An international group of scientists have hypothesized that renewables-powered heat pumps could potentially be one of the fastest ways to reduce Germany’s imports of Russian gas. To test the hypothesis, they investigated whether more gas can be substituted by replacing gas boilers with renewables-powered heat pumps. They also considered the use of renewable electricity to reduce the load hours of existing gas-fired power plants.

The investigation rests on a comparison of the coefficient of performance (COP) for heat pumps with the efficiency of gas-fired power stations. The COP is defined as the amount of heat moved by the heat pump, divided by the electric power required to operate it. The scientists used the efficiency of combined cycle gas turbines (CCGT) as a reference, as they provide the bulk of gas-based electricity in Germany.

“Their average annual efficiency in 2020 is the ratio between their electricity generation, which was 95.0 TWh, and the gas consumed, which was 171.4 TWh, yielding 55%,” they said. “To account for grid losses, we lower this value to 50%.”

They assumed a COP of 2 for industrial heat pumps used in the chemical, paper, and processing industries. For residential space heating, they took the COP for a “commonly sold” air-to-water heat pump: the GMLW 14 PLUS from German heating equipment manufacturer Ochsner. Its COP varies between 3.4 and 5.3 to heat water to 35 C. To heat water to 50 C and 60 C, the COP is 3.1 and 2.8, respectively, according to the product’s datasheet. The academics assumed an average COP of 2.5 for warm water.

They modeled the German electricity system using hourly generation data of all contributing power plants, wind farms, decentralized PV, and storage capacities in 2020 – the reference year. To model near-future power generation, they included additions to PV and onshore and offshore wind, according to the plants of the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection. They assumed that Germany would undertake sufficient grid expansion to manage these capacity additions.

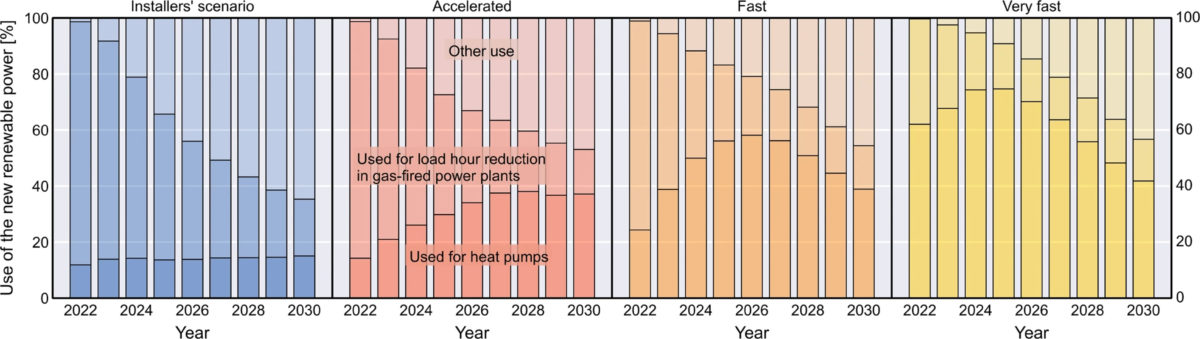

The model features four scenarios: a “business-as-usual installer’s roadmap” scenario, an “accelerated” scenario, and “fast” and “very fast” scenarios. The results show that between 2022 and 2024, new solar and wind capacity mostly reduces the load hours of gas-fired power plants.

“Our hourly resolved modeling shows that this is because in these first years, there are many hours when the sun is shining and/or the wind is blowing, but not enough wind farms and PV capacities are installed to cover grid demand entirely,” said the researchers.

However, in the “fast” and “very fast” scenarios, heat pumps draw most of the newly added renewable power from 2024 to 2030. They represent the fastest way to reduce gas imports in Germany, according to the scientists.

The “very fast” scenario shows gas savings of about 30% by 2025. That is the equivalent of 290 TWh or 28 billion cubic meters, given that Germany imported 971 TWh of gas in 2020.

“Considering that in 2020, about 50% of the gas was imported from the Russian Federation, the very fast scenario can save about 60% of this gas by 2025,” they argued.

The “fast,” “accelerated,” and “installers’ roadmap” scenarios achieve total gas savings of about 22%, 18%, and 15% by 2025, respectively.

“The scenarios, developed here for Germany, must accordingly be adjusted to specifics in other countries, but offer clear, tangible, pathways to reduce the price volatility and supply risks of fossil gas,” the scientists concluded.

They shared their findings in “Replacing gas boilers with heat pumps is the fastest way to cut German gas consumption,” recently published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

I will start with a declaration: I am a power systems engineer, who used to design, build and operate electrical distribution networks. Thus, I have a very good understanding of what such networks can & cannot support. Most distribution networks were not designed to support heat (exception: parts of the french network – where thermal storage – is/was a feature). Anyway, I’m not doubting any of the data in the scientists paper. But they don’t ask the question: can German electricity distribution networks support a large-scale roll out of HPs. No they can’t. I & others spent 2 man years analysing the problem (HPs, EVs, PV) and most LV distribution networks run out of capacity once 20 – 25% HP penetration is reached – sooner if EVs start to take off. Given most LV cables are direct-lay, there are not easy answers to LV network reinforcement. So yes HPs could de-carb German space heat – but only in combo with fuel cells.