From pv magazine 05/2022

According to the latest statistics, Portugal installed 572 MW of new solar PV capacity in 2021. Installations include both small- and large-scale PV systems supported via several policy schemes. For example, the country has installed micro and mini PV systems that are remunerated by fixed feed-in tariffs (FITs), although this policy has now been replaced by a self-consumption scheme.

This scheme differs from net-metering in that installed systems do not receive credits for surplus power generation, but instead are allowed to sell excess power to the grid in accordance with electricity market tariffs (pool prices). The policy also allows new installations of up to 250 kW that receive FITs, although the installation of such systems is typically capped each year to account for only a few megawatts of new capacity.

Regarding utility-scale PV, most of Portugal’s large-scale solar parks were installed under the former FIT regime. The Decreto-Lei n.º 76/2019 legal framework introduced in June 2019, set up two routes to market: auctions and direct agreements with grid operators. The latter is widely referred to as the merchant segment of the market, meaning investors sell solar power directly to an off-taker via a power purchase agreement (PPA). Official statistics indicate this is the strongest part of the country’s PV market.

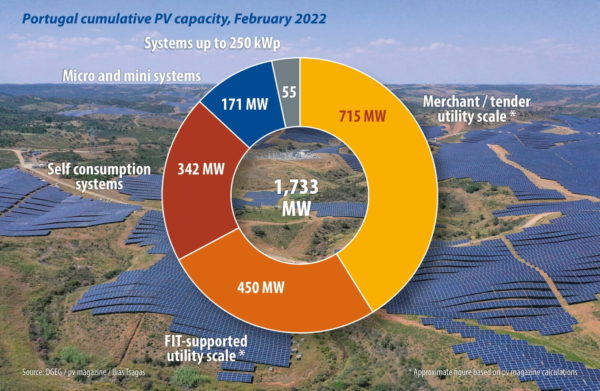

Portugal’s office for energy and geology (DGEG) says that of the 1.73 GW of cumulative capacity, 342 MW stem from self-consumption systems. About 171 MW are micro- and mini-solar installations, while 55 MW are small systems, sized up to 250 kW each and supported by FITs. The remaining capacity comprises utility-scale plants installed via the expired FIT regime, or through the new tender and merchant programs.

The DGEG told pv magazine that it does not have any specific information about these market segments. However, examining the DGEG statistics from the last 10 years and considering the various policy changes that occurred over the same period, it is possible to extrapolate that between 400 MW and 500 MW have been installed under the old FIT regime.

The remaining large-scale installations should thus comprise either tendered projects (very few of which have been installed) or merchant farms. The 50 MW Ourika farm was installed in July 2018 and is said to be both Portugal’s and Europe’s first merchant solar project.

Tendered projects: Loading

To date, Portugal has announced three tenders, in 2019, 2020, and a last one in April this year which focused on floating PV. The 2019 exercise set a low price of US$0.016/kWh, although that benchmark fell to $0.01316/kWh the following year.

The April 2022 auction, meanwhile, generated negative prices, meaning the pv system offering this bid will pay the Portuguese electric system to generate power for 15 years. It is a hybrid project though that also includes wind and storage; therefore the investor can generate profit from the other elements of their investment.

Overall, the tenders allocated 1.15 GW, 670 MW, and 183 MW of generation capacity in 2019, 2020, and 2022, respectively.

The government has boasted that Portugal's tenders have been a success, helping electricity consumers. Such benefits though will only be felt if the projects are installed. To date, very few awarded projects have been realized and the grace period allowing the projects of the first two auctions to gather the necessary licenses has recently been extended.

The DGEG claims this extension is the result of the Covid-19 pandemic, but market forces have expressed doubts over whether all the tendered projects will be installed. It says the current spike in PV equipment costs and the supply chain disruptions make the most competitive of the tendered projects non-economic to build.

Merchant projects: Queuing

The country's merchant projects are less discussed; however, they are arguably where the country may see a new wave of installations materializing soon.

João Garrido, founder and manager of Lisbon-based utility scale solar consultant Caparica Solaris, tells pv magazine that following the policy framework published in 2019, investors flocked to the DGEG, submitting applications for around 253 GW worth of merchant projects.

According to Garrido, however, the framework was poorly designed, and did not request any kind of financial commitments from investors, which is what led to such a vast number of project applications.

In March 2020, the DGEG stopped accepting new applications for merchant projects due to the pandemic and it has not reopened the process. “I doubt it will reopen it any time soon,” says Garrido, who adds that the key issue is the guidelines for the ranking of the merchant projects that the DGEG introduced last February. Under them, investors were asked to provide additional information by July or October of 2020, which would then determine the rankings.

Since then, Portugal’s grid operators have published two lists, ranking merchant projects relating to the July 2020 deadline. Specifically, Portugal transmission operator (REN) published a list of 78 projects, while the Portuguese distribution operator (E-Redes) ranked 53.

Garrido says the market has still not heard back about the merchant projects that relate to the October 2020 deadline and what is worse, he argues, is that a new law (the Decreto-Lei n. º15/2022) introduced in January 2022, cancels all projects that submitted information to the DGEG in October 2020.

As Garrido says, this is unacceptable because “at the end of the day project developers followed the official guidelines only to see their applications not taken any further due to a change in the law.”

The lucky ones

Francisco Veiga de Macedo, manager of Germany-based WiNRG for the Iberian Peninsula, told pv magazine that the lists published by grid operators REN and E-Redes are all projects ranked together with the DGEG. The DGEG and the grid operators, he said, tried to find the most mature projects, e.g., those that had secured land and were pre-approved by the local municipalities, etc.

Following the publication of the ranking lists, both grid operators entered negotiations with developers about their projects’ feasibility studies. Three things need to be clarified though, said Veiga de Macedo. First, not all developers are invited to negotiate with the grid operators, which are currently only in discussion with the top ranked developers. For instance, REN invited just the top 11 projects, corresponding to 3 GW of PV capacity.

Second, investors have little room for negotiation. The grid operators present them with an offer to undertake a grid feasibility study examining the needs to reinforce the grid. It is the investor who pays for the feasibility study, while further to the study any grid reinforcement expenses are also paid by the investor.

Third, the law introduced in January requires grid operators and investors to reach an agreement within 12 months of the publication of the law. But if this negotiation process takes nine months, for instance, what is going to happen with the rest of the projects that are not yet invited to talk to the grid operators, asks Veiga de Macedo.

One potential solution is that the government will extend the 12-month deadline. He agrees but adds that the more top projects that reach a deal with the grid operators, the less viable the lower-ranked projects will become. “This is because the grid will be taken,” he said.

WiNRG is not one of the companies listed by the grid operators because it is not a project developer. Rather, it typically scouts the market for projects under development and presents interesting opportunities to the investors it works with. If investors are awarded the projects, then WiNRG will organize issues like project and asset management, etc.

At present, the company is managing a portfolio of around 200 MW comprising six PV farms connected to the Portuguese grid in 2020, 2021, and 2022. All six projects are merchant, meaning they operate based on a mixture of PPAs with a local off-taker and they take part in Portugal’s spot market.

Veiga de Macedo says these projects were spotted by WiNRG before Portugal had a tender regime in place, yet their investor felt confident to move forward given this is a stable European country with an established market and high solar irradiation. “There is not a strong appetite for corporate PPAs in Portugal yet; however, PPAs with an electricity supplier are viable and we are happy to be able to secure some of the few fully licensed merchant projects that were available early in the country,” he says.

Asked about the future of Portuguese merchant PV projects, Veiga de Macedo concludes: “The DGEG has learned from the mistakes made in the past and I’m very sure we will never have again a process like the one we had in 2019. The DGEG will certainly introduce some barriers to the application process to differentiate between the honest, serious investors and the opportunistic ones.”

However, he also expresses doubts about whether the politicians fully support the merchant solar sector. Indeed, politicians sell the story of tenders to the public as a great policy success on the back of the record-breaking tariffs. Such news makes good headlines. But will they dedicate more grid capacity to merchant projects or stick to tenders, even if the latter are never realized? This remains to be seen.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

It’s an interesting article by Ilias Tsagas that provides insights into the challenges of developing solar merchant projects in Portugal.

The main obstacle is the lack of grid capacity, which makes it difficult to negotiate with grid operators.

Another challenge is the short timeframe for negotiation set by the government.

Overall, there are opportunities for developers who are willing to take on the challenges.

Still, it remains to be seen whether the government will support the solar merchant sector in the long term.