JGC Corporation and the Japanese National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology have demonstrated a system that uses solar power to produce hydrogen, which is then converted to ammonia in an energy-efficient manner, and then used to generate electricity by combustion in a gas turbine. The process is “CO2-free from production to power generation,” reads the joint press statement.

JGC says it has developed a ruthenium based catalyst to synthesize ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen at low temperature and pressure. Ammonia is an “ideal energy carrier for hydrogen,” says the press statement, in part because using hydrogen as a fuel raises “questions of cost and safety, [and] efficiency of transport and storage.” Ammonia also “contains a large amount of hydrogen, is easily liquefied and is already widely used as a fertilizer, meaning that a supply chain is in place.”

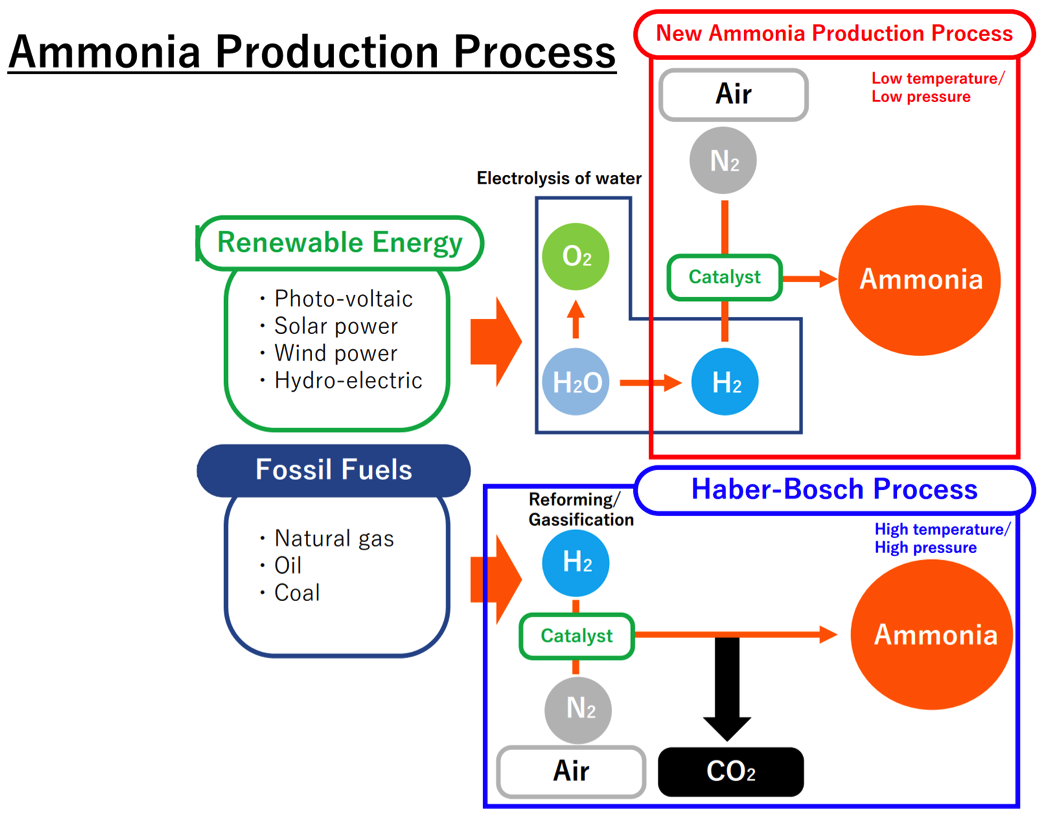

JGC’s new approach to producing ammonia is described in the following diagram, compared to the conventional process at the bottom:

As for round-trip efficiency, the first step of producing hydrogen via electrolysis of water could soon reach an efficiency of up to 90%, according to the U.S. Energy Storage Association. As for the second step of converting hydrogen to ammonia, JGC did not disclose the efficiency of its process, while for the third and final step of combusting ammonia, a research presentation by Hideaki Kobayashi of Tohoku University showed that the thermal efficiency of combusting an ammonia-air mixture was close to that for combusting a mixture of methane (natural gas) and air; nitrogen oxide emissions were reduced via selective catalytic reduction.

Japan intends to create an “innovative low-carbon hydrogen-fueled economy” by 2030, according to JGC’s joint statement with the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science, and to “take the lead in hydrogen-related industries on the world market” through its energy carriers research.

Australia is also evaluating renewable produced hydrogen, with the Australian Renewable Energy Agency having issued a report on the topic last August.

Meanwhile, The United Kingdom's Committee on Climate Change noted in a November report that “hydrogen could be produced at low cost … from solar power near the equator. This would need to be imported via ships, either as hydrogen or another energy carrier such as ammonia.” The committee projected that for England, “burning hydrogen in power stations will be cost-effective against the government’s carbon values in the 2030s.”

Achieving scale in converting renewable power to ammonia could be aided via the shipping industry. The International Renewable Energy Agency said in an April 2018 report that its “overall recommendation for developing P2X [renewable power to fuel] is to focus on the development of ammonia for the shipping sector as well as long haul road transport, where few or no competing low carbon technologies exist and P2X is expected to be economically viable.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Ammonia can be used directly as a fuel, in heat engines or fuel cells – even rockets. Since it’s a third as dense energetically as oil fuel the prime candidate is ships.

Ammonia’s big technical advantage over hydrogen is its much higher boiling point, just -33C: in between propane and butane, which are moved around as liquids in pressurised cylinders and at ambient temperature, on a large scale.

The alternative path to P2X is via methane, the main ingredient in natural gas. This has a huge existing distribution network and millions of installed burners from kitchen hobs to gas turbine power stations. The carbon dioxide emitted is sustainable as long as the carbon source is biomass. Because plant cellulose has a higher ratio of carbon to hydrogen than methane, even complete biodigestion leaves a carbon-rich residue available for P2G. But methane is a powerful greenhouse gas in its own right, unlike ammonia, and the leaks (at any rate in the USA ) are out of control.

The diagram is wrong. No carbon dioxide is produced in the Haber Bosch Process. Conventionally carbon dioxide is produced in the hydrogen production part of the process. Typically this is during the steam reformation of methane, usually natural gas. Thus, unless the process is different than shown, all this is, is the Haber Bosch process with a better catalyst.

The existing process can take hydrogen from any source including from electrolysis using renewable electricity but usually does not because the natural gas route is cheaper.

Likewise, the new process with the improved catalyst, will still be cheaper run on methane derived hydrogen.

The new catalyst may run at a sufficient rate at lower temperatures and pressures but Le Chatelier’s principle still applies. The reaction goes from 4 gas molecules to 2 gas molecules so increasing the pressure will increase the conversion in a single stage. The overall reaction is endothermic so raising the reaction temperature will increase the conversion at a single stage.

Although it would be very good to see ammonia generated from renewable energy, without state intervention, it is likely that the industry will say thank you for the improved catalyst and carry on with steam reformation of natural gas.