It is easy to forget how small changes can sometimes reap the most dramatic benefits. Take the humble fridge. What was once a marvel of technological prowess, has become standard fare. To many in the western world, that is.

To those living off the beaten track, off the grid, up in the dusty red Burmese mountains, a fridge can be revolutionary. “Food supply and security in these remote regions is hard and fridges can be a lifesaver,” Nathalie Risteau, CEO of greentech solutions company, Mandalay Yoma, tells pv magazine. Indeed, not only can individuals access fresh produce, but fridges can also be run as small businesses.

Mandalay Yoma is working with Myanmar’s Department of Rural Development (DRD), the German Corporation for International Cooperation GmbH (GIZ), and the World Bank to electrify remote communities via personalized PV mini-grids. Last year, it successfully completed the country’s largest: a 120 kWp system in Myaing.

The grids are transforming villages – allowing inhabitants to work and study after the sun has set, run small businesses, establish healthcare facilities, and power agricultural efforts via solar water pumps. To date, the company has installed mini-grids in three villages, which generate electricity for 2,000 inhabitants. Overall, the aim is to equip 1,000 villages.

Risteau says these grids are cheaper and more reliable than existing sources of energy, like diesel generators and candles. A contract is signed with the village, allowing it to take collective responsibility for its energy system, which is run on a pre-paid meter. It takes around three months to install such a grid and the government allocates subsidies through the DRD. “The costs are … [around] $1,000 per household,” says Risteau.

Surprising penetration

Myanmar has come a long way in a short time, having been set on a democratic path after the National League for Democracy (NLD) party gained a majority in the 2015 general elections.

While problems are still rife, and the new government grapples with negative side effects of a more open market, positive developments have been made, the biggest of which, arguably, has been the National Electrification Plan (NEP) (see table, top p. 38).

Bill Gallery, Project Manager of Lighting Myanmar – part of the International Finance Corporation’s and World Bank’s Lighting Global program, which enables energy access through off-grid projects – tells pv magazine the penetration of solar in the country is surprisingly high, having grown from 9% in 2014 to 25-27% in 2016. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it is over 30% in 2017,” he says. According to the latest statistics from the World Bank, households served with solar as of June 2017 totaled 140,000. By 2020, 50% of Myanmar’s population can expect to have access to electricity. By 2025, this should have risen to 75%, with universal access achieved by 2030.

Low cost competition

Lighting Myanmar has three main goals – business development, consumer education, and policy and regulation – to help companies enter the market, and create a sustainable solar industry. One of the biggest challenges, Gallery says, is local, low cost competition. “There are lots of cheap panels and batteries on the market,” he says, adding that the current industry is very informal, with panels coming in over the Chinese border, and distributed to local shops. Residents then buy and assemble systems themselves.

Informal distribution raises problems of safety and quality, says Gallery. He is working to address these, by setting quality standards, and educating consumers and businesses. At a global level, the IFC works with 50 companies, offering over 130 quality solar products, and it is working to introduce these to the Myanmar market. While these higher quality systems are more expensive – typically twice as much as the $40-50 for a small solar home system (SHS) on the informal market – the benefits of longevity and higher power output outweigh lower prices. And, coupled with government subsidies, they are viable for residents. Nurani Robelus, World Bank spokesperson for the NEP says subsidies for off-grid SHSs vary, according to size. For systems between 30 and 60 W, they range from 75 to 84% of costs, while for larger systems, it is 44 to 73%.

The Myanmar National Electrification Project (NEP)

| Date | 2015 – 2021 |

| Aim | The NEP is expected to benefit over 6.2 million people by bringing electricity to more than1.2 million households. |

| Costs | US$567 million, of which $400 million is coming from the World Bank |

| Overview | Component 1: Grid extension, $300 million Component 2: Off-grid electrification, $ 80 million Component 3: Technical assistance and project management, $20 million |

Source: Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy

Market-based models

The World Bank is also working with the DRD to roll out a results-based financing (RBF) pilot program early this year, under which subsidies will be paid for the sale of solar systems through the private sector and NGOs. The idea is to develop more market-based models, such as Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) and Monetary Financial Institutions (MFIs). “By getting more companies to market, and to scale up, you are building the market for the long term and reaching more people,” says Gallery. While the final details were still being worked out at the time of going to print, he says there have been promising early signs for these models, which have seen success in such markets as Africa and Bangladesh. In December, Singapore’s SolarHome installed 1,000 PAYG solar systems in rural Myanmar.

Number one driver

By far the biggest focus of the government is off-grid electrification. “Off-grid solar is the number one driver of electrification in Myanmar,” says Gallery. Under the off-grid component of the NEP, adds Robelus, “SHSs have reached 2,700 villages in 95 townships, benefiting nearly 700,000 people residing in 140,000 households.” A further 186 schools and 524 health centers have access to electricity, and delivered eight pilot hybrid solar mini-grids in 2017. Looking ahead, she says 100,000 SHSs are under procurement and will be installed across 1,400 villages this year.

What is also positive is the high number of women involved in off-grid. At off-grid renewable energy workshops held by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2016 and 2017, over 50% of trainees were women, it reported.

Business case

Despite the dominance of off-grid, there is a business case for commercial and industrial (C&I) rooftop installations. Mandalay Yoma’s Risteau says that while the sector is in its infancy, the potential is huge, because of the high diesel costs, an unreliable grid, and a lack of power backup by many factories. “For a factory, costs of solar installations are close to $1.00-1.20/W,” she says. Mandalay Yoma plans to work on at least eight C&I projects in 2018. Benjamin Frederick, Project Manager at Myanmar Eco Solutions (MES) adds the sector is attractive, although there is a lack of regulation regarding feeding energy into the grid, or subsidy support. The company plans to work on an industrial rooftop in Yangon in 2018, in addition to extending its 58 kWp rooftop PV plant on an island near Myeik, to 317 kWp. Sunlabob Renewable Energy Ltd, which also works in the off-grid sector, is one of the most active companies in the C&I sector to date, having installed the country’s first and second grid-connected commercial rooftop solar systems both in Yangon – 117 kWp at Junction City, and 92.6 kWp on a garment factory.

Image: Myanmar National Electrification Project

Government reluctance

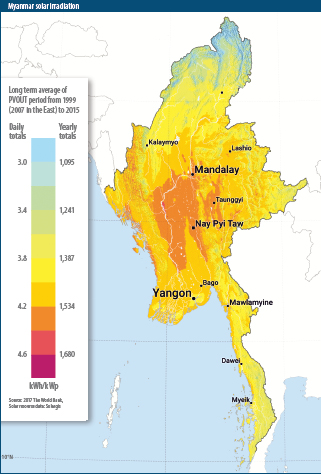

Overall, Bui Duy Thanh, Principal Energy Economist at ADB, says Myanmar represents a 26.962 GW solar energy opportunity, particularly due to its high solar irradiation levels (see map, p. 37). Despite this, a big challenge in kick-starting the utility-scale sector exists. According to a Ministry of Electricity and Energy Presentation held last May, there is a planned utility-scale PV project pipeline totaling 1.5 GW (see table below).

Work is said to be underway on the first 50 MW phase of a 220 MW project, however the company involved, Green Earth Power (Thailand) Co. Ltd, failed to respond to interview requests and information is thin on the ground. Robelus says that while some progress has been made on two utility-scale plants – 300 MW and 220 MW – both are “facing some challenges.” She adds, “In one case the land acquisition is ongoing and in the second case progress is a bit more advanced.”

Frederick says MES has formed a joint venture with asset manager EAM Solar to develop and invest in large-scale solar plants, and that a memorandum of understanding was signed last October to develop a solar power plant with the Ministry of Industry. He did not release details, however. Sources say there is an overall reluctance by the government to invest in these projects. “If private players demonstrate it can work technically, the government will come around,” they say. Frederick adds, “Security of investment is putting many investors off, especially as the government has demanded all future PPAs be signed in MMK – not USD.”

The policy environment is expected to improve over the next two years. At the Myanmar Green Energy Summit, held last August, U Aung Myint, general secretary of the Renewable Energy Association Myanmar (REAM) said the government is reviewing the NEP, to improve and align it with the current situation.

| Project | Installed capacity (MW) | Location (Region/state) | Remarks |

| Nabuai and Wandwin | 300 | Mandalay Region | MOA (Memorandum of Association) & PPA |

| Minbu | 220 | Magway Region | MOA & PPA |

| Shwe Myo | 10 | Nay Pyi Taw | MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) |

| Sagaing and Mandalay | 880 | Sagaing and Mandalay Region | MOU |

| Thapaysan | 100 | Nay Pyi Taw | MOU |

Source: Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy

Sunshine behind the clouds

Despite the policy issues and technical challenges, like extreme weather and grid connection, the general consensus is that solar opportunities in Myanmar are significant. As Gallery says, “Myanmar is a hot market,” with lots of interest by international companies in entering it. Frederick adds, “Myanmar needs energy. Solar is cheaper than all thermal sources, i.e. gas and coal. Solar construction is also a few months, compared with five years for building a coal plant… The barrier is integrating intermittent power plants into the grid, [for] which the solutions too are well documented from other countries.”

Overall, with companies and organizations like Mandalay Yoma and Lighting Myanmar actively working with the government to establish strong policies and formal energy frameworks, the road to solar will be built on a solid foundation, and the realization of the country’s 26 GW solar potential should be a positive one.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.