The long-standing misconception, in the United Kingdom, that co-located energy storage doesn’t work is rapidly crumbling. Over the last two years, nearly half of all permitted solar developments in the United Kingdom had co-located storage systems, marking a significant shift in the renewable energy landscape. In time, the co-location of storage may become the default development model for renewable energy in the nation.

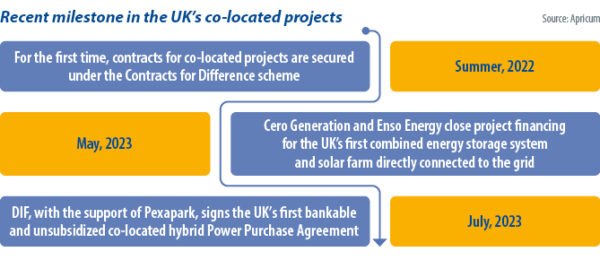

Several crucial storage co-location milestones have been achieved in the past 18 months. Firstly, in mid-2022, co-located projects secured deals under the contracts for difference (CfD) incentive, after an amendment permitted co-located storage as part of CfD agreements.

Secondly, in May, Cero Generation and Enso Energy closed project financing for the United Kingdom’s first combined energy storage system and solar farm directly connected to the grid. More recently, in July, with the support of Swiss consultancy Pexapark, Dutch investment fund DIF Capital Partners signed the United Kingdom’s first bankable, unsubsidized, co-located hybrid project power purchase agreement (PPA) with French utility company Engie for a 55 MW solar project co-located with 40 MW of storage.

While specific to the United Kingdom, the trifecta of subsidy eligibility, project finance availability, and PPA demand is a major step change to commercializing the solar-plus-storage pipeline. The typical scale of storage capacity is shifting from 20% of generation capacity to more than 100% at a growing number of sites, and Apricum sees more and more large investors now preferring co-located projects.

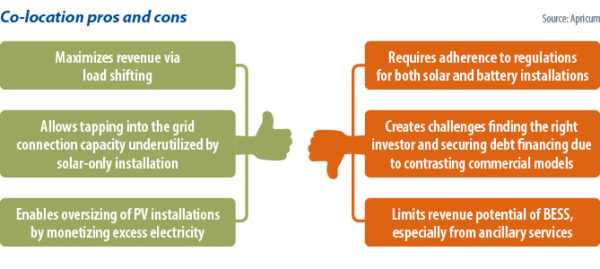

As the appetite for co-located facilities grows, driven by their benefits, several challenges need addressing to ensure widespread adoption. There are numerous benefits of co-locating solar and storage in the United Kingdom.

Resolving cannibalization

At a generic systems level, as the penetration of renewables accelerates, each incremental project is more exposed to the impact of “cannibalization.” The phenomenon occurs when the success of solar in driving down electricity prices reduces returns for future PV sites. High solar-penetration markets, therefore, have the greatest need to mitigate potential cannibalization impact. Load-shifting, via the co-location of storage, is one way of doing this. Energy storage protects long-term asset value and is increasingly seen as enhancing the value of PV projects.

Grid connections

Long lead times for permitting and grid connection have been significant barriers to renewables deployment, not just in the United Kingdom but across Europe. While solar-only projects often use less than 20% of their grid connection capacity, energy storage systems at co-located projects can utilize some of the unused capacity for additional revenue streams. In some cases, these revenues mitigate the capital cost of the storage system.

Over-scaling capacity

Battery-coupled projects are preferred by solar developers because excess electricity that cannot be exported to the grid due to constraints can be stored and monetized. If a system is DC-coupled – the battery is connected to solar on the DC side and only one inverter is used, compared to separate solar and battery inverters for an AC-coupled system – the storage can prevent excess clipping of electricity production by a solar inverter. In both cases, co-location enables the oversizing of generation capacity, thus maximizing revenue from the industry’s principal constraint – grid connection capacity.

Despite these benefits, it is not a given that solar projects will always be developed alongside energy storage systems. There are technical and market challenges and potential drawbacks to that approach.

Planning, permitting

Co-located projects require adherence to regulations for both solar and battery installation, adding complexity to permitting within an already challenging process. Furthermore, if a solar developer, having already obtained a grid permit, decides to add storage capacity to the project, the connection date may be delayed. Favorable changes in regulations and permitting processes are expected as more co-located projects come online.

Deal structuring

Solar and storage projects have contrasting commercial models. Solar projects offer long-term, secure revenues while battery storage projects operate in the merchant market, with 85% to 95% of revenues coming from ancillary services to the grid. Backers of these two types of contracts typically had divergent risk tolerance, which impeded investment. Splitting the contracts with different parties creates operational challenges and disputes over grid connection.

Popular content

Additionally, debt funding remains challenging due to the relatively novel nature of co-located ventures, as financial institutions have typically perceived them as higher risk, leading to higher interest rates, lower returns, and, henceforth, limited investor interest. This is now changing as merchant risk-tolerance thresholds increase, and particularly as utilities and energy players displace financial investors as the principal acquirers of solar assets. Power companies bring higher merchant appetite and less reliance on project finance.

The examples of hybrid PPAs and project financing for co-located projects mentioned above demonstrate that these offtake and funding challenges are starting to be overcome – even for financial investors. Hybrid PPA contracts are also expected to move from separate contractual agreements for renewables generation and storage assets, like the PPA signed by DIF Capital Partners, towards a single blended contract supporting 24/7 green energy supply.

Revenue constraints

Battery energy storage system developers may be hesitant about co-locating with solar due to the merchant revenue impact. Grid constraints mean solar electricity export is prioritized, which can limit a battery’s revenue potential from ancillary grid services such as frequency response. Efficient DC-coupled connections further limit the ability to perform ancillary services. As a result, investors and buyers often prefer AC coupling. Finding the right trade-offs and tuning trading algorithms accordingly, becomes crucial to minimizing losses.

Tech challenges

The technical integration of energy storage systems with solar demands meticulous engineering expertise, which increases development time and costs. For example, grid constraints may prevent solar and storage capacity from exporting simultaneously beyond certain limits, to avoid fines from distribution network operators. To comply, exports must be controlled and limited by hardware and software on the sites.

Looking ahead

While only eight co-located projects have been brought online in the United Kingdom to date, Apricum said it is confident that the share of co-located projects will rise significantly across the country’s traditional renewable energy markets. This will especially be the case in regions where penetration is high, and cannibalization and grid constraints pose growing risks.

In Spain, for example, €150 million ($159 million) in grants was awarded for energy storage co-located with renewables in 2022. This kind of supportive government policy, in combination with increasing cannibalization, is already driving investors to look into co-located projects. Germany has also introduced a subsidy scheme favoring hybrid projects, which also signals a positive future for co-location and has brought about projects such as the solar-plus-storage site commissioned by Enerparc in April.

Developers venturing into co-located projects face significantly more complexity with permitting and contracting, financing, and technology planning. Strengthening contract structures and risk management capability will be imperative to fully realizing the benefits of co-location. However, these upfront investments create more resilient and valuable long-term assets.

This increased complexity spreads to transactions, too. Monetizing co-located development assets requires a more sophisticated vendor or broker than one selling standalone project rights. The pool of competent advisers and buyers is narrower. Apricum’s depth of modeling, engineering, and financing competence distinguishes its services and it expects to play a growing role in transacting co-located assets throughout the United Kingdom and across Europe.

About the authors: Charles Lesser leads Apricum’s transaction advisory mandates. He helps companies to navigate energy storage, green mobility, digital energy, and merchant risk. He has more than 22 years of experience in energy investment banking, advising public and private companies from startup to listing, capital raising, mergers and acquisitions, and strategic transactions. He previously served as managing director and head of natural resources at Panmure Gordon.

About the authors: Charles Lesser leads Apricum’s transaction advisory mandates. He helps companies to navigate energy storage, green mobility, digital energy, and merchant risk. He has more than 22 years of experience in energy investment banking, advising public and private companies from startup to listing, capital raising, mergers and acquisitions, and strategic transactions. He previously served as managing director and head of natural resources at Panmure Gordon.

Alexandra Popova is a management consultant focused on clean-tech strategy development and advanced analytics. Before joining Apricum, she worked as an engagement manager at McKinsey & Company, where her projects included developing a technology roadmap for an energy company, supporting the global launch of a digital player in the energy retail space, and carrying out a market assessment for an energy generation startup.

Alexandra Popova is a management consultant focused on clean-tech strategy development and advanced analytics. Before joining Apricum, she worked as an engagement manager at McKinsey & Company, where her projects included developing a technology roadmap for an energy company, supporting the global launch of a digital player in the energy retail space, and carrying out a market assessment for an energy generation startup.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.