From pv magazine, October edition

To paraphrase views recently expressed by some market players, when it comes to windproofing, “EPCs build quick and move on”, while “OEMs shop for the least onerous wind tunnel advice,” and “buyers don’t want deals to fall through in the due diligence phase.” Technical advisors, meanwhile “aren’t bold enough to give bad news, or “don’t understand this field.” It’s hardly a positive picture – so where do we go from here?

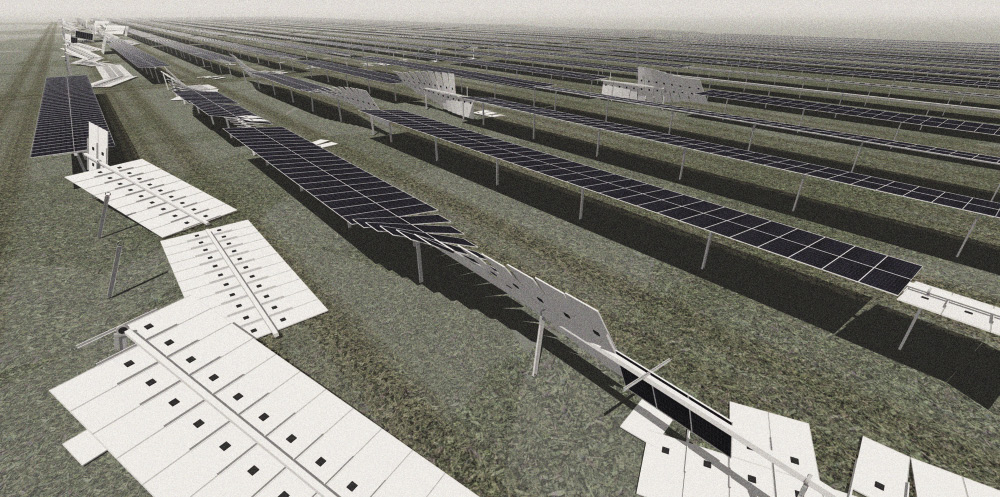

Wind damage can apply to fixed ground-mount, rooftop and carport PV installations – but in this article I’ll focus on the topic of PV tracker systems. Consulting to owners and investors, I’m often at work reviewing PV structure designs, setting specifications, and finding root causes when things have gone wrong. It would be easy to join in with the accusations after seeing just how dramatically things can fail in the field, but instead I hope you’ll find these reflections constructive.

Aeroelastic effects

The classic technology scale-up risk has come true. Trackers performed well when they were small, so we supersized them, only to find that other emergent properties have changed the game. Aeroelastic effects, being the interaction and coupling of fluid (aero) and structural (elastic) forces, are not new in civil or aeronautical engineering. However, aeroelastic effects are safely ignored in many engineering applications and this was the historical backdrop for PV tracker design. Nowadays some single-axis tracker architectures, particularly with a horizontal wind stow, are so slender and torsionally flexible (twisty) that they can self-destruct from aeroelastic vibration before design wind speeds are reached.

The consensus is that aeroelastic instability needs to be prevented rather than controlled. This should have a fundamental impact on tracker architecture: its length, the module arrangement, its stiffness, damping, and stow strategy must be balanced to prevent the onset of aeroelastic instability. I have counted four public webinars addressing this topic in the last six months – manufacturers are clearly keen to show that they acknowledge the concern. Now the test is to see how designs might change.

Trackers must evolve

Have you heard comments like “don’t go above one module in portrait” or “horizontal stow isn’t safe?” Well, the physics are more complex, and the possibilities are actually quite flexible. Length, module arrangement, stiffness, damping and stow strategy are all interrelated and offer endless permutations of tracker architecture – some will be stable and others will be unstable. In terms of the practical reality though, it’s true that the jump in aerodynamic loads between one module and two modules in portrait is not linear, and requires some very careful tuning of all the other variables to achieve aeroelastic stability at the same wind speeds.

After dramatic failures of some types of architecture, we’re expecting to see the evolution of some product lines while also seeing claims about wind design speeds revised downwards.

Site conditions

For many sites around the world, national standards provide a reasonable basis for characterizing extreme wind speeds. But in cases of complex terrain, unusual climates or sites outside developed economies, standards may not be reliable enough. In these more complex situations, and with wind damage no longer viewed as “that’ll never happen to our project,” wind measurement campaigns and specialist wind simulations certainly have their place. And we’ve seen some uptake of this in practice.

In other situations, a wind study could lead to capex savings. At a site statistically proven to have low extreme wind speeds, or shown not to experience the most extreme winds from due east or west directions, this could actually broaden your purchasing options and lead to structure cost savings.

Set standards

It has been said, and Everoze agrees, that codes and standards are not sufficient to use as standalone references in purchasing specifications. At best, these standards include nonprescriptive pointers towards extra dynamic and aeroelastic studies. At worst, they let users off the hook altogether.

Structural codes in the United States might be the first to introduce new requirements, but this could involve some suboptimal compromises and they are not due until 2022. In the meantime, those buying or financing PV tracker projects will need to set their own technical requirements and do their own detailed design checks.

Call for dialogue

Critical views can easily become unproductive unless there is active engagement between industry stakeholders. Even in the pressurized situation of investigating structural failures, I’ve been encouraged by the respect and understanding that can be built when we have a good conversation between different parties.

Let’s not wait for more failures before we increase the dialogue between manufacturers, engineers, owners and investors.

About the author

Simon Hughes is a partner at Everoze, a European technical and commercial energy consultancy that specializes in renewables, storage and energy flexibility. He has 14 years of experience in the engineering of structures and renewable energy consulting. Unusual experiences like cable car aeroelastic design, wind turbine structure analysis and foundation retrofitting projects have been useful since he branched into solar power. Based in the United Kingdom, he has gigawatts of PV project references and global solar experience in northern Europe, Iberia, Australia and South America.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Bonjour

Hello

WE have designed a new concept for solar tracker innovative and disruptive we solve most of the current problems of the industry.

Our tracker has only 2 fondation point for 90 panels and has outstanding wind performances not sensible to galopping at wind speed higher to 50 m/s 3s 10m and with natural damping ratios higher to 15%

We have many prototypes running

WE ALREADY HAVE THE INTEREST AND BAKING OF KEY PLAYERS LIKE NEOEN AND TOTAL-EREN, BOUYGUES ES INTERNATIONAL, GÉNÉRALE DU SOLAIRE.

You are welcome any time to visit us

Contact:

Jerome Tordo

Jerome.tordo@icloud.com

+33 673729351