From pv magazine, December edition

Last month, after a long period of careful consideration, solar salesperson Li Yumin finally made his determination to accept a job offer from an auto parts company. Previously, he had worked for a mid-sized solar module manufacturer located in China’s Jiangsu province.

Li made the move with great reluctance, as he had devoted himself zealously to the PV industry for several years previously. But it was a decision driven by forces beyond his control. And only one week after making the big decision, Li is thinking again.

Li had experienced around four months in a solar market in which struggles abounded. Since October, his company, due to the dim future, had started to downsize and lay off employees in an attempt to cut costs.

“My company had recovered and had good business from the middle of 2017,” Li explains. “Before this May, everyone believed we would have a prosperous year in 2018, like we had previously in 2017. But everything changed on May 31.” The day, which now requires little introduction to solar industry insiders, saw the release of the 31/5 policy changes by China’s central government.

Li’s explanation as to why he made the difficult decision to step out of PV is telling, and not unfamiliar to solar veterans in other parts of the world: “Market demand along each link of the entire [solar] industrial chain has dropped sharply and very quickly since June – including for our module products. Sales decreased greatly, and layoffs are merely a matter of time. Furthermore, I did think that the industry was influenced too much by governmental policies and we are too weak to walk by ourselves.”

Central planning

What is more or less unique to China is that the country retains a high degree of central economic planning. This means that the policy of the Chinese central government impacts on industrial development more than in almost any other major industrial country. And sometimes Chinese policy can change so fast and so dramatically, that it goes beyond industry expectations and the influence of those seriously involved.

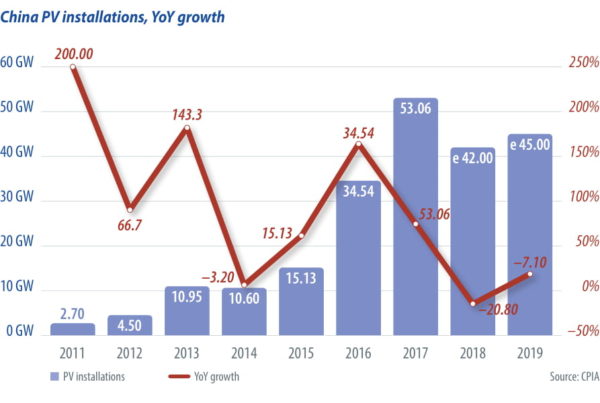

Largely the result of good market settings and a supportive policy environment, China’s PV industry achieved a remarkable installation record of 53 GW in 2017. This trend continued through the first half of 2018, and analysts expected further growth for the full year. However, things changed rapidly after May 31.

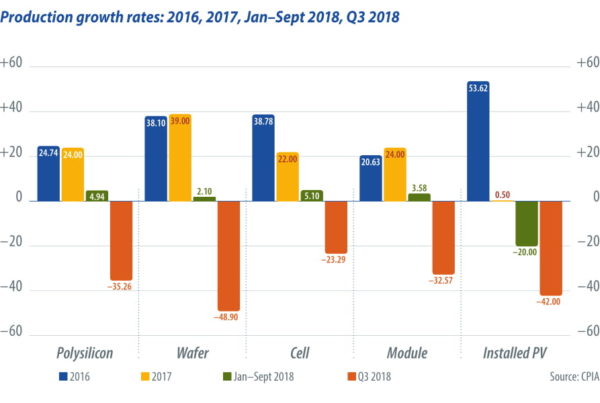

Data from the China Photovoltaic Industry Association (CPIA) show that the production output of polysilicon, PV wafers, cells, and modules recorded similar growth rates in H1 2018 as they had in 2017; but dropped sharply after June (see graph on p.22), as the 31/5 policy began to bite.

When initially announced, it was unclear what precise impacts the 31/5 policy would have on the supply chain, but one thing was certain for all: that this policy represented a profound change for China’s solar industry. It was speculated that it would result in the direct reduction of China’s total PV market by about 30% – and being the world’s largest PV end market, impacts would be felt right around the world.

The policy changed the entire industry so greatly that it was considered an abrupt brake or even “human-made car crash,” in the words of an official from CPIA immediately after it was published.

Looking into the possible motivations for the 31/5 policy, the eager mood of China’s government to reduce the cost of PV market subsidies is clear. Costs of the solar program had grown quickly, and payments due accumulated to a simply enormous amount of money. However, applying the brake so suddenly hurt the industry and caused chaos right across the Chinese solar supply chain.

With the subsidy gone, planned projects had to be financially reevaluated. Most of them were now viewed as unviable, and eventually cancelled. Signed contracts between module manufacturers and their distributers had to be reconsidered, and many of these deals were postponed indefinitely, resulting in a number of bankruptcies. In turn, module manufacturers cancelled cell orders from their vendors. This then expanded to the upstream segment, and then the entire industry was infected with the 31/5 malaise.

Considerable inertia

In October, the CPIA released its Q3 2018 installation data. To most observers’ surprise, it didn’t make for entirely grim reading. New PV installations in Q3 reached 10.21 GW, with 4.89 GW for distributed PV and 5.32 GW for ground-mounted PV. This was much higher than the most pessimistic predictions after the 31/5 announcement. However, the growth rate dropped sharply, as expected, and based on the current situation, total PV installations for 2018 will come in at between 40 and 45 GW. This represents a decline of around 20% or even less – much less severe than initial estimates of a 30% or greater retraction – and is testament to the considerable inertia the solar sector had built up over the previous two years. Financial results echo the decline.

A study of 33 listed PV companies of China’s A-share market, including listings on both the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, showed that almost all financial results posted by companies involved in solar went south in Q3 2018. This is especially evident in net profit results. Only 25 of the 33 reviewed achieved net profit at all, and all of them recorded year-on-year (YoY) decreases, with rates of decline varying between 5.77% and 59.88%.

The profitability result was due largely to declines in sales volume, but also because of the drop in unit prices. Even after several rounds of rebounds, the stock prices of most PV companies are still much lower than pre-31/5.

For former solar salesperson Li, his company started to lay off employees after several months struggling in the wake of the 31/5 announcement. Somewhat ironically, once he decided to leave the industry which he once loved, the government intervened a second time.

Signs of hope

On November 1, Chinese President Xi Jinping convened a high-level meeting with entrepreneurs from China’s major private enterprises. At that meeting, President Xi reaffirmed the importance of private enterprises to the country and committed to continuing government support. The next day, China’s National Energy Administration (NEA) hosted a meeting with major PV players, and delivered some good news. First, the NEA said it was assessing whether to increase the previous PV installation target, a part of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan from 2016. The original target for PV installations of

105 GW by the end of 2020 was surpassed several years early. The new potential target was proposed at between 250 and

270 GW by 2020.

China’s cumulative PV installations stood at 165 GW by the end of Q3 2018. Based on this, and as was later clarified soon after by the NEA, this means there will continue to be 40 to

50 GW of solar installations to be realized in each of the following two years.

The second piece of good news from the meeting is that the NEA formally committed to ongoing subsidies for PV through 2022, though the subsidy will very likely be reduced each year. The abrupt government brake of 31/5 started to look more like a gentle slowdown.

The NEA also confirmed that there will be no restriction on PV projects that can be developed without subsidies, at least in principle. However, such projects would be dependent on successful application for grid-connection. This places more authority with local grid administrators, which will now have a bigger role in deciding on PV project approval.

The NEA also stressed that the government-led “Top Runner Program” and poverty-alleviation PV projects would continue in 2019, and likely account for a bigger proportion of the total installation quotas for that year.

When asked to provide an estimate for Chinese PV installation in 2019, the first response is to hesitate. This is much the same reaction that Li had when assessing his own personal circumstance. It is not clear whether the commitments made by the NEA will become detailed, executable policies – and whether they can be used as the basis for investment decisions.

The NEA commitments clearly send the right signal, but they must become a reality, not just a cordial gesture to comfort those in PV during a difficult time, for solar to regain its footing.

The core issue remains: There are insufficient funds available for the government to pay for existing installations, let alone new capacity. It appears that either new funds must be collected or made available, or the price of PV power must become genuinely competitive with other energy sources. Only then can a clean bill of health be given to the PV sector in China, and its long life assured.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Solar PV is being installed today in Mexico and India at around 3c US per kwh, using modules manufactured in China and shipped across oceans. Can’t it be installed at similar prices in PV’s home market of China, without any subsidies needed?

The article is disappointingly thin. A key plank in the May reform was decentralisation: provinces are now expected to manage solar growth, and in particular to hold no-subsidy auctions. Claiming that China is still a “centrally planned economy” obscures or denies this major policy shift. What are the provinces actually doing? They are the size of large European countries, so administrative capacity is not likely to be a problem.