From pv magazine 06/2020

From a processor or end-user perspective it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to have a view along the supply chain and know where the materials that enter battery supply chains are coming from or going to. The impacts that the sourcing, processing and manufacture of the aforementioned products have had on their environmental, humanitarian, and social footprints has been practically impossible to ascertain.

Having a view all along the supply chain is the key to understanding these impacts and to be able to comply with regulatory and stakeholder standards. With emerging technologies such as blockchain achieving commercial implementation in certain applications, the necessary visibility in the provenance of materials in supply chains can be transformed.

Raw material sourcing

In Q1 2020, pv magazine's UP sustainability initiative looked at raw material sourcing in batteries. Check out the content here:

Blockchain uses

As we move beyond the initial hype of blockchain and into the phase of practical implementation we see true use cases for its benefits. One of these use cases is in supply chains. Asset management through the full end to end trade life cycle is a challenge. Various actors take part in physical supply chains, all keep their own records and this tends to create inefficiencies and security issues. By applying blockchain technologies, all records can be stored in a single source of truth and errors are reduced, corruption risks mitigated, and business processes simplified. The need for intermediaries is reduced, further minimizing risks and bringing down transaction costs.

Traceability in supply chains has become a focus in investor and stakeholder expectations around responsible sourcing. Industry participants are now faced with the task of embracing digital transformation or getting left behind.

Product provenance

Arguably one of the biggest success stories of using blockchain for the provenance of minerals is in the diamond industry with a system known as Tracr. De Beers, which is one of the biggest players in the diamond industry (until the 1980s, it had a controlling share of the market), established Tracr as a standalone entity.

Once a diamond is mined a digital version is created and traced from its origin at the mine to the end customer. A diamond in a jewelry store on Hatton Street in London has its own digital version on the blockchain, with its full journey from a once rough, uncut stone of significantly less value to a round brilliant gem – the finished product.

Diamonds are, of course, relatively easy to trace, as a rough stone will generally produce only two cut refined diamonds. The metals which are used in batteries change state more often than diamonds and are traded in much larger quantities. The logic, however, remains the same.

Interdependent documents

A public blockchain is available to everyone and often concerns are raised regarding data security and privacy. This challenge is managed through the concept of secure one-way hashes. Every document generates its own identifying has value, which is made publicly available. The hash is of little to no value to an external human viewer, but an auditor that possesses the original document can verify that the hash is genuine. The purpose of the hash is to allow for private documents to be publicly verified.

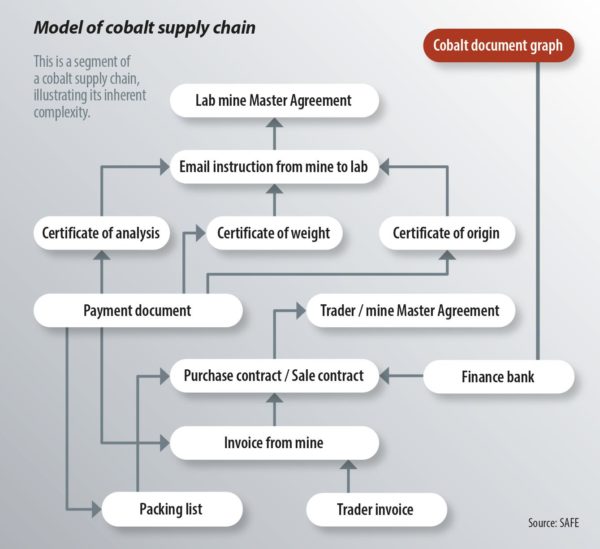

The document flow in a battery material supply chain is complex, as many documents have dependencies on the proper completion of other documents along the chain. Blockchain is the perfect environment in which to manage such a complex document flow, as all relationships between the documents are also publicly verifiable. If a document is missing, incomplete or corrupted, then it is immediately known and the following step cannot be completed.

Popular content

Moving materials through countries, warehouses, ports and processors creates a large number of interdependent documents. Manual interactions with documentation means the risk of errors or corruption is ever present. If each transaction is instantaneously stored on a blockchain, then errors are immediately visible and document tampering becomes virtually impossible.

Compliance, audits, rules

By applying blockchain technologies to supply chains, any stakeholder that needs visibility into the processes and documents in any given supply chain can be given immediate, standardized and incorruptible access to the truth of the life cycle of any materials. This reduces the overhead required to ensure compliance and mitigates the risks of poor disclosure.

Blockchain enables compliance by design, meaning any regulator and client can carry on with everyday business knowing that the necessary standards are being adhered to.

Spillover benefits

A raw material producer and a manufacturer are very far away from each other along the supply chain and often do not know that they are in the same chain at all. A blockchain-enabled supply chain opens a window into all the actions and actors performing functions, visibly linked. New relationships and even partnership opportunities become possible.

Digital transformation is a journey. What companies need to do is begin that journey in the right part of their business. By applying blockchain in supply chains, it digitizes the underlying physical business, which is at the core of the industry. With the digital footprint of their business in hand, companies are ready to take advantage of other technological advancements that become available. The Internet of Things, GPS and other emerging technologies have the potential to further improve efficiency, process optimization, and transparency.

Transparency target

At the end of the day, transparency equals trust, and this is the most important and core function of introducing blockchain into the battery materials supply chain. This on its own is reason enough for investing in blockchain solutions. The metal supply chain industry is working with technology that is severely outdated and in need of the kind of digital disruption that blockchain provides.

About the author

Alex Preston has 15 years of experience delivering solutions to customers via tech transformation. He is now based in London but has also worked in the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Middle East, He specializes in using IT, software and process-automation solutions to achieve business objectives. He has worked for different companies across a range of teams, products and applications.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

3 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.