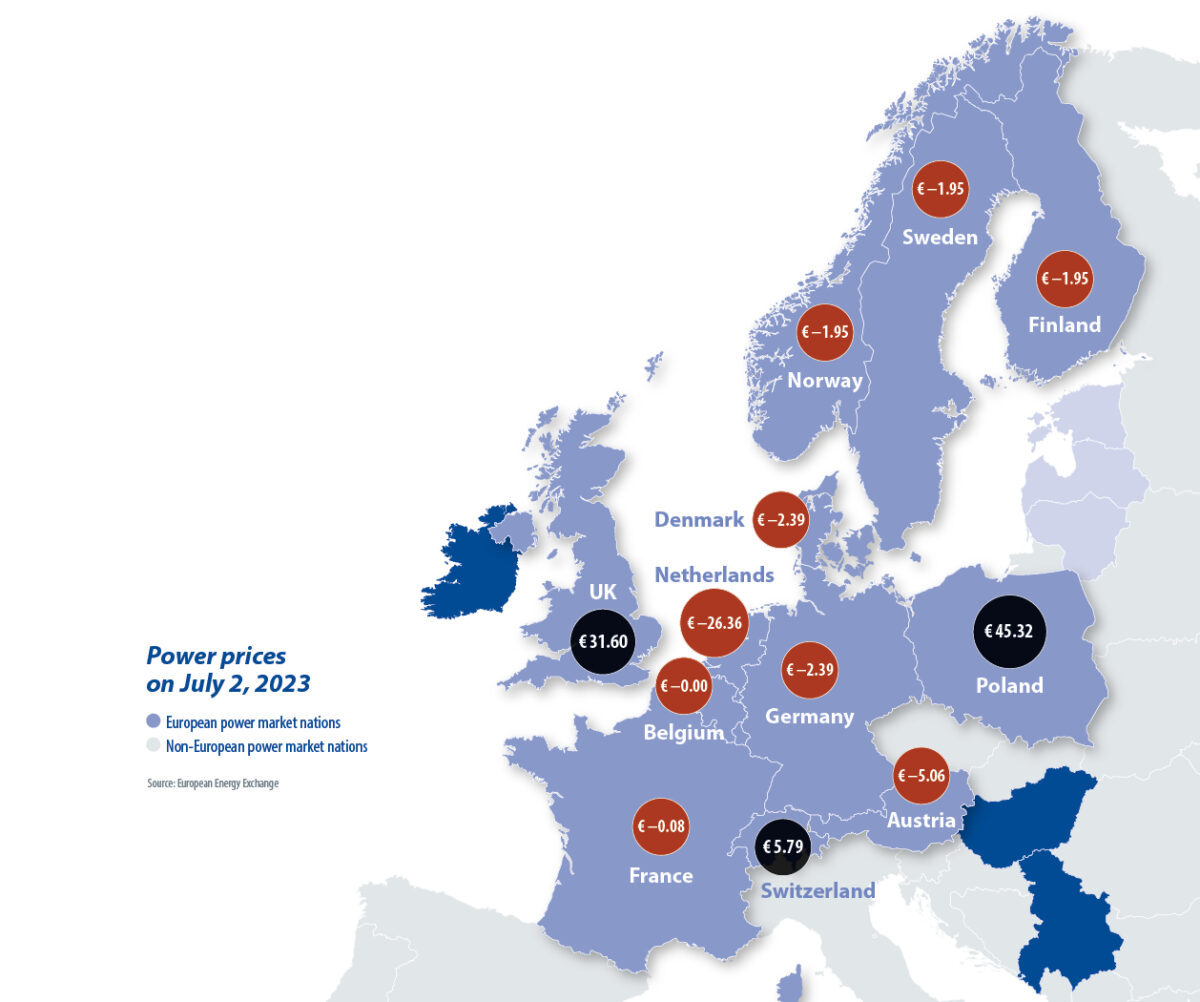

The most extreme situation in European electricity markets this year occurred during the first weekend of July. Europe saw, for most of the day, negative wholesale prices across the whole continent, from Finland to Spain.

Paradoxically, consumers in countries such as Ireland and Denmark are currently dealing with record-high retail electricity prices that are more than five times the average cost of wholesale power. The German government is also considering subsidies to shield its heavy industry from international competition and escalating energy prices. All of these circumstances show an energy system in need of serious reform. Across Europe, the electricity price that end consumers pay comprises the cost of generation, grid expense, government levies, charges, and taxes such as VAT. The approach to taxes and levies varies, with nations including Malta, Bulgaria, and Hungary imposing lighter taxes on electricity than, say, Denmark, which penalizes heavy usage.

The treatment of commercial customers and heavy industry also varies by nation with Germany being highly supportive of manufacturers while Ireland, for instance, is not. All retail electricity prices contain two common elements, however: the cost of electricity generation and maintaining grids.

Price structure

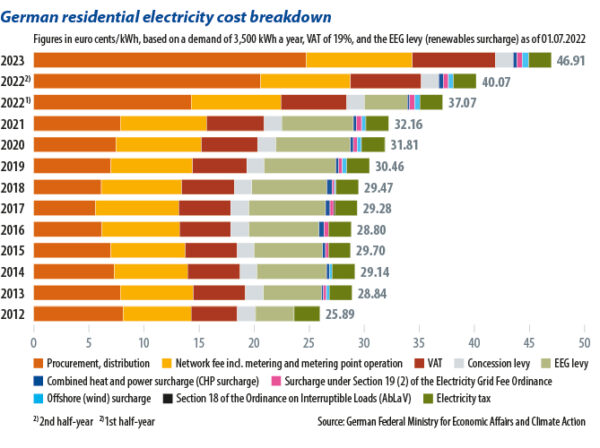

Taking Germany as an example, the average retail consumer paid more than €0.46/kWh ($0.50) in the first half of the year. Those rates were nearly 50% more than what the consumer paid in 2021 and were largely a reflection of the Russian gas crisis. Interestingly, wholesale prices have now come back to 2021 levels of around €0.07/kWh to €0.10/kWh, which begs the question: Why is the German consumer still paying €0.24/kWh just for the generation component of their electricity?

The answer to that question is that they are doing so because many German utilities hedged their power purchases at the top of the market last year, when extreme gas prices and problems in French nuclear saw European power prices hit all-time highs. The good news is that the customer will gain the benefit of the current lower wholesale prices, going forward.

The same cannot be said for the grid costs which make up the other major component of electricity bills. Grid expenses across Europe, as a rule, are lower than generation costs, at an average of €0.06/kWh in the EU. In the first half of 2023, German grid costs were €0.095/kWh, putting them at the very upper end of European costs.

Grid expenses have surged by 50% over the last decade. The substantial investments required to connect new renewables plants and transport their energy, largely account for this trend. Complicating matters, system stability costs are rising exponentially, especially when systems are overloaded or grid bottlenecks occur.

Supply dynamics

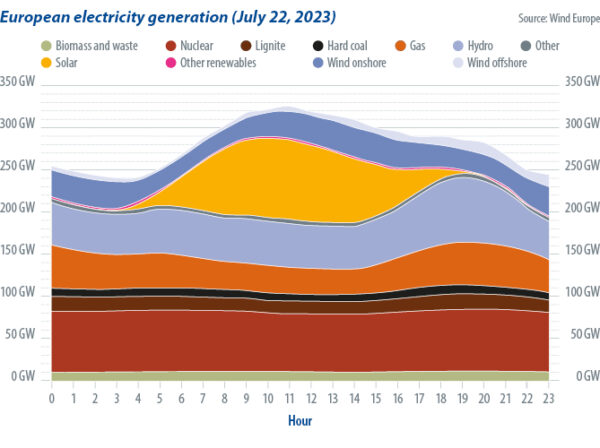

Europe currently has an installed renewable energy fleet of 690 GW of generation capacity, comprising 255 GW of hydropower, 225 GW of wind, and 209 GW of solar. On a good weather day, that is enough to meet the electricity needs of the whole of the market. The good news is that there are now many days when 50% or more of Europe’s power needs are met by renewables. If you add nuclear to the mix, there are many days when 75% of Europe’s power needs are met by low-CO2 electricity. This is particularly the case at weekends, when peak European demand is around 320 GW and there is lots of solar electricity in the system.

This large volume of renewable energy means that the weather now determines the power price. When there is an abundance of sun, wind, and rain – as there was during the first weekend of July – power prices tumble. When there is not a lot of sun or wind, power prices increase. All generators have to monitor the weather so that they can optimize their power generation assets.

The best generation facilities are those that can be easily ramped up and down, like the many types of modern natural-gas plants. When required, the ones that are ramped down first are those with fuel costs, such as coal and gas, especially if a generator believes that they will not be able to recover the costs of fueling their power station with the price they receive on the power market.

The most difficult generation assets to manage are the “baseload” power plants, which are designed for continuous operation. Many old nuclear, coal, and gas power stations are baseload sites, along with most run-of-the-river hydro plants. They are very difficult to ramp up or down, let alone switch off, which is why, oftentimes, they accept very low power prices or even negative prices in the market.

Going forward, the economics of these baseload plants are going to be severely tested as the frequency of negative electricity prices and volatility is only going to rise, fueled by the addition of 70 GW of solar and wind power this year alone, with a similar amount expected next year and the year after. This also poses a financial challenge for new clean energy generation, as renewables plants could potentially also earn zero income during sunny or windy days.

Decarbonization pathways

Rapid decarbonization requires deep electrification of the energy system, starting with transport, then heating, and, eventually, cooling. Major organizations such as the International Energy Agency believe that this is the best route to net zero – not only in terms of economics, but also in order to achieve the goal at a sufficiently fast pace.

The way forward is to add sufficient renewables and nuclear generation to the system to meet growing demand for electricity and to ensure that the electricity mix is clean. This approach has the added benefit of lowering overall energy demand, as the whole process of creating, transporting, and using electricity is much more efficient than burning fossil fuels.

Despite deep electrification being generally recognized as the best way to decarbonize, most countries in Europe still have customer incentive structures in place which are skewed towards the fossil fuel alternatives. In response, governments are finally putting in place subsidies to incentivize customers to buy electric vehicles and install heat pumps.

However, such policies fail to deal with the major distortion present in the market, represented by the fact that it is still cheaper, throughout most of Europe, to fuel a car with diesel than with electricity, or to heat a house with natural gas, as opposed to a heat pump. The main reason for this is tax policies which favor fossil fuels over electricity.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach and will be critical if we are going to decarbonize.

Starter policies

There are six initial policy steps European governments could action:

- Reduce electricity taxation: It is essential to make electrifying transport and heating economically viable for consumers by reducing electricity costs. This will likely involve a fundamental review of what comprises an electricity bill, with a close examination on how best to optimize the generation and grid elements. More importantly, governments need to review taxation policies by noting that in many European countries, taxes represent more than 50% of consumer electricity bills. That level of tax should be progressively placed on fossil fuel in the form of higher carbon levies.

- Use every unit: Wastage of electricity must be minimized by optimizing demand to coincide with periods of surplus electricity and low prices, requiring smart meters and conducive regulation, especially around the provision of flexible tariffs which enable the consumer to take advantage of periods of low electricity prices. It is also important to ensure that regulatory frameworks are in place to allow any excess electricity to be converted into other energy forms, such as synthetic fuels, that will further help with decarbonization. This will also kick-start new business models to benefit consumers and speed up the energy transition.

- Phase out baseload generation: It is necessary to accelerate the phasing out of baseload fossil fuel plants, with the most flexible generation sites being moved into reserve. This will lessen the number of periods with low and negative wholesale power prices which will, in turn, incentivize the building of replacement clean generation facilities while allowing other, cleaner baseload electricity plants – such as nuclear and run-of-the-river hydro – to continue thriving.

- Facilitate energy storage: All barriers to energy storage development should be removed and consideration should be made to putting in place incentives for flexible generation – some of which may be fossil powered – for what German-speakers dub “dunkelflaute” days in winter when there is not enough solar or wind production.

- Accelerate network expansion: Revise the incentive structure for grid operators, in order to push quick and cost-effective investment into power networks while at the same time increasing the utilization and efficiency of existing networks with new technologies and service structures. This will, in turn, unleash a whole range of new business models, from smart charging for electric vehicles to domestic virtual power plants.

- Provide European oversight: Establish a European institution which would be responsible for overseeing the whole energy transition and for ensuring the most effective path forward for the decarbonization of the European energy system. A key focus would be on enabling close, cross-border cooperation, which is key to keeping costs low and which is, in turn, critical for continued European business and industry success as well as keeping the cost of living low for all European citizens.

Without such reforms, the road to decarbonization will be exceedingly rocky. If these measures are implemented, however, they could enable quick, effective, and economical decarbonization.

About the author: Gerard Reid is a partner at corporate finance advisory Alexa Capital. He has spent more than 20 years working in investment banking, equity research, fund management, and corporate finance, with a focus on the energy transition and the digital energy revolution. He previously served as the managing director of European cleantech research at investment banking group Jefferies & Co.

About the author: Gerard Reid is a partner at corporate finance advisory Alexa Capital. He has spent more than 20 years working in investment banking, equity research, fund management, and corporate finance, with a focus on the energy transition and the digital energy revolution. He previously served as the managing director of European cleantech research at investment banking group Jefferies & Co.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.