Not long after China imposed restrictions on travel between provinces, problems began to accumulate in PV module factories throughout the country. Let’s start with personnel issues.

Workers from provinces affected by the pandemic who wanted to return to factories after Chinese new year on January 25 were not allowed to do so because of the imposition of a 15-day quarantine period.

Those who were able to return were, in many cases, several days late due to transport restrictions. Some factories recruited temporary staff to bridge the gap. However, most of those temps lacked adequate training. The result was an abnormally high defect rate on production lines in the following weeks.

As a consequence of the travel restrictions and lack of personnel, supply problems were immediate. Trucks queued at checkpoints while drivers had their temperatures measured and traffic jams caused by roadblocks were a normal occurrence in February. Consequently, the supply chain was interrupted and the reserve materials stored before the start of the new year holiday were depleted. Manufacturers would not return to pre-crisis production rates until the end of March.

On the other side of the world, the impact of non-existent, or at best minimal production, was of course immediate. Lack of module supply had a devastating effect for some developers. For instance, in Germany, where fixed tariffs are tied to strict grid connection dates, the long term economic viability of projects was put in serious jeopardy. That situation prompted various developers and engineering, procurement and construction companies (EPCs) to accept older modules or panels made by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). As a result, module supply contract clauses relating to independent quality assurance were scrapped. For example, modules might be accepted which did not meet agreed frame dimensions or cable lengths suitable for tracker systems.

Another example concerned a developer forced to accept panels from three OEMs which resulted in 12 bills of material (BOMs), hampering material traceability and any evaluation of the manufacturing processes involved. In that instance, some of the BOM combinations were not listed in the certification construction data forms. The variety of BOMs could explain why some of the modules showed a high susceptibility to potential induced degradation (PID) or light and elevated-temperature-induced degradation (LeTID), or why post-stabilization degradation (light-induced degradation) varied greatly. To complicate matters further, in a few cases it was necessary to deal with lack of cooperation by manufacturers who refused access to factories for our engineers, despite no Covid-19-related restrictions being present in the provinces concerned. At the other extreme, however, were manufacturers who facilitated our transit through control points by providing official invitation letters.

Popular content

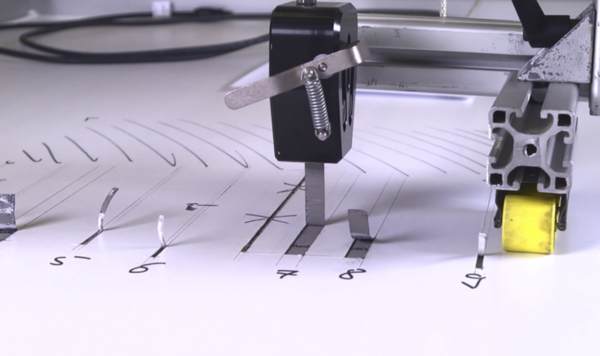

It goes without saying the situation greatly complicated our day-to-day work, which became an obstacle course to the implementation of applying control measures in record time. Those measures included remote monitoring of production through video cameras assigned to factory personnel with little knowledge of production lines. Such a solution should be regarded as a necessary evil in an extreme situation when external auditors could not gain factory access. On the other hand, in those cases where modules had already been manufactured and production monitoring was no longer possible, flash-lists of the products were used to select samples to be sent to our laboratory in Suzhou. Module samples included low, medium and high power modules in the same class, from different batches and with different failure patterns visible under electroluminescence.

What can we learn from all this? First of all, quality control during the crisis was critical to avoiding changes in material selection and manufacturing processes not covered by contract arrangements. Secondly, rapid decision-making about critical activities; the knowledge we have gained from factories in the last nine years; and the flexibility shown by our customers enabled us to perform successfully during a unique situation. That said, a contractual framework between manufacturer and buyer which expedites the implementation of some of our core recommendations for quality assurance could have avoided some of the challenges imposed by some manufacturers.

Last but not least, as a preventive measure for future such pandemics, module supply agreements should cover the following points: A comprehensive elaboration of the concept of pandemic as a force majeure; agreement production supervision will take place, without notice day and night to increase control over non-approved materials; and express indication manufacturers cannot deny access to auditors unless a force majeure clause has been invoked.

By Asier Ukar

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

A much more important lesson the developers and customers worldwide should learn from this pandemic is that it is very important to spread the manufacturing of goods to different countries. The best solution is to produce more modules locally, even if it is at a higher cost. Not more than 30% should be sourced from a single country. An all out effort should be taken up immediately to redistribute manufacturing activities and related supply chains to different countries and regions. Ultimately, the economic cost we pay will still be cheaper and more equitable in the long run. What the society world over are paying now is many multiples of all what we we apparently have saved over many years in the name of cheaper goods coming from far away places. The current situation is doing so much harm to all nations. Wider technology development and its local exploitation is severely hampered in the current supply chain model.