China is still pushing solar PV and renewables at home, and also taking the renewable energy, power generation, and transmission technology and expertise it has gained to a wide range of foreign markets. It is another great export opportunity for China and armed with massive funding from its development banks, it is fast becoming the leading protagonist in electricity markets in various regions of the world.

This includes Africa, where a staggering 70% of the population south of the Sahara Desert lacks access to electricity. But it also includes Europe, where China is keen to tap Europe’s expertise in integrating solar PV and wind resources into its electricity grid.

Liebheit’s insights into China

China’s dominant position in a wide range of electricity markets around the world was one key message delivered by Andreas Liebheit, President of Heraeus Photovoltaics, to a packed audience at Conexio GmbH’s Business Breakfast at Intersolar Europe 2018 on June 21. Heraeus is a leading photovoltaic materials supplier to Chinese PV manufacturers, so the company has a very good sense of what is happening in the Chinese PV industry and the Chinese economy in general. So while the notice from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), National Energy Administration (NEA), and Ministry of Finance (MOF) will put a severe dampener on Chinese PV demand in 2018, the medium and long-term outlook remains very strong for renewables, including solar PV.

Liebheit opened his presentation with a look at China’s electricity generation. Just six years ago in 2012, annual power generation amounted to about 5,000 TWh. With China’s continued double-digit economic growth, this figure is currently in the range of 6,600 TWh per year and is expected to increase by 10% in the next two years. By 2040 power generation in China should reach 10,400 TWh.

Looking at where this power is coming from, the picture is changing rapidly: In 2012, roughly 80% of China’s electricity came from fossil fuel sources, with coal-fired power plants providing the bulk of the nation’s power. By 2040 renewables will have secured up to 60% of China’s electricity mix, a truly amazing turnaround given the amount of power that’s involved.

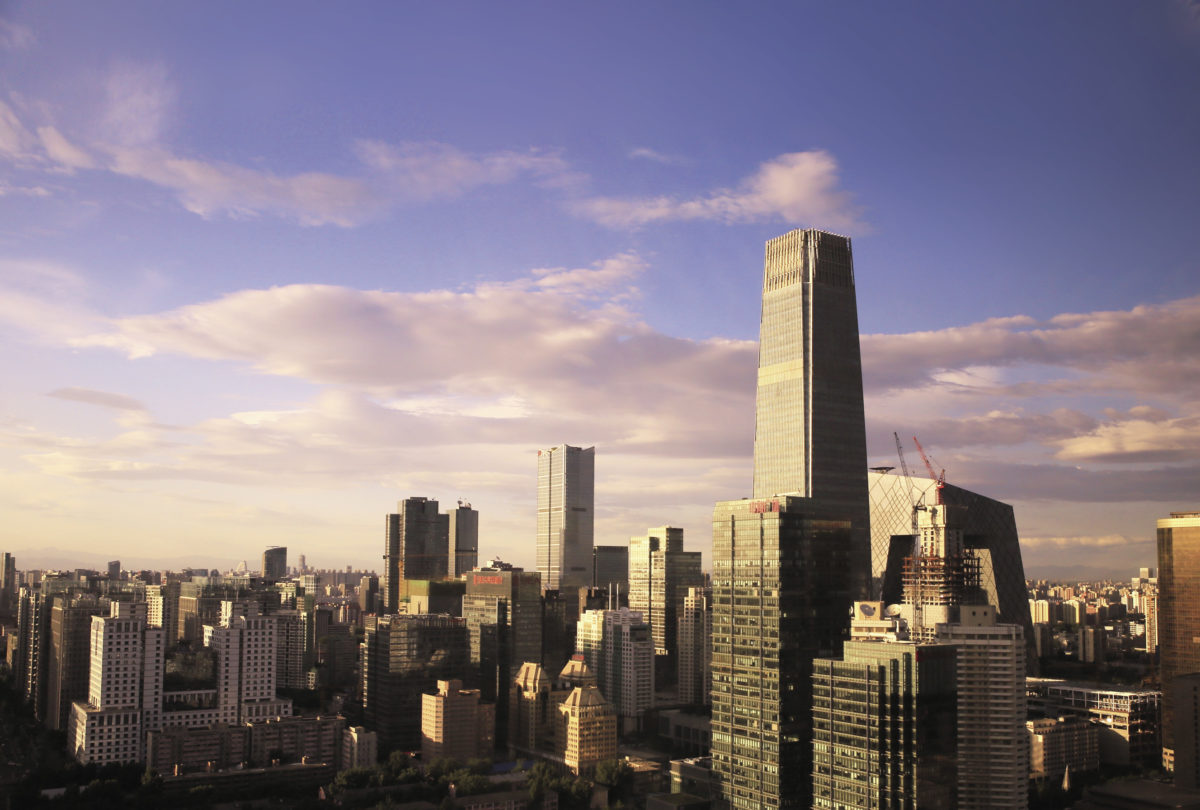

“Blue Sky” days in Beijing

While most China-watchers and indeed the global PV community are focused on China’s central government, local authorities are doing their part to hasten this shift from dirty to clean power. Liebheit points to Beijing, which within a span of just four years closed down the five coal-fired power plants in its region and successfully shifted from coal-fired power generation to gas-fired plants.

While coal supplied almost 40% of Beijing’s electricity in 2012, this is now well below 10%. Of course, gas is not really clean, but as Liebheit remarks later in his presentation, the construction of ultra high voltage (UHV) DC transmission lines from Western China to Beijing will bring clean PV and wind electricity from remote western regions of China (where such renewable energy is plentiful and cheap) to China’s demand centers along the eastern seaboard. The UHV DC line in question has a capacity of 200 kilovolts and runs for 6,000 km from China’s western regions to the Beijing metro area.

For the people in Beijing, who in 2014 formed a “Blue Sky” initiative to combat the rampant air pollution in the city, the outcome has been 226 blue sky days in 2017 compared to only 176 such days in 2013. The annual average concentration of fine particles (PM 2.5 in micrograms per cubic meter) has been reduced by 35% from 89.5 micrograms/m³ in 2013 to 58 micrograms/m³ in 2017. Local initiatives also play a very important part in boosting e-mobility in China, which is by far the world’s largest EV market with approximately one million electric vehicles. Cities like Beijing and Shanghai have basically banned new combustion engine vehicle registrations, so that EVs are the only viable option for people looking to get a new car.

Massive export opportunity

But back to the world stage and the massive export opportunity these domestic initiatives engender, as Liebheit puts it, “China would not be China if they did not export these accomplishments in a big way. Already today the Chinese have acquired a leading technology position in various sectors. China is investing massively in renewable energy worldwide. The sum of $360 billion by 2020 is the key figure. In 2017 alone China invested $44 billion in the renewable energy sector outside China.”

While Liebheit focuses on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as the main platform to put these funds to work in countries outside China, there is also the Global Energy Interconnection (GEI) initiative championed by Liu Zhenya, the former head of State Grid, China’s largest transmission utility and the world’s second-largest company after Walmart in the 2017 Fortune 500 list. In its June 7 “The Big Read” piece entitled “China eyes role as world’s power supplier,” the Financial Times (FT) provides details on GEI. According to the FT, “Designated a ‘national strategy’ and championed by Xi Jinping, China’s President, the [GEI] initiative feeds into China’s most ambitious international plans – to create the world’s first global electricity grid.”

The killer app UHV

UHV technology plays an important part in this plan and has been “dubbed the ‘intercontinental ballistic missile’ of the power industry by Liu Zhenya,” according to the June 7 FT article. Calling UHV technology the ICBM of the power industry also highlights the economic and security dimensions of this international “power play,” be it on the back of BRI or on the back of GEI. As Liebheit pointed out at the Conexio event, China’s current Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) puts other Asian countries in first place when it comes to China’s infrastructure investments overseas (with a 30% share), followed by Africa (with a share of about 25%), Latin America, and Europe (including Russia).

According to the FT article, “Chinese companies have announced investments of $102 billion in building or acquiring power transmission infrastructure across 83 projects in Latin America, Africa, Europe, and beyond over the past five years, according to RWR Advisory [a Washington, D.C.-based consultancy]. Adding in loans from Chinese institutions for overseas power grid investments brings the total to $123 billion. Throw in all power-related Chinese deals overseas, including investments and loans to power plants as well as grids, and the number almost quadruples.”

And if UHV technology is the ICBM in all of this, then one key objective is to utilize UHV technology to transport PV and wind electricity from regions such as Western China to cross-border demand centers further afield. For example, as Liebheit points out, to take clean power from Western China to demand centers in Russia in exchange for oil and gas deliveries. Or to take hydro power from a massive dam in Africa, where clean energy can be harvested and transported to major population centers far from the dam (Liebheit highlights the 3 GW Mambilla hydroelectric plant in Nigeria being built by a trio of Chinese companies for what is expected to amount to a $5.8 billion investment).

Opportunities in Africa and Europe

China is by far the biggest investor in Africa’s electricity grids and as Liebheit observes to the amusement of the audience at the June 21 breakfast event, “Africa is now fully part of the Silk Road,” which in its modern incarnation carries the initials “BRI” and is chiefly Beijing-backed. Then again, Africa requires $93 billion annually (according to Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic) to upgrade its infrastructure to cope with a population that is growing at a rate of 25 to 30 million people annually. If China is the only country ready to mobilize massive resources to meet this challenge, then other countries outside Africa should not criticize China for taking the initiative, even if the outcome could be an electricity grid in Africa largely controlled by Chinese institutions.

Europe is also on the BRI and GEI map, but at least within the European Union there is not a huge gap between electricity demand on the one hand and the supply of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution on the other. In such a situation of relative luxury, European countries have been sensitive to Chinese power companies seeking to acquire stakes in strategically important electricity players in Europe. Liebheit highlights the Chinese attempt to acquire an indirect stake of 20% in the German transmission system operator (TSO) 50Hertz Transmission GmbH, an acquisition that is not seen favorably by Germany’s government.

For Liebheit, the Chinese interest in 50Hertz also points to another motivation driving Chinese energy players. They can see their country moving to solar PV and other renewables and are keen to learn from a country like Germany, where wind and solar PV already form almost 50% of the country’s power generation fleet. 50Hertz has been at the vanguard of this renewable energy integration in Germany and possesses valuable know-how, which could prove helpful in China’s transition to an energy system built on renewables (and in other regions of the world as well, particularly BRI countries).

Technology leadership

China is tapping into renewable energy expertise and technology around the world and its focus is not only on solar PV and wind power. Nuclear power and hydropower are of strategic interest to China as well and the transition to a low carbon electricity system also means tapping into other important areas, be it digitalization, smart grids, energy storage, e-mobility, and other sectors undergoing electrification. China regards all of these sectors as strategically important, also to tackle the “middle income trap” that has prevented many rising economies from becoming more than just a low-cost workbench for run-of-the-mill products. All of the above sectors are there for the taking, so to speak, and China wants to secure technology leadership in as many of these areas as possible.

Finally, there is the geopolitical aspect and China’s push to expand its sphere of influence, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, but also in emerging markets like Africa and Latin America. By gaining a substantial footprint in these markets’ power grids (and in some cases like Brazil and the Philippines even outright control), China can gain influence, both politically and economically.

As Andreas Liebheit pointed out at Intersolar Europe, Chinese PV companies are already active in over 50 Belt and Road countries. As more Belt and Road power grids have Chinese owners, this grid ownership can act as a platform, not only to cobble together a regional or eventual Global Energy Interconnection, but also to bring in Chinese PV and other technology suppliers to realize low carbon energy networks. The stakes are high and in this broader context, the recent NDRC, NEA, and MOF notice is probably just a blip on the radar, with a range of powerful drivers ensuring a bright future for the Chinese PV industry and the Chinese energy industry in general.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

“…2012, annual power generation amounted to about 5,000. ….. By 2040 power generation in China should reach 10,400 TWh. …. In 2012, roughly 80% of China’s electricity came from fossil fuel sources, with coal-fired power plants providing the bulk of the nation’s power. By 2040 renewables will have secured up to 60% of China’s electricity mix, a truly amazing turnaround given the amount of power that’s involved.”

This means that in 2012 China produced roughly 4,000TWh from fossil fuels, and that 2040 China still will be producing 4,000TWh from fossil fuels. No, not a turnaround.

“The UHV DC line in question has a capacity of 200 kilovolts ..” The capacity of a power line is measured in watts not volts. China is building multiple HVDC lines from the West, not one. The typical voltage is 800kv; power capacities go up to 10 GW.

A powerful writing about Chinese vision to face global electric energy shortage situation. Both private and public sector of China combined have taken steps to invest billions of dollars for renewable energy propagation.

China no doubt now is the most far sighted nation. I support all Chinese role and initiatives taken so far and wish to work with them if I get any scope ever anywhere.

A SLOGAN

March China March,

Build a Carbon-Free Earth!