With work already underway on a test cavern for hydrogen storage from German energy provider EWE, as well as Dutch gas giant Gasunie beginning storage of hydrogen at its underground facility in Zuidwending, and geologically resourceful countries such as Canada estimating huge potential for large scale seasonal underground hydrogen storage (UHS), it is no surprise that resource-rich Australia is also eyeing up the “massive opportunity” for UHS, which is being pointed to by many as a feasible solution that could foster true growth for the hydrogen economy.

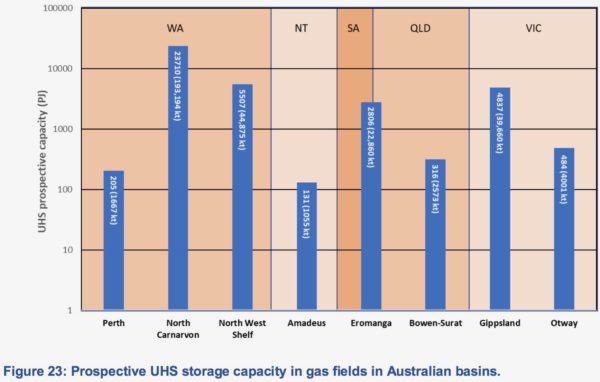

Research from Future Fuels Cooperative Research Centre (FFCRC), an industry focussed research, development and demonstration partnership, has mapped Australia's UHS capacity at potentially 310 million tons (38,000 PJ), a figure approximately 60 times larger than what a developed domestic and export Australian hydrogen industry would need, which FFCRC estimates at around five million tonnes (600 PJ).

The research was led by Jonathan Ennis-King, leading reservoir simulation researcher at Australia's National Science Agency, the CSIRO, with the CSIRO's Hydrogen Industry Mission.

FFCRC pulls that figure from research mapping potential sites suitable for UHS, such as salt caverns (created by circulation of freshwater), depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs, aquifers and engineered caverns. Of course, each rock formation has its own advantages and disadvantages, but once the scale of storage at a site exceeds the tens of tons, says FFCRC, “UHS is the cheapest and safest large-scale storage option for industrial-sized purposes.”

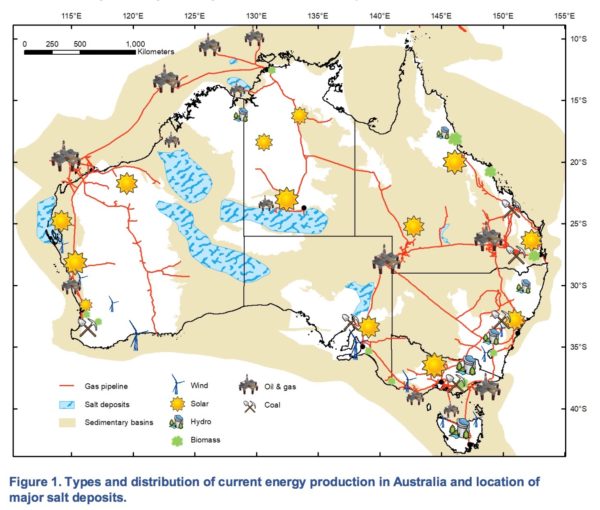

Salt caverns are an established hydrogen storage technology already, although Australia's sedimentary basins where potential salt deposits may be suitable for the creation of large storage caverns are not proximate to locations touted for large-scale hydrogen production. However, there are some interesting options. The report places the most likely locations as the north-western part of the Canning Basin, near to renewable energy resources on the North West Shelf, the Adavale Basin in western Queensland, and the Amadeus Basin in the Northern Territory.

However, the most promising storage options for UHS in Australia might just be depleted gas fields, though it is not clear whether stored hydrogen and residual hydrocarbons would play nicely together. Although the re-use of depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs would be far cheaper than developing UHS-specific salt caverns. But long-term storage operating costs of such a site “may only constitute a small fraction of the total cost of storage”.

Of course, what needs to be stressed is that potential UHS sites would need to be assessed on a site-by-site basis. And the same goes for any purpose-built or re-purposed UHS infrastructure, still a very nascent technology, but with the potential to be implemented in close proximity to renewable resources.

Popular content

Cost is also highly dependent on site-by-site analysis, however the report does provide a helpful table:

Ultimately, the report posits “The cost of UHS may only constitute a comparatively small fraction of the whole hydrogen value chain.”

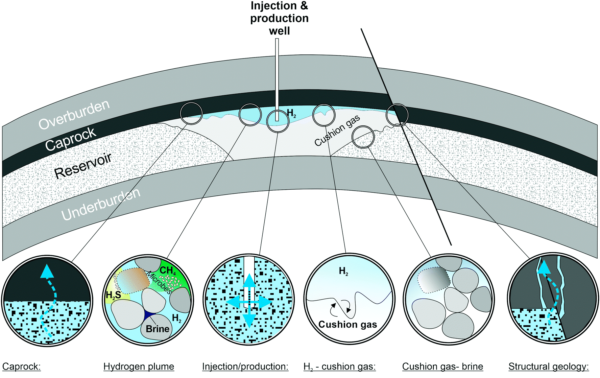

Challenges to UHS

There are, however, numerous challenges to UHS, including the fluid flow behaviour of hydrogen in subsurface reservoirs, geochemical reactions caused by the injection of hydrogen, biotic reactions caused by excess hydrogen and the geomechanical response of the subsurface itself to hydrogen storage.

Image: Centre for Geosciences Potsdam

Indeed, in a study titled “Enabling large-scale hydrogen storage in porous media – the scientific challenges“, published in Energy & Environmental Science, European scientists part of the GEO 8 association of European geoscientific research organizations, stressed that there is still an enormous amount of study which needs to be done before UHS can be performed safely and efficiently.

Natural analogues

The FFCRC also points to the promising study of natural analogues, which is to say, natural occurrences of UHS, such as hydrothermal fluids and hydrogen-rich gas at Lidy Hot Spring, Idaho, and Kansas respectively. Further examples are to be found under the Central Indian Ocean Ridge and in the hydrogen-rich gas seep at Chimaera in Turkey. These sites are pointed to as “evidence for the ability of seals to retain hydrogen for significant time periods.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.