From pv magazine 09/2021

Since 2020, the wafer, cell and module segments have been rapidly expanding, bringing total capacities to 264 GW, 322 GW, and 365 GW, respectively, by the end of the first half of 2021. Each segment is expected to reach 365 GW, 439 GW, and 463 GW, respectively, by the end of this year. The global output of polysilicon is projected to reach 550,000 metric tons this year, which can supply around 190 GW of module production.

The polysilicon business outlook seems good over the short term. However, trade disputes between the United States and China bring uncertainty. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has issued a withhold release order (WRO) against Xinjiang-based Hoshine Silicon Industry, restricting imports of silica-based products related to the company and its subsidiaries. The U.S. Senate also passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act to prohibit the import of all goods produced in Xinjiang. As Xinjiang is a manufacturing hub for silicon metal and polysilicon, considerable discussions on the impacts of the restrictions have begun.

Looming impacts

While the WRO doesn’t restrict polysilicon imports, some module manufacturers face the risk of having their products seized, as their materials may come from Hoshine, the largest silicon metal supplier. According to the ‘Reference Hoshine Frequently Asked Questions’ published by CBP, importers of solar products entering the United States need to provide documents that can trace the supply chain and show that the silica used in the products was not sourced directly or indirectly from Hoshine or any of its subsidiaries.

Downstream manufacturers say it is difficult to provide such information due to the complicated nature of polysilicon production. As of August, modules of some manufacturers are reportedly being seized by CBP officers, with some being released shortly afterward. At present, the CBP scrutiny standard and specific measures remain unclear.

If the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act is approved by the United States House of Representatives and signed by President Biden, the import of all goods produced in Xinjiang will be banned. Polysilicon manufacturers based in Xinjiang including Daqo New Energy, Xinjiang GCL, TBEA and East Hope, as well as manufacturers that use silica from the region, will take the first blow.

Supply/demand forecast

Beyond the U.S., Canada and Mexico are likely to impose similar sanctions. The EU, with several member states having recently passed or drafted laws to tackle forced labor in supply chains, might be next. Australia and Japan have also voiced concern about human rights violations in Xinjiang and may soon follow suit with restrictions on goods from the region.

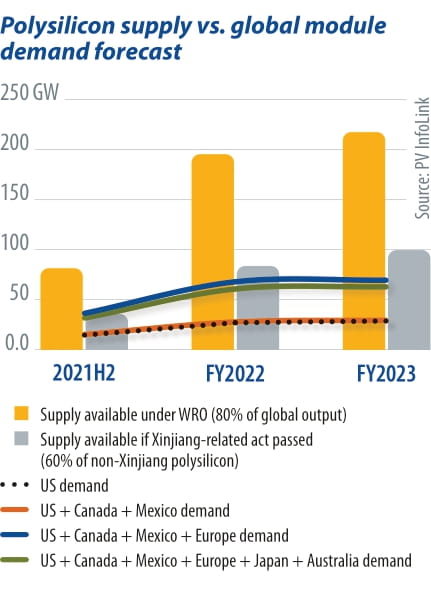

Xinjiang accounts for 35% to 40% of global silicon production. Hoshine, the world’s largest silicon metal manufacturer, takes up 20%. PV InfoLink estimates that 20% to 40% of polysilicon may be restricted from the U.S. or Europe.

The estimates show that around 20% of polysilicon will not be able to supply Europe or the U.S. if the WRO only applies to Hoshine. However, polysilicon production outside of Xinjiang can supply 82 GW in the second half and 196 GW and 218 GW, respectively, for 2022 and 2023, which is sufficient to fulfil demand from the U.S. and countries likely to impose import restrictions. Having said that, manufacturers should pay attention to whether CBP officers will seize an individual unit of import for investigation. Module supply to the U.S. market may be slightly impacted for the short term.

If the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act is passed, polysilicon produced by Daqo, Xinjiang GCL, TBEA and East Hope in Xinjiang will no longer be usable for the modules that are exported to the U.S. In addition, after deducting around 40% of polysilicon in other regions that use silica from Xinjiang, there will be around 33 GW, 84 GW, and 100 GW of polysilicon available in the second half of 2021, 2022, and 2023, respectively – enough to serve the U.S. market.

However, if Europe, the second-largest market, bans imports from Xinjiang this year, polysilicon shortages will immediately occur in regions outside of Xinjiang in the short term. If this happens in 2022, polysilicon supply outside of Xinjiang will be in a tight balance and run slightly short in the high season. Under a 2023 scenario, overall polysilicon supply will be in surplus again after large volumes of new capacity come online.

It appears that both WRO and the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act will not affect U.S. demand markedly. Whether solar demand will cause polysilicon shortages due to the Xinjiang issue in the next two years depends on the actions of European countries. Currently, Germany and Norway’s passing of laws combating forced labor in supply chains are variables that may impact solar exports to Europe, although Germany hasn’t come out with measures on import restrictions. Meanwhile, the European Parliament is drafting Xinjiang-related regulation and policy, and polysilicon market trends are subject to their progress and decisions.

![]()

The impacts of Xinjiang-related issues on the industry will be less severe after 2023, no matter when specific legislation is passed. Polysilicon manufacturers have made large profits over the past year amid soaring polysilicon prices. Apart from Tier-1 manufacturers that are expanding capacity at a large scale, REC Silicon, CSG Polysilicon and LDK – whose lines have been shut down – are evaluating the feasibility of resuming production. High profitability attracts new players, such as Xinjiang Jingnuo, Lihao Semiconductor, Baofeng Energy and Runergy, all of which plan to expand capacity outside of the Xinjiang region to hedge political risk. If these new furnaces come into operation as scheduled, total polysilicon capacity will far exceed demand, leading to fierce price competition. If Tier-1 polysilicon makers that bring capacity online earlier cause prices to decline due to surplus, new players that enter the competition later, or Tier-2 manufacturers that plan to reopen lines, may turn conservative about their capacity expansion plans.

About the author

Corrine Lin is the chief analyst at PV Infolink. PV InfoLink is a provider of solar PV market intelligence focusing on the PV supply chain. The company offers accurate quotes, reliable PV market insights, and a global PV market supply/demand database, as well as market forecasts. It also offers professional advice to help companies stay ahead of competition in the market.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

And you need also take in account in your analysis that recently closed capacities like OCI in Korea, and REC Silicon in USA could restart their capacities soon. They are not under threat of US restrictions and could be profitable immediately at the actual market price…