From pv magazine 12/2019

Today, there is no avoiding the concept of sustainability. This is to say nothing of the fact that individuals and companies cannot openly refuse to act sustainably. But that alone does not really change anything. That’s why we asked our readers – installers, EPCs, consultants, investors, lenders, PV system owners, and other industry stakeholders – how they saw the state of sustainability in the solar and energy storage industries, and what sustainability means to them.

Today, there is no avoiding the concept of sustainability. This is to say nothing of the fact that individuals and companies cannot openly refuse to act sustainably. But that alone does not really change anything. That’s why we asked our readers – installers, EPCs, consultants, investors, lenders, PV system owners, and other industry stakeholders – how they saw the state of sustainability in the solar and energy storage industries, and what sustainability means to them.

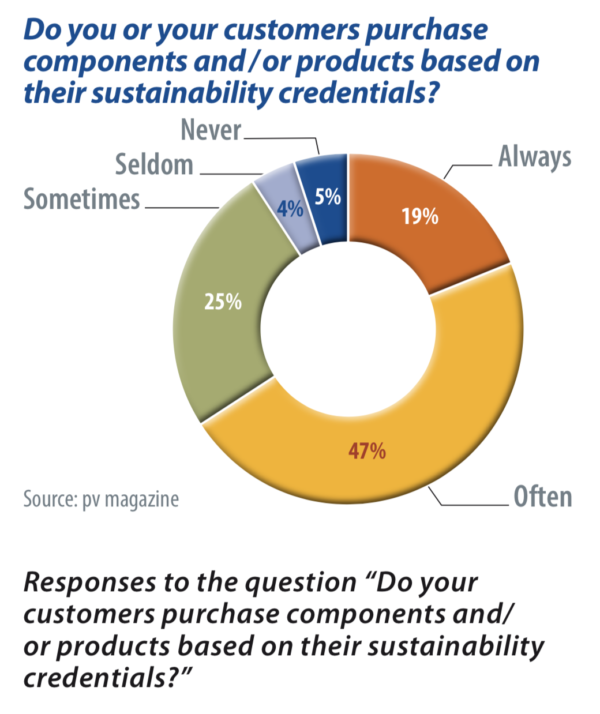

The short answer is: quite a bit. The call to participate in our survey, which appeared for a week in our daily email newsletter, was heeded by 79 people, including 44% from Europe, 30% from Asia, and 15% from North America. Sixty-six percent of the participants in this non-representative survey stated that they or their customers always or frequently based their purchasing decisions on sustainability (see chart below). pv magazine also conducted the same survey for the German market only. The sentiment was very similar among the 274 participants in this survey.

This also applied to the price premium respondents could envisage paying for a more sustainable product. On average, manufacturers could charge 18% more than their competitors if they offered a demonstrably more sustainable product.

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that more than 93% of respondents to the global survey stated that they had a strong or above-average interest in sustainability issues. Even considering that those who took part in the survey were more motivated than people not particularly interested in the topic, that figure is still high. Yet, not everyone found it easy to define what the term sustainability meant to them. Nearly a quarter of the respondents said they were well acquainted with the term, but had difficulty defining it precisely. From the others, we received many definitions and comments in the “free text” section of the survey that showed the broad range of how people understand the issue (see box to the right).

What does sustainability mean? Living in a circular economy modeled on nature, where so-called “waste” becomes a useful input further down the line. It is the term used to have continuity and growth in business, without having a negative impact on stakeholders and the environment. Having the same ecosystem quality after all our human, urban, industrial, technological, political, energy developments. Using resources responsibly, so future generations may live as well as, or better than, us. This applies to every resource used by society. Minimizing the new use of non-renewable materials, maximizing the recycling of all materials, and minimizing energy and water usage. Product lifetimes of at least 10 years. Sustainability and cost-effectiveness In the long run, only sustainable solutions will be cost-effective. You have to evaluate the total cost of ownership and not just purchase prices. Sometimes we need to pay extra for a sustainable energy technology. Our challenge is to include economics in sustainability. We see that renewable energy is now cheaper than fossil fuels, vegetable-based diets reduce health care costs, investment in energy saving is profitable and that reliance on oil causes wars. True sustainability will reduce, rather than increase, the real costs of our world. It is a matter of when and if the true cost – the irreparable damage to the environment – is accounted for. The cost-effective approach to production is often shortsighted and neglects to take the true costs into consideration. It really depends on the scope and definition of costs and sustainability if something is not. If cradle to grave costs are evaluated properly, sustainability is cost-effective.What is sustainability?

Sustainability goals

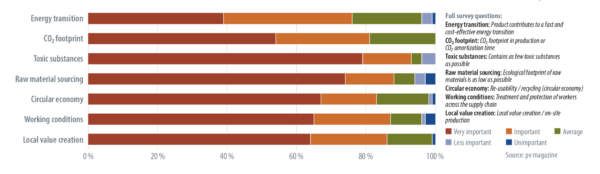

It is often not possible to achieve all sustainability goals all of the time. For instance, under the current political conditions, the energy transition could slow down somewhat if foregoing toxic substances made solar power somewhat more expensive. The question is how these conflicting objectives are reflected in companies’ priorities.

One solution would be to give precedence to the goal of a “quick and inexpensive energy transition.” After all, the public perceives climate change as the most pressing problem because the time for corrective action is quickly running out. So, should the goal of a “quick and inexpensive energy transition” have a higher priority than other sustainability goals? In other words, it is better to install cheap modules quickly, even if you have to accept that they contain toxic substances within certain limits and under certain conditions? In all, on a scale of one to five, 27% of participants agreed with the statement “Energy transition absolutely” – the five point answer – and the mean value was 3.4.

In a direct assessment, this statement received significantly less approval than the alternate statement that the energy transition must be implemented concurrently with all other equal sustainability goals. A total of 58% of the participants agreed with the statement “holistic energy transition,” giving it the highest rating; the average value was 4.2.

Harald Schütt/ pv magazine

Even when evaluating more detailed sustainability goals, the participants hardly differed at all, with very high overall approval values across the board (see chart above). A rapid energy transition was considered just as important for these respondents as the notion that products should contain low amounts of toxic substances, but not more important. There was even a slightly higher level of approval for recyclability. The importance of working conditions in production and local added value, on the other hand, was rated slightly lower by survey participants. The survey focused on Germany painted a similar picture.

One question remained, however: How can you tell that products and their production are sustainable? We asked participants to rate the statement, “The term sustainability is often used by manufacturers as a marketing tool. It often does not mean much, and amounts to little more than greenwashing.” And 75% of the respondents agreed with this statement. Another statement read “sustainability certificates are a way to increase trust.” This was met with an approval rating of 82%. However, one participant noted that with external certifications, who carried them out was also important, as was demonstrated by the criticism of the MSC certification in fishing, which is why mandatory certificates or standards create even more trust. More than half of the participants agreed unconditionally. The average approval rating was 86%. The same picture emerges if one evaluates the survey of all 353 participants (the global survey together with the survey in Germany).

Mixed opinions

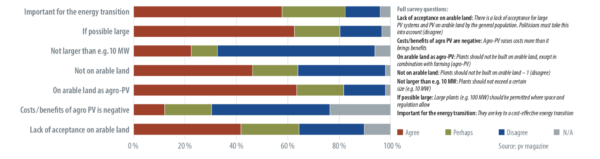

Sustainability concerns both products and how they are used. In some countries, such as the United States, China, Australia and Spain, plants are built with several hundred megawatts of capacity. In other countries, such as Germany, mainly plants under 10 MW are built because larger plants were not eligible for subsidies. In addition, only a very limited number of subsidized solar farms may be built on arable land.

Currently, many municipalities oppose such projects. Now, one could argue that this is naturally due to the fact that in Germany the population density is very high and it has no desert areas suitable for little more than the installation of solar plants. But according to estimates by Fraunhofer ISE, even in Germany no more than 2% of arable land would be needed to add 300 GW of the photovoltaic power necessary for the energy transition. Nevertheless, the discussion about which land may be used for solar, and when, is emotionally charged.

We therefore wanted to figure out how participants saw large-scale plants and agricultural land as potential sites (see chart to the top right). According to the survey, 86% globally and almost 60% in Germany agreed completely or somewhat with the statement that large PV plants are necessary for an inexpensive energy transition. A similar percentage believes that you should build large – around 100 MW – wherever possible.

Harald Schütt/ pv magazine

However, 51% agreed with the statement that solar panels should not be installed on arable land, and just as many understood the acceptance problem and thought it should be taken into account. The answers are not mutually exclusive. There are also non-agricultural areas in Germany – for instance, in former open pit lignite mines. However, it is doubtful whether the solar potential in such areas is sufficient. If systems are built on farmland, 73% agree that they should be implemented as agri-photovoltaic systems in combination with farming. Although many respondents could not estimate the cost of such projects, 51% did not believe that the cost-benefit ratio was negative.

Conflicting goals

We asked somewhat more detailed questions about the toxicity of components in photovoltaic systems. For the participants, preventing the release of toxic substances and the exposure of workers in production was not enough. The goal of replacing toxic substances completely and as far as possible (see chart top left) was met with the same level of approval.

Looking at these and other replies, the respondents to our survey, which should represent a good cross-section of the industry, clearly tend towards the position of environmental organizations, as can be seen in the discussion on lead-free modules. The participants see the conflict goals with the pressure to be economical, and 79% of them stated that, in their opinion, the goals of cost-effectiveness and sustainability are always, often or sometimes mutually exclusive.

The position of not wanting to sacrifice other sustainability goals for a quick and inexpensive energy transition could be reconciled with this under one condition. It requires a desire to achieve all sustainability goals as a society. A consequence of this attitude would be not always to follow the most cost-effective path towards the energy transition. Thus, the discussion becomes inseparable from the discussion about the logic of economic growth. In addition, one participant notes that a cheaper energy transition is not necessarily a faster one. Another respondent comments: “When the overall costs are considered – including all external costs, such as pollution – that are reflected in product prices, profitability and sustainability are not mutually exclusive.” Many other participants express a similar opinion when they write such statements as: “The definition of cost-effectiveness changes depending on the time horizon under consideration.”

From the survey to reporting

In terms of journalistic reporting, 73% of participants wanted to see coverage of recycling. In second place, at 66%, was the topic of “solutions for CO2 reduction.” In addition, 63% wanted reporting on corporate sustainability strategies. Avoidance of toxic substances is a topic that 55% wanted to see addressed. Accordingly, we reported on the question of whether modules should be lead-free in the future (see p.60-63). The conditions under which raw materials are extracted were also mentioned as a desired topic. This will be addressed in the next quarterly focus of the UP initiative. We have also received many other suggestions for which we would like to thank our readers, and which we will consider for future editions.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

I love the optimism of this piece, but from my experience, most corporate execs are only looking at ROI, although they are tuned enough to the staggering cost reductions in renewables, they want to “wait it” out. There still isn’t enough of a push from the investment community to hold corporations feet to the fire – they are losing out on positioning themselves for a great energy transition. They should all be committing themselves to modest 5% renewable targets within 2 years, learning and doing preferred partnering, driving up performance and returns of the next 10% commitment, etc. This can and should go much further and faster than timed current CEOs have appetite for.

PV system, why cannot use simple roof metal sheet to it work.