When people think of critical infrastructure, they tend to picture rail networks, hospitals or electricity grids. But one of the most essential everyday technologies is sitting in almost every kitchen: the fridge.

Unlike lighting, which can be replaced by candles in an emergency, refrigeration has no easy substitute. When the power goes out, food spoils quickly, medicines lose effectiveness, and livelihoods dependent on selling cold drinks or ice cream are put at risk.

As climate change drives more frequent and severe weather events, the resulting blackouts and brownouts are becoming more common. Grids that were once stable are under increasing strain. The major Iberian blackout that struck Spain and Portugal earlier this year, together with Storm Darragh in the UK (also known as Xaveria in Germany), highlighted the vulnerabilities of even the most developed systems.

In many parts of Africa and Asia, people live with these conditions daily. And as grids in Europe and North America face mounting pressure, their experience is beginning to look less like an exception and more like a preview of the future.

A new standard for weak and off-grid fridges

Recognizing this, the IEC has finalized IEC 63437, a standard for domestic and light commercial fridges designed for weak and unreliable or intermittent electricity supplies, as well as for off-grid fridges designed to be directly powered by photovoltaic (PV) solar panels.

Patrick Beks, Director and Co-owner of the Dutch firm Re/Gent BV, has led much of the work on the document within IEC TC 59, the technical committee that prepares standards for the performance of household appliances. His company grew out of Philips’ former refrigeration R&D labs. “There are a lot of areas in Sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world where reliable refrigeration does not exist,” Beks explains.

IEC 63437 introduces simple classifications. Supply classes show how long a fridge can keep cooling during outages – for instance, four hours on and 20 hours off. Voltage classes indicate the range of fluctuations an appliance can survive, from as low as 30% to as high as 200% of the nominal supply. The standard also prescribes solar classes, representing various supply signals generated by a solar panel.

“It presents information on the power outage a fridge can withstand while still cooling, and the voltage fluctuation it can tolerate. With that label, people can select the right fridge for their region,” says Beks.

The standard also defines test procedures: how quickly a fridge cools down, how long it holds temperature during blackouts, and how it copes with voltage stress. Importantly, it doesn’t prescribe how to build a fridge, only how performance and energy consumption should be measured.

“If you have a generator, how long do you need to run it each day for the fridge to stay cold for 24 hours? Those are the kinds of questions this standard helps answer,” says Duncan Kerridge, a senior R&D engineer, formerly with SureChill, who is now contributing to IEC work.

A major obstacle has been defining what “weak grid” means. “There’s a real dearth of data on supply quality,” Kerridge notes. “There are isolated studies, but drawing a conclusion is difficult because there isn’t consistency.” Governments and utilities often make matters worse by being reluctant to share outage data, fearing reputational damage, he adds.

Yet, as Kerridge points out, monitoring needn’t be costly: “You can put together simple microcontrollers for around GBP 100. The challenge is getting them deployed widely and ensuring they all measure the same parameters.” Beks hopes that introducing the standard will spur more monitoring. “Once the standard is used, it will also initiate investigations in specific regions,” he says.

Grids for emerging nations

While IEC 63437 focuses on appliances, Kerridge is also helping draft a technical report on “developing grids” in a working group of IEC TC 8, which is standardizing power quality. This will define how to assess the reliability of electricity in low- and middle-income countries, a first step towards global consistency. For now, the group is focusing on the basics: whether the power is on or off, what voltage ranges are typical, and which kinds of fluctuations most damage appliances.

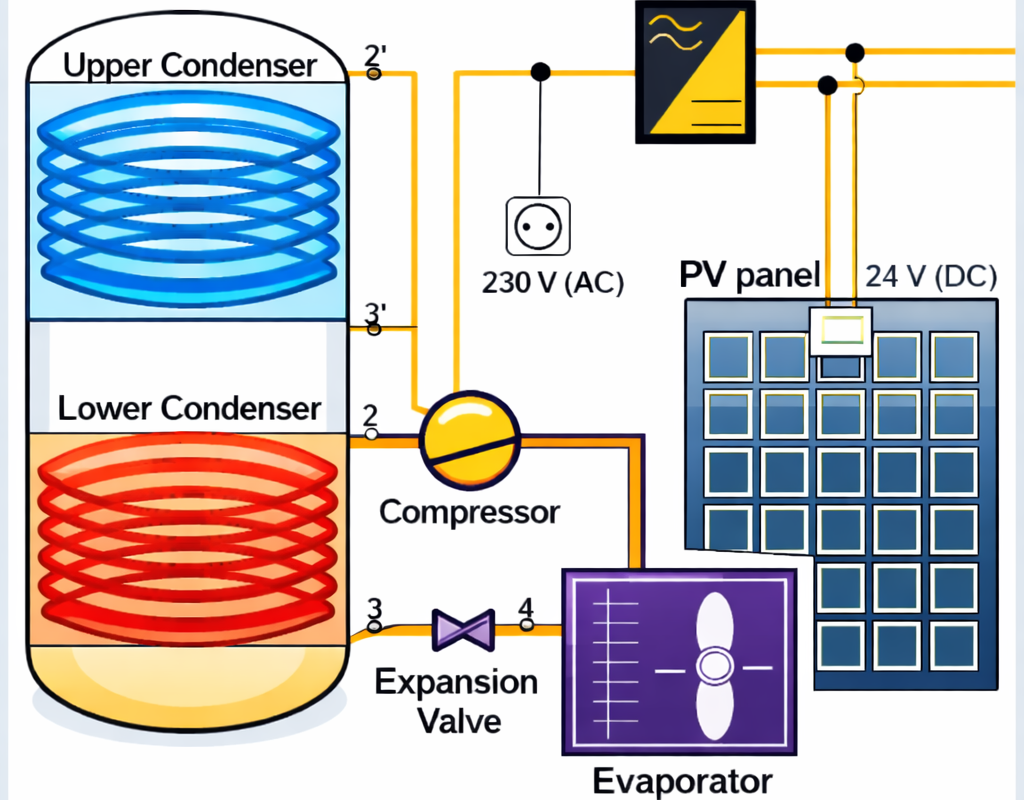

Alongside the standards, researchers are testing new technologies to make fridges more resilient under weak-grid and off-grid conditions. One promising approach is solar direct drive cooling, which powers refrigeration directly from PV panels without relying on external batteries. Instead, thermal storage inside the cabinet maintains cold temperatures at night or during cloudy spells.

Ivan Katic, a senior specialist at the Danish Technological Institute (DTI), leads a Danish-funded initiative exploring how this approach can move beyond vaccine fridges into the wider food cold chain. Scaling up has required new hardware. While the alternating current (AC) market has plenty of large compressors, adapting them for direct current (DC) solar power is difficult. Katic’s team worked with a Danish manufacturer of frequency converters and compressors to develop a variable converter that can run a standard compressor directly from solar panels.

Specialized software then adjusts power consumption depending on how much sunlight is available. “We’ve proved it’s possible,” says Katic. “The converter can adapt automatically, so the fridge keeps running even as supply fluctuates.”

Examples in Kenya and the Philippines

To prove the concept, the project is building demonstration units: freezers for fishing communities in Kenya and fridges for a dairy producer in the Philippines. In Kenya, the challenge is particularly acute: freezing fish requires large amounts of energy, and outages risk wasting the catch. The solution is to integrate saltwater-based thermal storage inside the freezers, maintaining sub-zero temperatures overnight. “The idea is that the content stays cold even when the power dips. That way, the fish is preserved, and losses are reduced,” says Katic.

The project, run in cooperation with the WWF, will test whether the technology can strengthen local fisheries and cut waste. In the Philippines, the aim is to help dairies keep milk cold in rural areas where the grid power is unreliable. Both pilots will provide field data on performance and costs – essential for scaling up.

But commercialization remains difficult. Cabinets with integrated phase-change material (PCM) storage are expensive, and sophisticated converters and software add further costs. At the same time, competition from battery-backed solar systems may undercut the appeal of stand-alone units. “For distributed small-scale systems, it has a promising future, but for larger commercial industrial systems it may be more cost-effective to introduce a local grid that you can rely on,” Katic says. He remains optimistic: “If fridges upscale and costs reduce, it will be a good technology.”

IEC Standards could help as well on the solar thermal tech: IEC TC 117 prepares standards for solar thermal energy plants and is increasingly looking at standardizing solar thermal applications for industry.

Lessons for the Global North

Although IEC 63437 and Katic’s pilots were designed for the Global South, climate change is blurring the line between “developing” and “developed” grids. “The application of weak-grid fridges in combination with smart grids in the developed world is also an expected future trend. The idea is to use electricity when it is available and cheap and not to use it when it is scarce and expensive,” says Bek.

“I don’t know how bad things are going to get with climate change, but if supply signals deteriorate and grids get worse in the developed world, then of course you could use this standard,” he adds. Kerridge agrees. For domestic fridges, simple steps like keeping the door closed during outages can help. But for hospitals and pharmacies, the stakes are higher. “It’s about vulnerability and criticality of the load. During Storm Daragh, my wife’s pharmacy had to replace medicines after a 24-hour outage,” he recalls. The World Health Organisation (WHO) is already taking note. It has its own electronic prequalification system (ePQS) for vaccine fridges on intermittent and solar supply, and, according to Beks, there is interest in aligning future work with IEC benchmarks.

Katic’s work also illustrates what the next generation of solutions could look like: battery-free solar fridges serving fisheries, dairies and small businesses. By combining technical standards with innovative design, researchers hope to make cooling more reliable for everyone.

Author: Ann-Marie Corvin

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is a global, not-for-profit membership organization that brings together 174 countries and coordinates the work of 30.000 experts globally. IEC International Standards and conformity assessment underpin international trade in electrical and electronic goods. They facilitate electricity access and verify the safety, performance and interoperability of electric and electronic devices and systems, including for example, consumer devices such as mobile phones or refrigerators, office and medical equipment, information technology, electricity generation, and much more.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.