From pv magazine 10/2021

January 2021, California: A major global developer in Mexico calls the STS U.S. office, experiencing excessive module power degradation and seeking field services to identify and mitigate the issue. The module supplier for this portfolio is among the largest in the world and, thanks to a trusted relationship, is supplying most of this developer’s module needs in Latin America. This time, however, the module quality is falling short of expectations, and the developer has had to deploy additional resources to closely monitor module performance and keep the degradation rate in check. This represents unexpected costs and threatens long-term financial returns for investors.

August 2021, California: For more than a year, STS has been monitoring the solar energy market for activities related to the allegations of forced labor affecting the industry. The Withhold Release Order (WRO) issued in June 2021 is now being enforced by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and a large U.S. utility-scale developer has just been notified by its supplier that its module supply is being detained at the border. This comes as a surprise to the U.S. developer, as it has spent millions of dollars on a critical supply of solar PV modules that may never make it into the country, putting its entire solar asset portfolio at risk. The developer is left with no tangible contractual recourse and is now urgently looking for other suppliers to bridge the difficult procurement gap.

The module purchase agreement is usually the first recourse when events do not go as planned. Cases like these are, fortunately, still relatively uncommon in the PV industry. Nonetheless, the strength of a purchase agreement is revealed in the stress cases just described. Small contractual details negotiated upfront often make a meaningful difference in how these cases are resolved.

Quality assurance

Take the example of the portfolio of solar projects in Mexico affected by a lower-than-expected quality of delivered modules. The contract was not unlike previous, similar contracts; modules even went through an extensive inspection process during manufacturing. Lenders and developers had grown comfortable over previous projects about the inspection firm and the contractual language.

However, the inspection was not performed by an ISO17020-accredited inspection body, and the contract stipulated the use of the manufacturer’s Quality Control Plan (QCP) during manufacturing. The use of the manufacturer’s own QCP is, of course, ideal for them, since they decide on the quality level that they will ultimately deliver. In most cases, the modules delivered are of acceptable quality, and the developer can focus on the next project to be developed.

However, in this case there were traps. The QCP was authorizing up to seven cells with soldering defects on a single module. Soldering defects may reduce the performance of the module in the field, increasing the series resistance, and/or reducing the photocurrent. These defects may also cause hotspots with potentially catastrophic consequences if not kept in check during operations. Today all modern manufacturing lines have electroluminescence (EL) tools capable of identifying such defects. A qualified (accredited) inspection body can prevent them by following three main steps.

First, companies must ensure that the EL tools are properly calibrated before manufacturing. A qualified inspection body will verify the EL tool settings during preproduction inspection, and ensure that EL images are not blurry or too dim to identify defects.

Second, they must verify EL images coming out of production lines. This is done by selecting a subset of the production lot and performing preshipment inspections on samples before releasing the lot.

Thirdly and maybe most importantly, special attention should be paid to the details of the quality requirements stipulated in the purchase agreement. Negotiating these requirements is tedious and requires a lot of attention to details and a lot of experience.

It is a common hidden trap, for instance, to start the negotiation of these requirements too late in the process, when prices and other contractual elements have already been agreed upon. Knowing that the buyer will not walk away from the deal at this late stage, we have seen some manufacturers trying to impose their own QCP, or requesting the right to modify the QCP at any time, unilaterally. This risk is exacerbated in the “sellers’ market” conditions that we are observing today.

To avoid this, STS recommends starting the discussion on the requirements as early as possible, and ideally during the on-boarding process of the potential supplier. It is also recommended to start the negotiations with a thorough set of requirements sufficiently protecting the buyer, and the use of the industry standard STS-STD-PVM1:2018 as a basis for the negotiations.

STS’ experience, for instance, is that most QCPs do not thoroughly describe some elements specified in STS-STD-PVM1:2018 – for instance, what happens in case of identification of non-conforming products. The requirements should also avoid the main technology risks and be adapted to the latest technologies. Many draft requirements are copy-pasted from previous projects, and do not consider the specificities of the products.

As an example of this contractual detail, the emergence of multi-busbar or multi-wire technology presents specific risks to the buyer, which should be correctly captured in the requirements. One such risk is associated with soldering defects. It is simply more difficult to solder multi-wires compared to three-, four- or five-busbar layouts. The previous example of the portfolio in Mexico is here a good illustration.

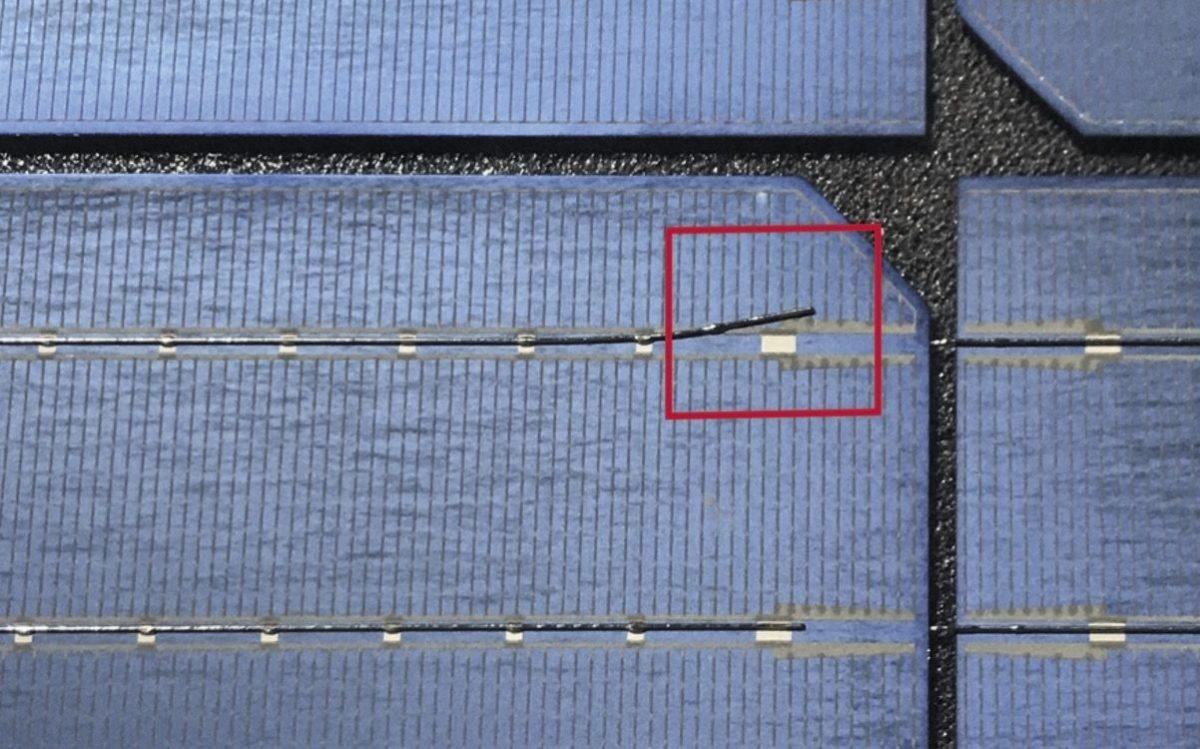

Tree-shaped cracks

Another example is the increased occurrence of “tree-shaped cracks,” a cell crack branching in several directions. This type of crack can lead to reduced performance and create hotspots. Multi-wire technology has a higher likelihood to create crack indentations at the edge of the wire, often branching in at least two directions. The small contact area of the wire with the cell (circular cross-section) creates a stress concentration, sometimes exceeding the fracture threshold of the material.

In a Q1 2021 project, STS had the opportunity to analyze EL images taken at the end of the production line and after shipment on the same modules. Small microfractures, which were hardly visible on the EL image, had propagated into larger branching cracks. Most manufacturers are aware of this challenge and are working on solutions generally referred to as “segmented ribbons,” where some segment of the wire is flattened to reduce the stress at the edge of the cell. Others, unfortunately, opt for a reduction of the quality level in their own QCP to maintain the manufacturing yield.

Another quality-related hidden trap in purchase contracts is the stipulation that the inspection firm should be selected by “mutual agreement.” At first blush, mutual agreements may sound reasonable in a purchase contract. However, this language effectively gives the manufacturer the opportunity to self-select the inspection firm. They may for instance select inspection firms which are not ISO17020-accredited, opening the door to potential conflicts of interest. The buyer should be the sole decision maker on which independent inspection body will conduct audits and inspections.

Supply chain transparency

There is a renewed focus on module supply chains in 2021 – highlighted in the second example raised. In this case, the developer requested authorization to perform an audit of the supply chain of the manufacturer long before the facts. This audit was not accepted by the manufacturer.

This situation is still developing, and the solution is not as obvious as in the first example. The Hoshine-focused WRO took many in the U.S. industry by surprise. Developing a sustainable supply chain – one that is resilient, bankable, cost-effective, socially, and environmentally responsible– is an effort-intensive, long-run process.

Yet, it is STS’ belief that the wider PV industry would benefit from more transparent supply chains. The purchase contract is a good document to make explicit requirements in terms of transparency and to encourage partnership between buyer and supplier. It is recommended, for instance, that purchase agreements secure the right of the buyer to audit the supplier per international standards, such as ISO9001 and ISO28001. Not having the right to audit the supplier is a “hidden trap” that may create a blind spot for the developer, with some potentially damaging consequences.

About the author

Frédéric Dross received his Ph.D. in semiconductor device physics from Telecom ParisTech in France. Dross has been working in PV for more than 15 years, initially in cells and modules R&D for imec in Belgium and Hanwha in California. He then served as the head of the module testing business at PVEL/DNV GL and as VP technologies Americas for DSM. Since June 2020, Dross has been working as VP of strategic development for STS, the global leader in PV module inspection.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.