From pv magazine Germany

Dark clouds hang over the European solar market, and SolarPower Europe has even spoken of a “perfect storm.”

Module prices have plunged by nearly 30% since January, with utility-scale PV offers hitting €0.11/W ($0.12/W). The solar industry's cyclical nature is resurfacing when the EU Commission and German government plan to rebuild their PV supply chains.

A debate has ignited among industry participants on the need for measures to restrict Chinese module imports, sparking heated debate on social media. Saxony-Anhalt Energy Minister Armin Willingmann, leading Germany's energy ministers' conference, has addressed the problem. They have cited unfair competition and have attributed the “module glut” to a US import ban over forced labor allegations in Xinjiang, China. The belief is that unsellable US stock is flooding European warehouses, driving down prices, and exacerbated by Chinese “dumping.” Potential measures, yet undefined, could include import duties or bans in response to dumping and forced labor concerns.

Cost concerns

However, analysts find that explaining the module price drop solely as Chinese dumping is overly simplistic. Some gauge module supply by comparing export data from major Chinese ports with European installation volumes, despite the lack of official export data from China.

These estimates are subject to short-term fluctuations and will become more accurate with time, acknowledging some inaccuracy in module inventory data. However, on a European scale, this discrepancy amounts to just a few gigawatts. For context, the German Federal Ministry of Economics anticipates a European Union photovoltaics market of 70 GW to 100 GW by 2023.

In June, analysts at Rystad Energy first observed module accumulation at the Rotterdam port, initially projecting a year-end module inventory of 100 GW. However, Marius Mordal Bakke, an analyst at Rystad, revised his year-end module inventory forecast in an interview with pv magazine. He noted that market adjustments led to significant order reductions. Examining module export data from China to Europe, he observed inventory levels stagnating at around 40 GW, suggesting that manufacturers respond to demand signals from wholesalers and project developers.

The 40 GW accumulation is the result of market dynamics in Europe. The Ukraine conflict and energy crisis drove many homeowners to invest in photovoltaics, heat pumps, and electric vehicles in 2022. Concurrently, ongoing pandemic disruptions in Chinese manufacturing capacities hindered production ramp-up. Wholesalers frequently struggled with deliveries, often leaving new customers underserved. Orders were declined, and existing customers were categorized based on priority, leading to a subsequent market downturn.

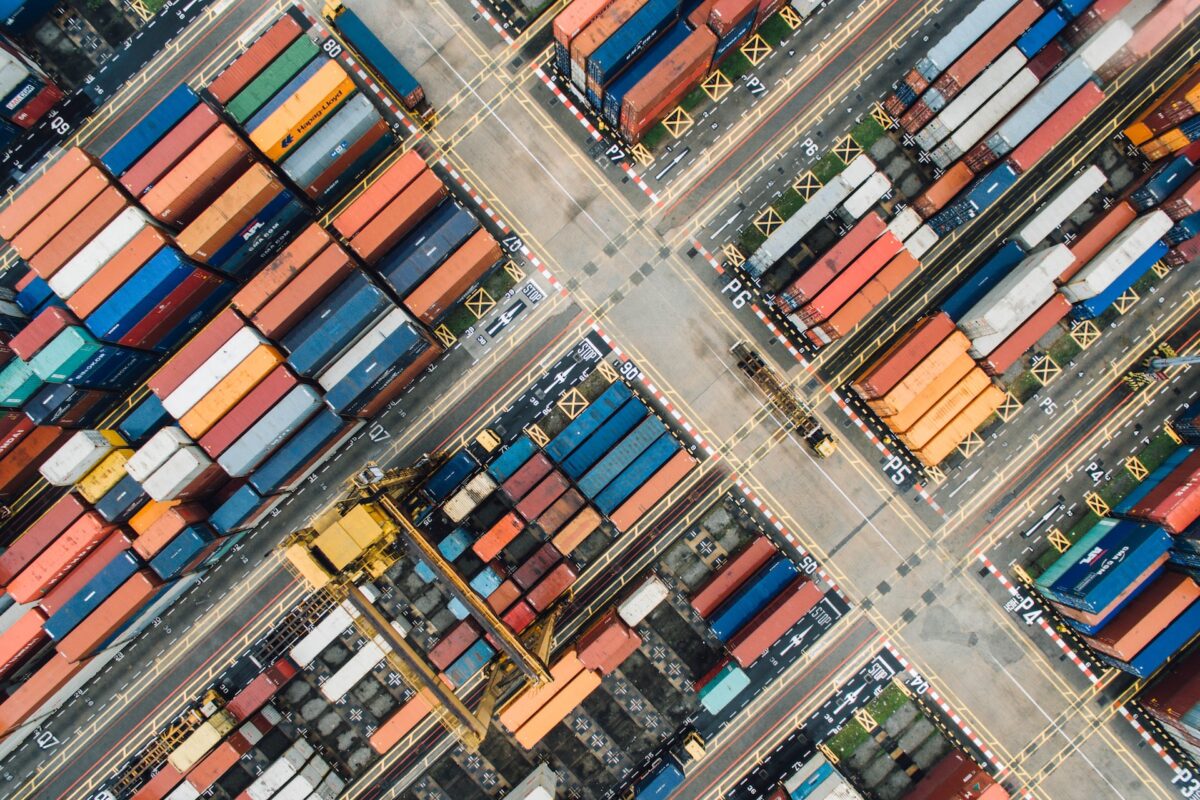

“Retailers across Europe saw their inventory running low and ordered massively to be able to deliver to their customers immediately,” said Edurne Zoco, an analyst at S&P Global. At that time, the wholesalers' sales representatives were fighting for every container from China, as well-known wholesalers unanimously reported to pv magazine.

As a result, module manufacturers' sales teams repeatedly increased their demand forecasts, prompting manufacturers to expand production capacities. The market shifted from being a “distribution market,” where scarce goods were rationed, to a “buyers' market,” where price became the primary concern, and demand could be met.

Taking lessons from 2022, wholesalers, mindful of not disappointing customers again, stocked their warehouses generously. Any excess that couldn't fit in the warehouse remained at the port. During the summer, analysts from Rystad, BNEF, and S&P Global consistently observed a gap between module imports and installations, ranging from 40 GW to 60 GW.

The European market also underwent changes, with energy prices gradually returning to normal levels.

“Rooftop market growth in Europe in 2022 was significant due to the energy crisis and high electricity prices, but this sense of urgency for installations in the residential and commercial sectors has waned as electricity prices came back from record prices,” says Zoco.

Verivox reported that on Jan. 1, the average cost of a kilowatt-hour for new customers in Germany was about €0.44 (§0.47). Since then, prices have consistently fallen, with new customers now paying an average of €0.29/kWh. This trend has a clear impact: as electricity prices decline, the incentive to invest in photovoltaics diminishes.

Additionally, rising interest rates have made financing considerably more expensive. Negative publicity surrounding the Building Energy Act has further discouraged potential solar installations, especially in conjunction with heat pumps.

Popular content

End of the party

Although demand in the rooftop segment remained relatively strong, it did not meet the expectations of manufacturers and many wholesalers during the first quarter, resulting in demand falling significantly short of expectations. An oversupply of modules led to price declines, posing a serious challenge for wholesalers who had purchased modules at higher prices than they could currently sell them for.

Wholesalers who obtained 500 W modules at €0.25/W are now struggling to sell them for only €0.15/W, resulting in substantial capital losses on inventory. This situation has led to some retailers facing financial difficulties, raising the risk of insolvency. To cope with the oversupply, both Chinese module manufacturers and European wholesalers are working to offload their inventory, even if it means selling below value, prioritizing cash flow over profit.

The World Trade Organization's definition of dumping includes not only prices below production costs but also whether manufacturers charge similar prices in export markets as in their home market. Inquiries in China revealed offers for new p-type modules ranging from €0.156/W to €0.164/W, with slightly higher average prices for new n-type modules, ranging from €0.166/W to €0.176/W. The minimum value of €0.11/W likely represents discounted pricing for older PERC modules.

“We have confirmation of distress sales to reduce inventory as well as redirection of some volumes to other parts of the world,” Zoco said.

According to some analysts, the problem of particularly large module stocks is a global one. Zoco, for example, names Brazil as the destination for module redirections.

The widespread transition to TOPCon technology is contributing to the decline in prices for PERC modules. PERC manufacturers are required to switch to TOPCon technology promptly, resulting in the rapid depletion of PERC cell stocks, which are being processed into modules, suspected by both wholesalers and analysts, albeit cautiously. While the process appears plausible, it is challenging to definitively prove.

The swift adoption of TOPCon and Heterojunction technologies is naturally driving down prices for PERC modules. Some manufacturers are enticed by the prospect of “fire sales,” prioritizing the release of capital tied up in modules. Delaying sales could lead to higher losses, although some manufacturers urgently need the funds to remain financially stable.

Chinese manufacturers are also facing a challenging situation, incurring losses due to the ongoing price war. Jenny Chase, an analyst at BNEF, foresees the possibility of bankruptcies among Chinese manufacturers, a recurring occurrence in the cyclical solar industry. The decisive factor in this regard will be internal Chinese demand for modules in 2024 and 2025.

“It is too early to know whether this will have an impact on consolidation at the manufacturer level,” said Zoco.

Wright's Law?

The debate centers on whether prices fall below production costs. Analysts note that most mainstream modules are sold for €0.14/W to €0.16/W in projects exceeding 10 MW. The cost learning curve evaluates industry development, traditionally yielding a 20% cost reduction with production capacity doubling since 1976 when Wattpeak cost $100, maintaining a favorable trend with an outlier in 2008.

As of 2020, global installed capacity reached 774 GW, with mainstream module prices at €0.21/W according to the pvXchange index. With cumulative installed capacity in 2023 at 1,500 GW, post-learning curve costs could be around €0.168/W. While prices may vary due to supply and demand, this suggests that the price decline doesn't seem fundamentally implausible, requiring direct explanations of subsidies or dumping.

Analysts and wholesalers anticipate it may take until the first quarter of the next year to normalize inventory levels. The ongoing debate regarding measures to restrict Chinese module imports mirrors the situation during the 2013-2018 “tariff period.” Many individuals we interviewed, including wholesalers, project developers, and analysts, express doubts about tariffs effectively stimulating European production. Higher photovoltaic product costs could lead to decreased demand, potentially necessitating additional public funding.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Thank you for this very differentiated article and the many sources.

So Rystad has corrected his figures by a whopping 60% downwards.

At 15 cents/Wp and 60 GWp, that’s just 9 billion less in the warehouses.

And the justification for the current accusations that China would deliberately flood the market to destroy the tiny EU manufacturers should now finally collapse.

“No dumping discernible”.

I also like the thoughts on the PV learning curve and the resulting cost reductions.

Translated with http://www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Put me on your information list