A team at Idaho National Laboratory has created a new type of electrode, which it says could be used to lower the process costs of large-scale hydrogen, potentially allowing the energy to compete with conventional fossil fuel driven processes used in industry.

In certain areas of hydrogen production, electrolysis can already compete with fossil fuel driven steam reforming, as such processes are difficult to scale down to smaller applications, and have high emissions.

The Idaho National Laboratory researchers state, “Although hydrogen is already used to power vehicles for energy storage and as portable energy, this [their new] approach could offer a more efficient alternative for high-volume production.”

In their paper, the snappily titled 3D self-architectured steam electrode enabled efficient and durable hydrogen production in a proton-conducting solid oxide electrolysis cell at temperatures lower than 600°C, published in the journal Advanced Science, the researchers describe design and production of highly efficient proton conducting solid oxide electrolysis cells (P-SOECs). The cells operated efficiently for more than 75 hours at temperatures lower than, you've guessed it, 600°C.

Popular content

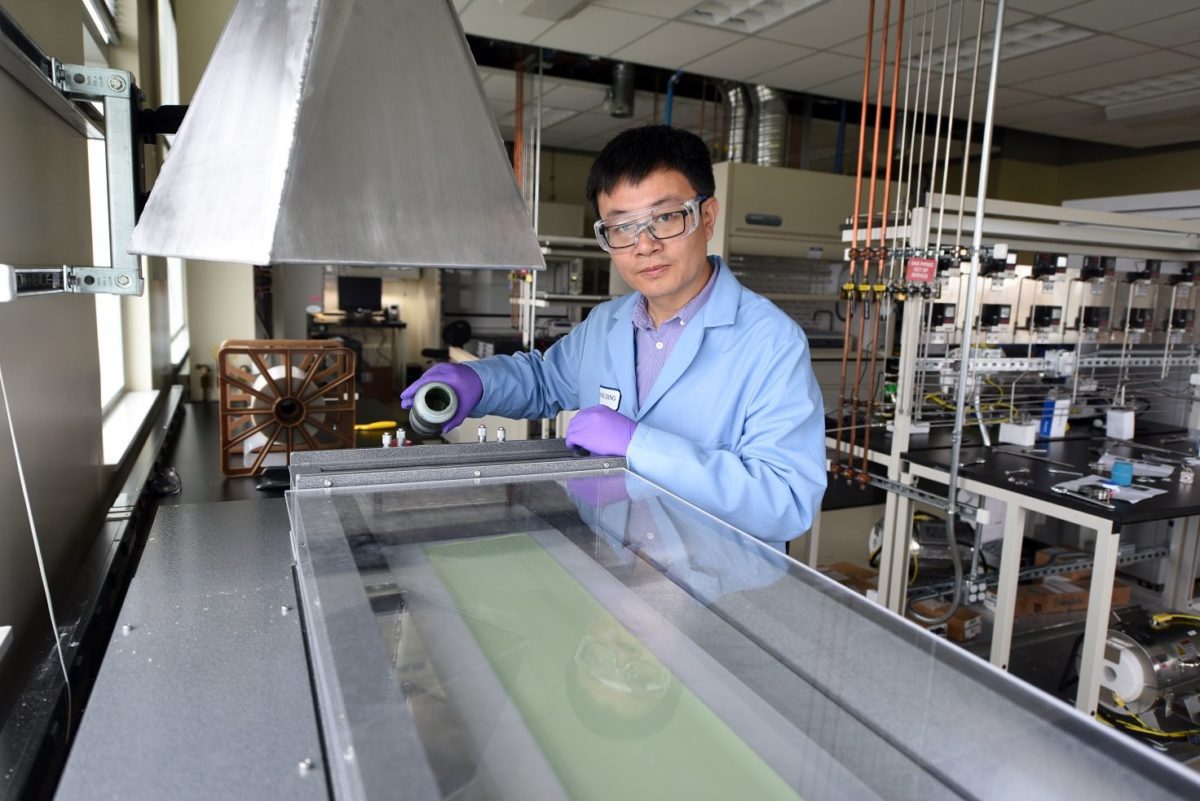

Key to the performance, according to the researchers, was the development of a ceramic steam electrode. “We invented a 3-D self-assembled steam electrode which can be scalable,” says Dr. Dong Ding. “The ultra high porosity and the 3-D structure can make the mass-charge transfer much better, so the performance was better.”

The electrode was created using a woven textile template, which is placed in a precursor solution and fired – burning away the textile and leaving behind a ceramic version of the structure. When placed into a solid oxide electrolysis cell, the team observed bridging between the strands in the ceramic textile, which they say should improve performance and stability.

Cells incorporating the new steam electrode were able to perform efficiently at 600°C, and the researchers say there is potential to bring the temperature even lower. Typical SOECs currently operate at temperatures above 800°C, so the new cell could significantly reduce the amount of energy needed to produce hydrogen. The researchers also point out operating at lower temperatures would allow for the removal of several expensive heat resistant materials in the cell design, further reducing costs.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

3 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.