It’s no secret that inverter problems are among the most common causes of failure at PV plants, with many needing to be swapped out less than halfway through the term of a 25-year power contract. And while PV modules are frequently subject to intense third-party testing – in addition to standard certification testing – there hasn’t been anything like this so far for inverters.

That is, until May of this year, when PV Evolution Labs (PVEL) released its Inverter Scorecard, the first edition of what it plans to make an annual publication. This scorecard reveals the results of testing of inverters from 12 manufacturers that participated in PVEL’s Product Qualification Program (PQP).

Top-line results from the scorecard were fairly shocking: one-third of products failed the company’s arc fault test, 21% failed the damp heat test, and a quarter failed the humidity freeze test.

These test results showing high failure rates support experience in the field, and as it turns out, there are many ways for inverters to fail. The Inverter Scorecard identified no less than seven major types of inverter failure, looking at everything from interconnection problems to catastrophic, dramatic failures such as fires and explosions resulting from arc faults.

And while it is more often the case that components wear out and underperform than plant managers need to call the fire department, these can have impacts on a plant’s return on investment.

Certification vs. reliability testing

In terms of the products that failed PVEL’s testing, all were certified to UL and IEC standards, which involved tests. And this points to an underappreciated distinction: Certification testing only determines that products meet certain minimum quality and safety standards. This is entirely different than reliability testing, which attempts to predict how products will perform over their lifetimes.

PVEL’s PQP involves many of the same tests, but applied to a much more severe degree, including many more cycles in climate tests like damp heat, and in some cases combined. And while there is no test that can perfectly predict how an inverter or any other component will last over time, by subjecting components to these stresses over and over again, PVEL and other third-party testing companies attempt to simulate time in the field.

But these tests are not all that PVEL does. Through the Factory Witness portion of its PQP, it also conducts production audits in factories. There is a lot to be learned through this process, but chiefly through monitoring production, PVEL is able to ensure that products being tested use the same bill of materials that the company has specified, and avoids manufacturers supplying what have come to be known as “golden samples.”

“We want the products to be representative of what the commercial products will be that go to the distribution lines and to the field,” said Michael Mills-Price, head of the inverter and energy storage business at PVEL. “And if connectors are improved or other things have been done to it to make it more of a golden sample, that’s just not applicable to what you would see when you’re buying these products normally.”

Popular content

Along the way, PVEL has revealed that it has found variations in quality not only between manufacturers, but also among the different product lines made by those manufacturers and the products made in different nations.

PVEL’s inverter scorecard reflects this. The three top performers in each test were spread across a number of different manufacturers, and while products by some manufacturers such as Delta showed up as top performers in a number of different tests, these top performers were often different models, and no one inverter model aced all the tests.

Mills-Price notes that this difference in performance between products may be due not only to quality, but also to design choices, with the design of different inverters reflecting different priorities.

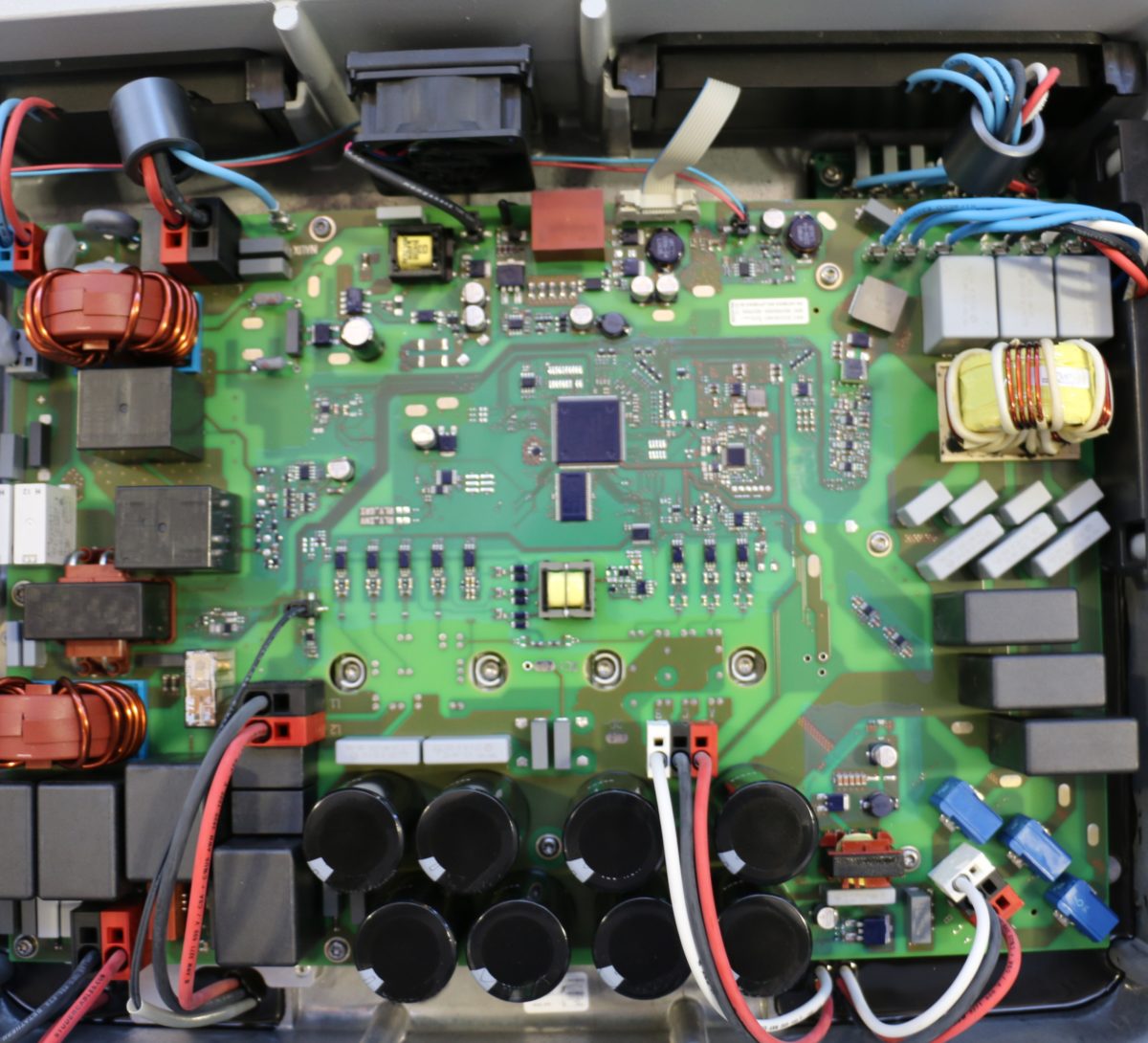

Image: PVEL

Demanding testing

Despite being the most common point of failure in a solar project, inverters have not received anywhere near the level of scrutiny that modules have to date. Mills-Price says that this is likely a result of the relatively higher cost of modules, which remain the single most expensive component in a PV system.

But with module prices falling and becoming a smaller portion of overall system costs, this shifts the attention to the factors that determine system performance, and not just the performance of any one component.

Part of this disconnect may be due to inverter makers providing an overly rosy picture of the reliability and maintenance needs of their products. A study cited by PVEL shows that the actual cumulative cost of inverter ownership over four years is much higher than the cost estimates provided by manufacturers. But even in the best of cases, most inverters only hold 10-year warranties, unlike modules, where warranties have moved into the 25-year+ range.

And there is always the factor of short-term versus long-term interests. Developers and EPCs are the ones that select the components for solar projects, but after they sell them, they are not responsible for the long-term performance. Instead, it is the asset owners, and in some cases even the long-term financiers who end up footing the bill when projects have problems.

PVEL Chief Commercial Officer Tara Doyle says that either way, there is a need to inform the buyer community about the risks. “This year’s inverter scorecard –it was partially about education,” explains Doyle. “People don’t know what they don’t know.”

PVEL’s inverter PQP is still much smaller than its module PQP, and Doyle says that there still isn’t a lot of data because it is not yet being demanded by developers. However, she sees signs of this changing. “They are starting to see firsthand the returns on their projects when an inverter fails,” Doyle says. “The long-term life of the system is what the industry is starting to focus on.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Sadly, this article presents no list of what inverters passed or failed, neither does the PV Evolution Labs website. Sure you can download a report but it only discusses the testing process.

The information on what products pass & don’t would be a VERY HANDY THING to have would it not.. otherwise what IS the point 😕

Hi Steve,

I can appreciate your frustration but PVEL operates a strict non-disclosure policy as it is only able to carry out such exercises with the participation of inverter manufacturers, who volunteer products for assessment on condition of anonymity. The point of such exercises is to observe such data as failure rates, which helps inform decisions about whether, for instance, tougher industry standards should be applied to inverters.

Pls can you give the names of the top performers?

Hi Levi,

Unfortunately I guess PVEL does not name the best performing products either (see my response elsewhere in this comment section), presumably because that would make it easier to narrow down the companies whose products suffer the highest defect rates.