong coal-fired power plant. The real LOCE to the Cambodia should only be 4.93 US cents/kWh since the riparian population will not have to bear the losses associated with the hydroelectric plan.

- Vietnam was disclosed to be the buyer of 70% electricity generated by the Sambor hydroelectric project,[12] a plant that may not be built. Vietnam’s government can look hard at its own energy plan, where the fast-falling costs of renewable energies (including wind and tidal wave energy in addition to solar) should permit it to satisfy its needs more economically and with greatly reduced external costs.

- Considering that there will be 28 job-years needed for each MWp[13], this project will support 500,000 job-years for Cambodian fishermen.

- Considering the ecological importance of the environmental flow and the livelihoods of 30 million Mekong people, the next question is, will Cambodia and Vietnam’s governmentstake a step back from hydropower and fossil fuels and formally investigate the feasibility of the floating solar energy as demonstrated in this report?

Based on this feasibility analysis, the Sun on the Lake project could save the Mekong for Cambodia and Vietnam. Solar energy requires that a smart grid and transmission network be put in place in time to balance fluctuating demand. However solar plants can be constructed to supply electricity in matter of months and can be phased in as demand is confirmed – a feature that no other source can match.

Please contact the author if you would like to see his methodology.

[1] https://aecnewstoday.com/2019/cambodia-electricity-to-stay-higher-than-neighbours-as-eba-jitters-emerge/

[2] https://energypedia.info/wiki/Cambodia_Energy_Situation

[3] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stung_Treng_Dam

[4] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sambor_Dam

[5] https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/sambor-dam

[6] https://www.phnompenhpost.com/business/kingdom-okays-2400mw-power-purchase-laos

[7] https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50642313/cambodia-and-laos-to-sign-2400-megawatt-power-deal-today/

[8] https://www.phnompenhpost.com/opinion/good-news-mekong

[9]https://www.dropbox.com/s/z8yvyum07wcjcaf/Volume%203_Solar%20Alternative%20to%20Sambor%20Dam.pdf?dl=0

[10] https://res.mdpi.com/d_attachment/applsci/applsci-09-00395/article_deploy/applsci-09-00395.pdf

[11] “Although floating panels are more expensive to install, they are up to 16 percent more efficient because the water’s cooling effect helps reduce thermal losses and extend their life.” https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/02/in-land-scarce-southeast-asia-solar-panels-float-on-water/

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sambor_Dam

[13] http://stalix.com/Solar%20Energy%20Job%20Creation.pdf

About the author

Long P. Pham has 40 years of experience as a professional mechanical engineer in California, and is the founder of the Viet Ecology Foundation, an NGO based in the U.S. Pham founded Moraes/Pham & Associates, Inc. and Advanced Technologies Consultant Inc. and serves as Principal-in-Charge, directing Facility, Safety and Code Compliance projects for advanced semiconductor and pharmaceutical companies, such as Hughes Aircraft Co, Genentech, ASML Cymer, AMCC, ABOTT, Solar Turbines.

Long P. Pham has 40 years of experience as a professional mechanical engineer in California, and is the founder of the Viet Ecology Foundation, an NGO based in the U.S. Pham founded Moraes/Pham & Associates, Inc. and Advanced Technologies Consultant Inc. and serves as Principal-in-Charge, directing Facility, Safety and Code Compliance projects for advanced semiconductor and pharmaceutical companies, such as Hughes Aircraft Co, Genentech, ASML Cymer, AMCC, ABOTT, Solar Turbines.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The study apparently only looks at batteries for storage. Cambodia is relatively flat, but the Blakers atlas shows a number of potential sites in SW Cambodia,. There are far more in hilly Laos and Vietnam. Off-river closed-cycle PUHS takes little land and has minimal impact on water flows.

Your comment is well received, yes PHES (Pump hydro energy storage) uses very little water and has been technically and economically proven feasible. A proposed PHES 500 MW is being implemented at Lake Elsinoire, CA. In Cambodia, inhabitants livelihoods and activities depend heavily on water, the daily cycle rise and fall of water level induced by PHES operation may have serious impacts to them. If this can be assessed and mitigated, PHES may be less costly than battery option.